Enjoy our themed galleries below – all taken from the brilliant Swindon Collection of Modern British Art, held at Swindon Museum and Art Gallery. To find out more about these artworks, try our handy 10 minute Art Snap podcasts, or our family Art Burst resources.

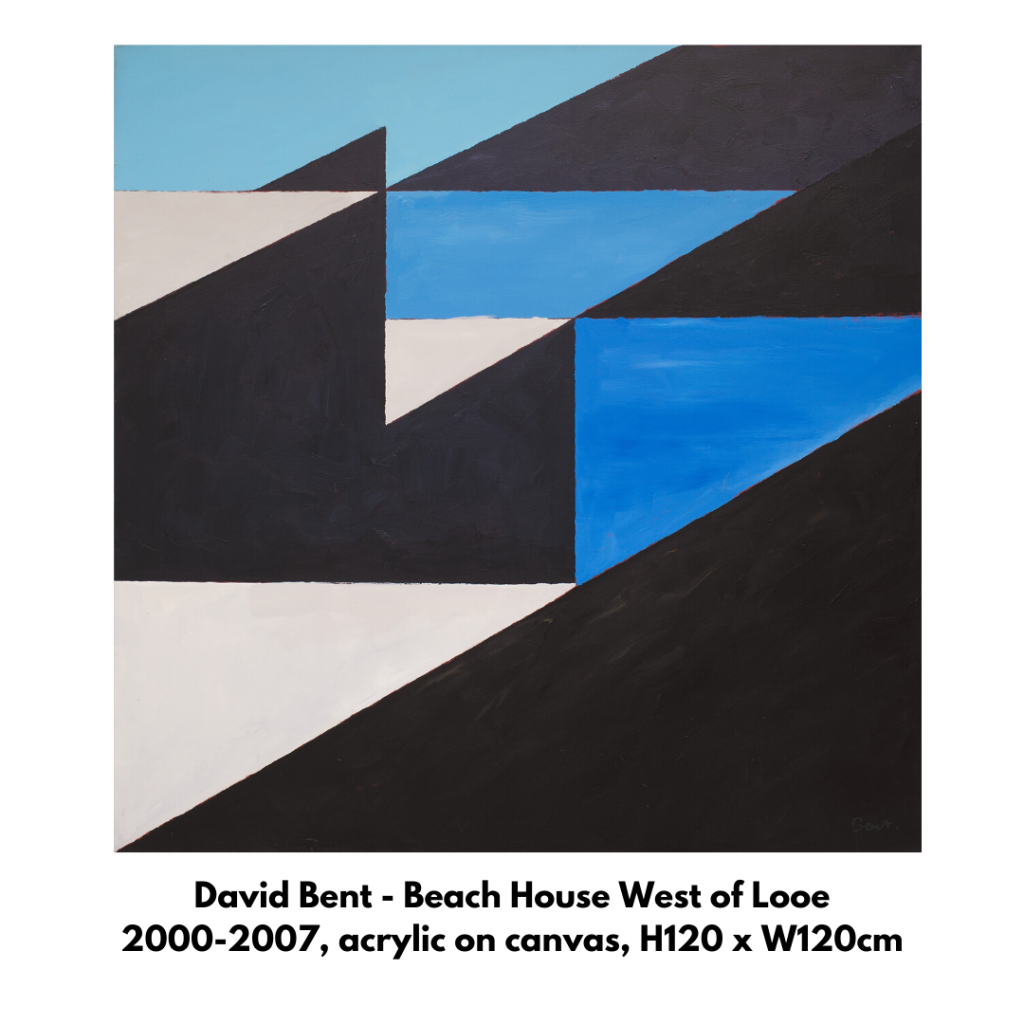

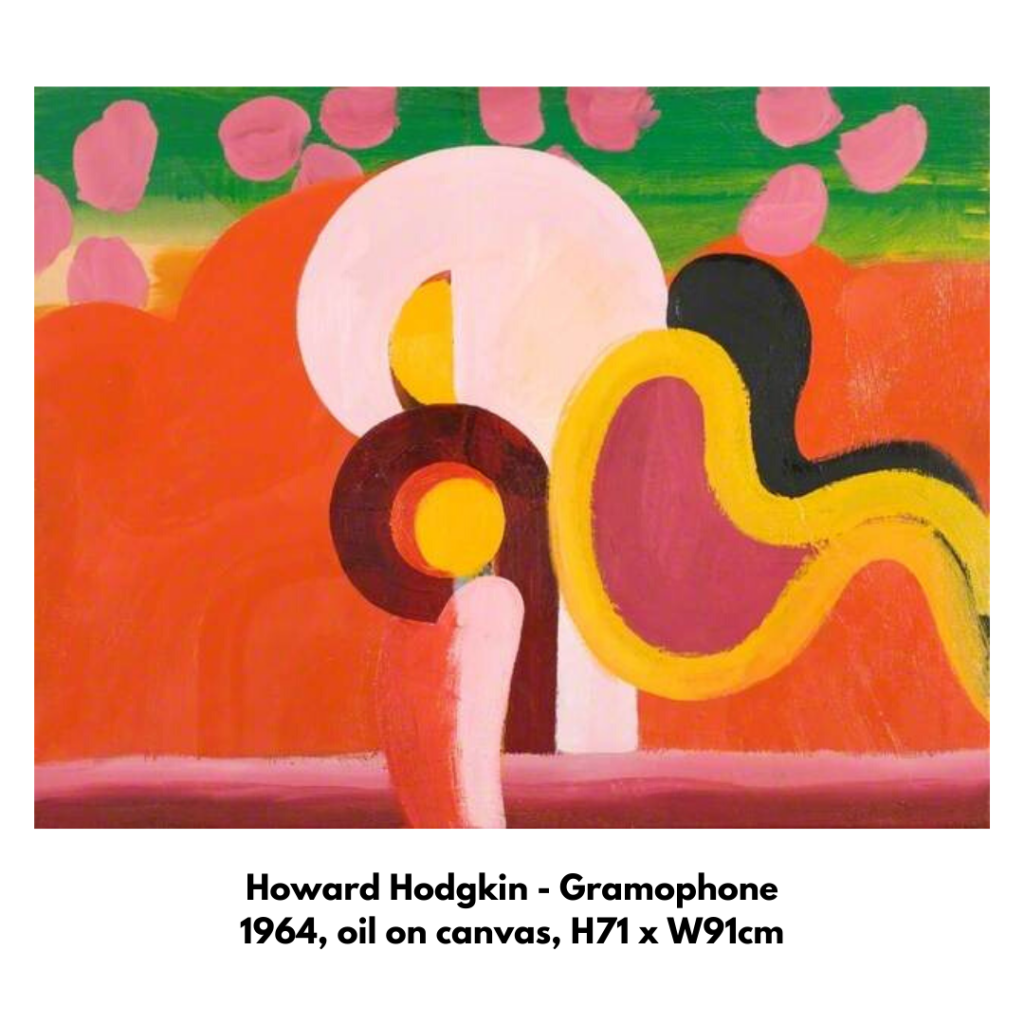

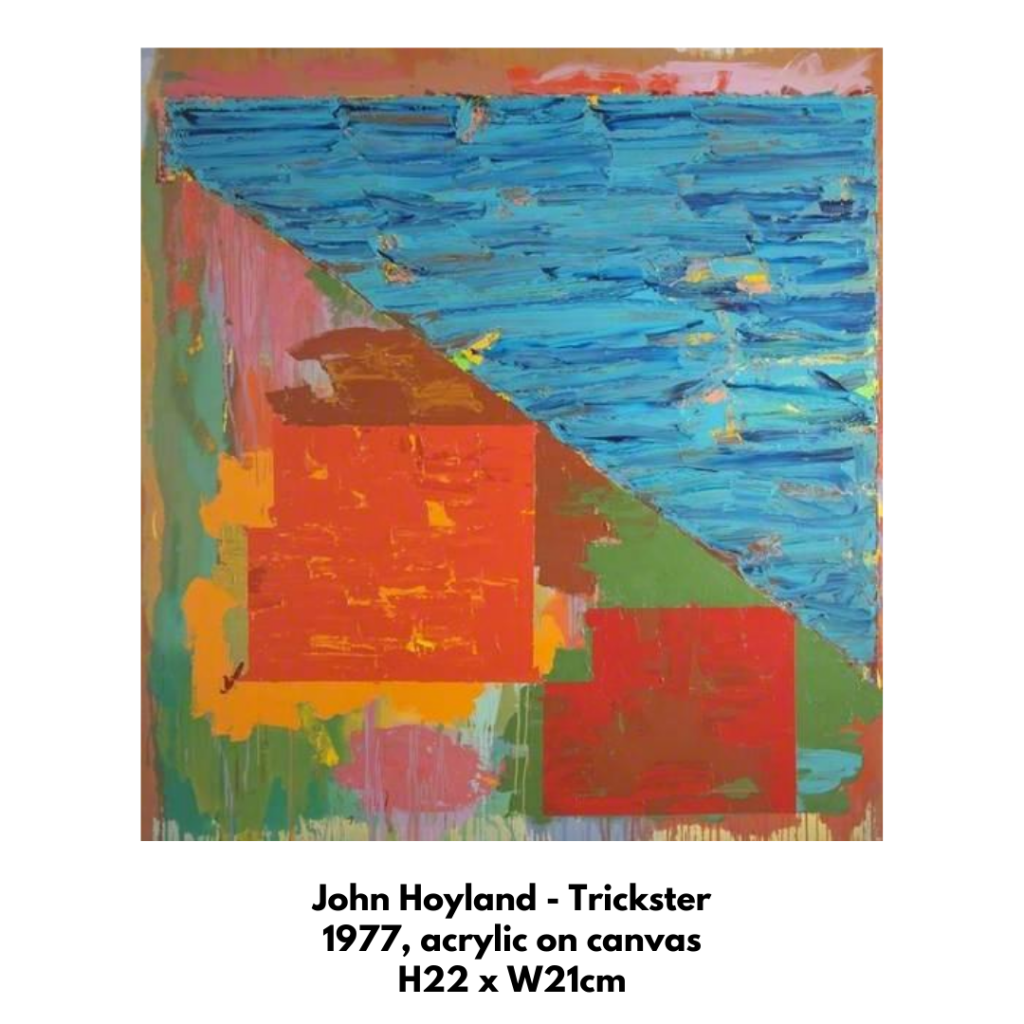

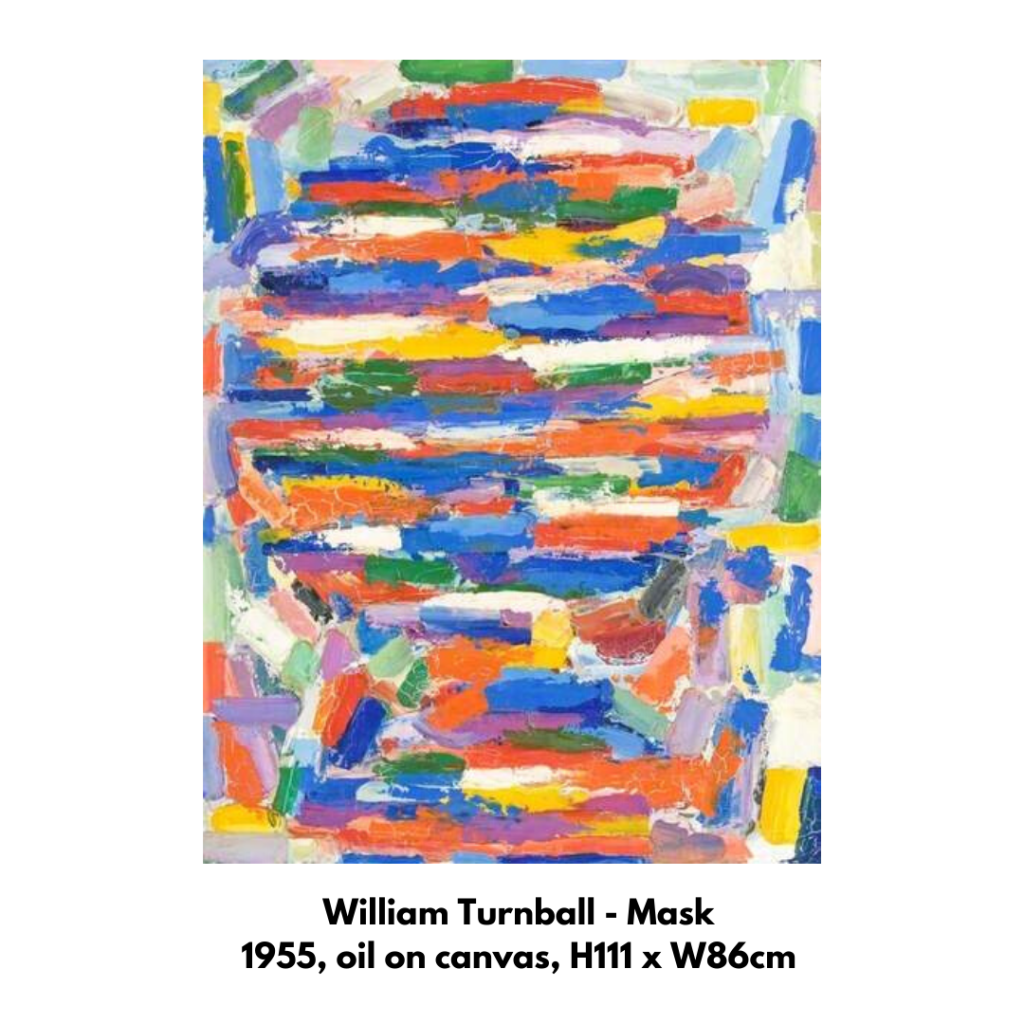

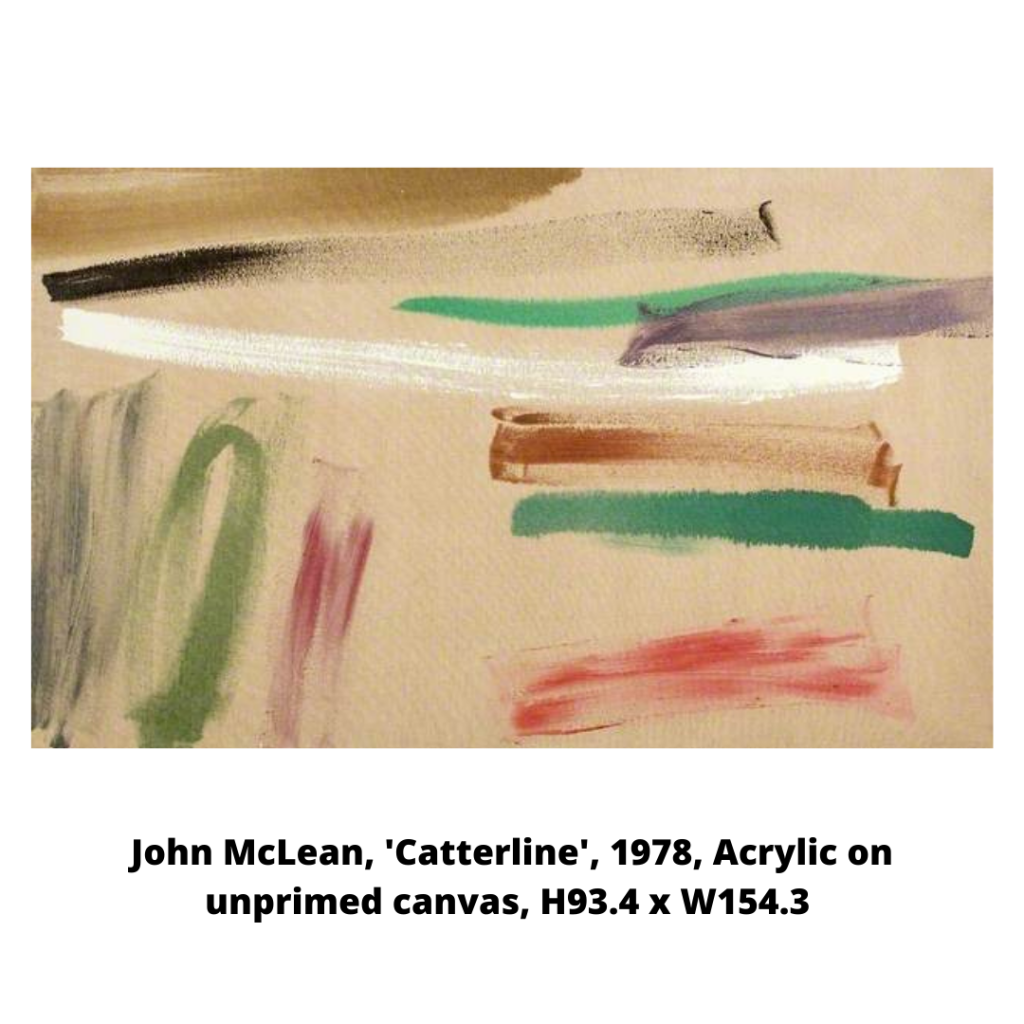

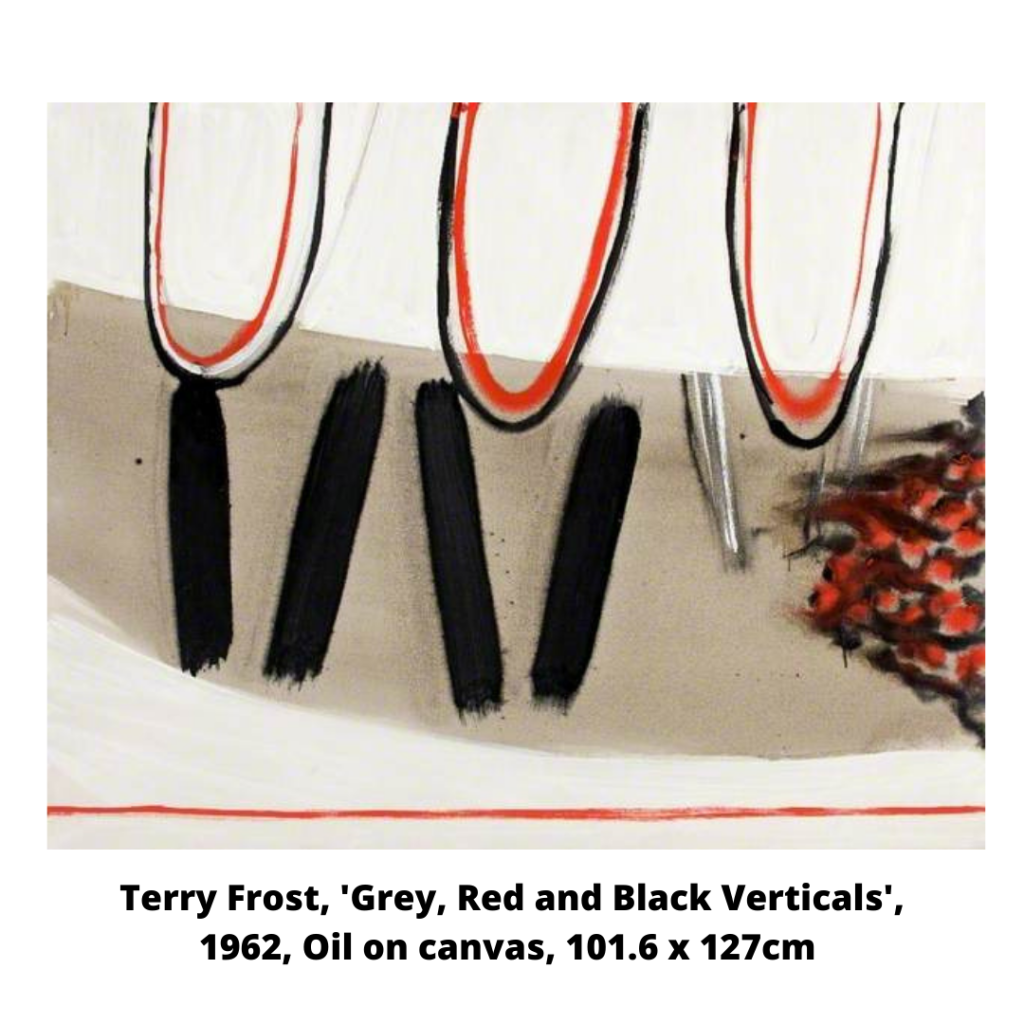

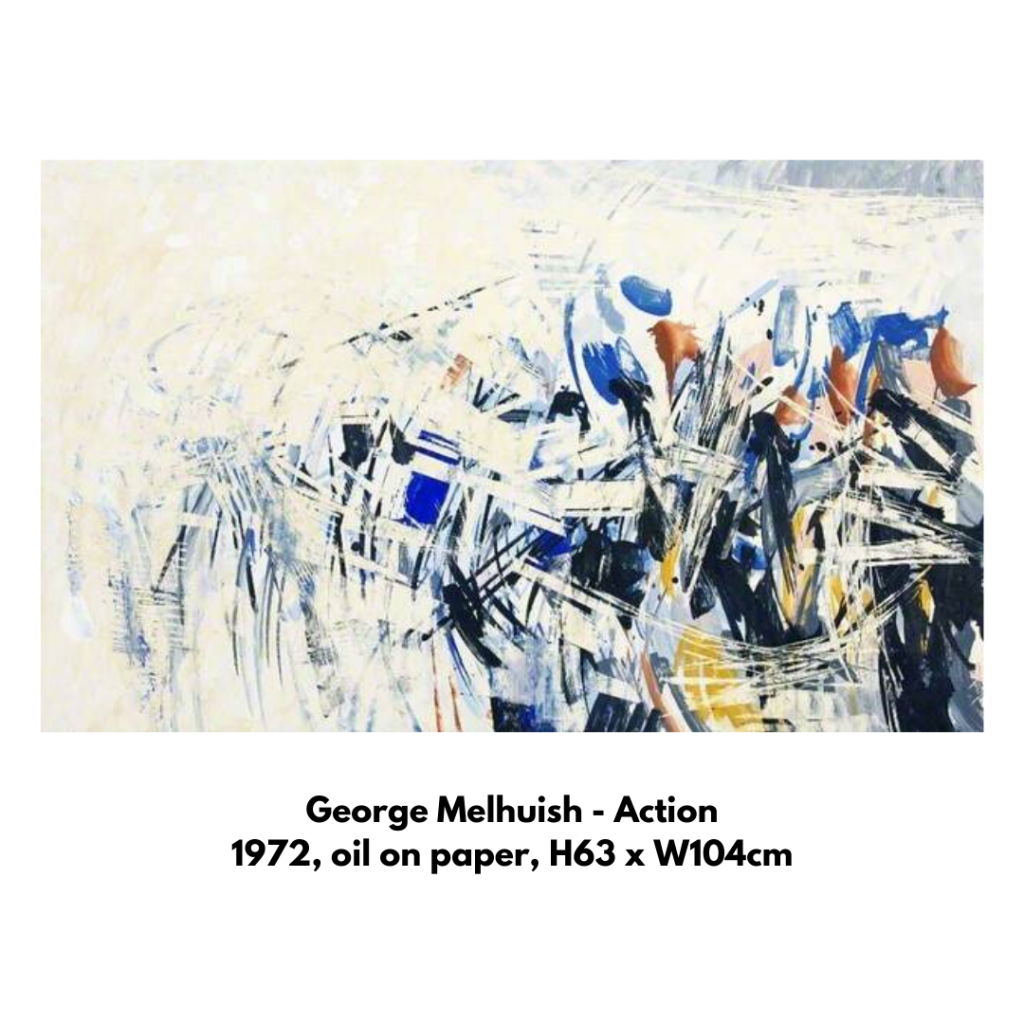

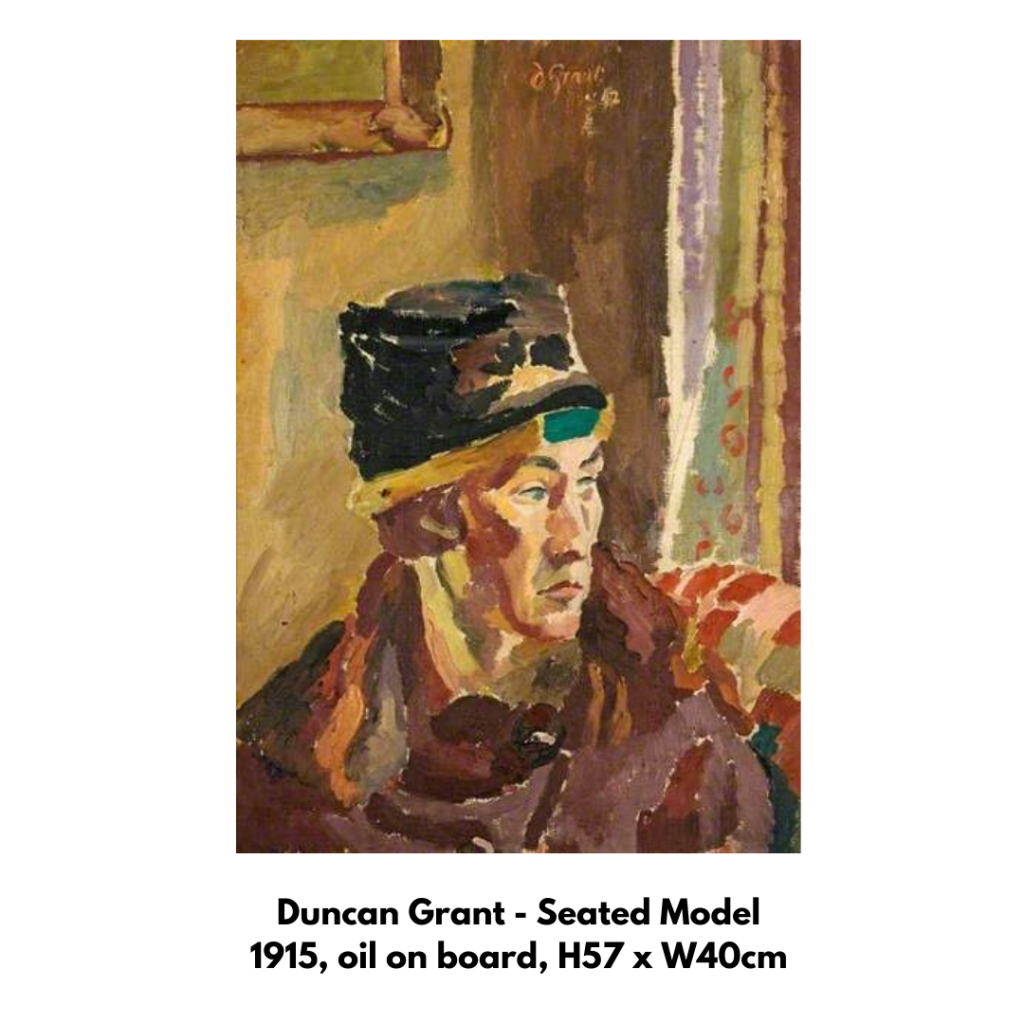

ABSTRACT ART:

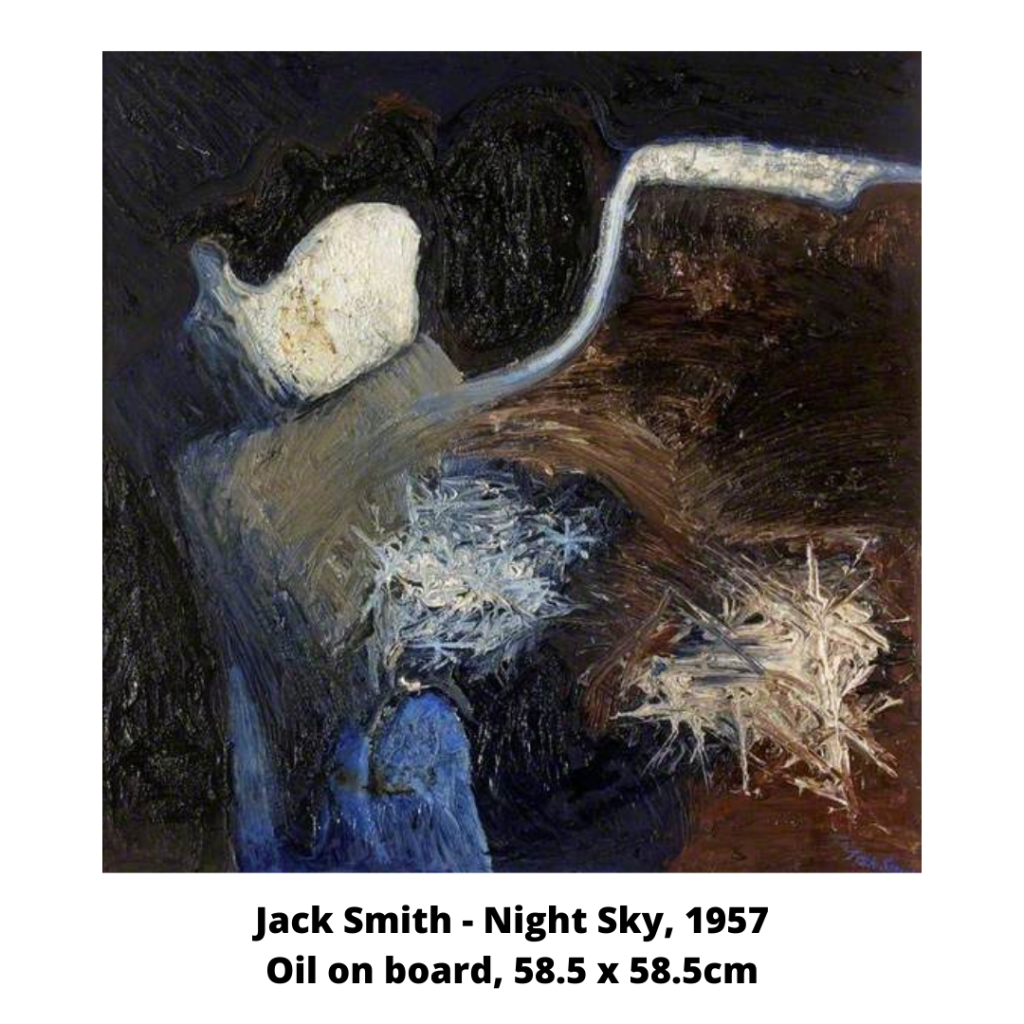

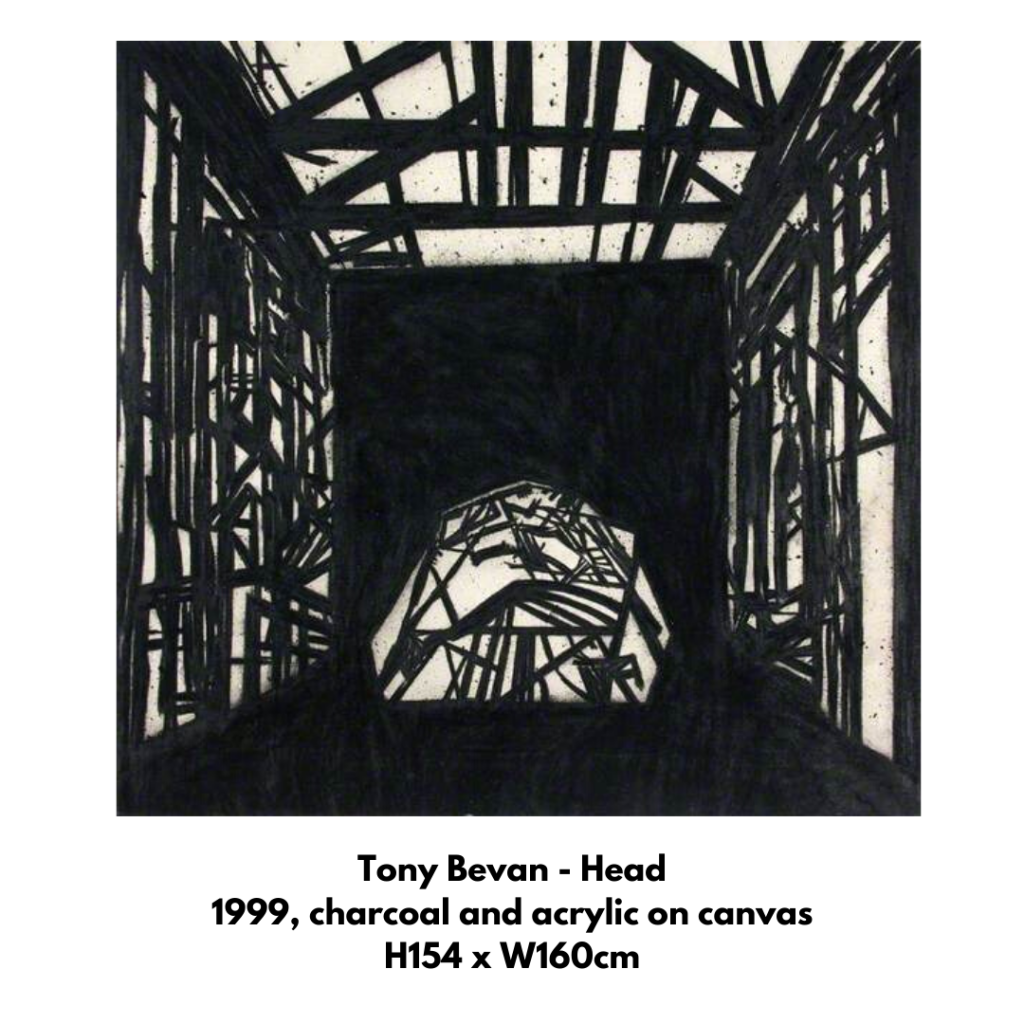

Throughout history, artists have responded to the time they live in, creating images which reflect religious, social, political or personal experiences, and leaving us a rich and varied visual history. The one thing that the majority of art from the 15th – 19th centuries has in common, is a sense of illusionistic space, and clear reference to the world surrounding it. However, the twentieth century was an unprecedented time of change in art. Photography had become a popular way of replicating the world, so artists needed to find a different means of visual communication; one which reflected the search for progress that came with a new modern era.

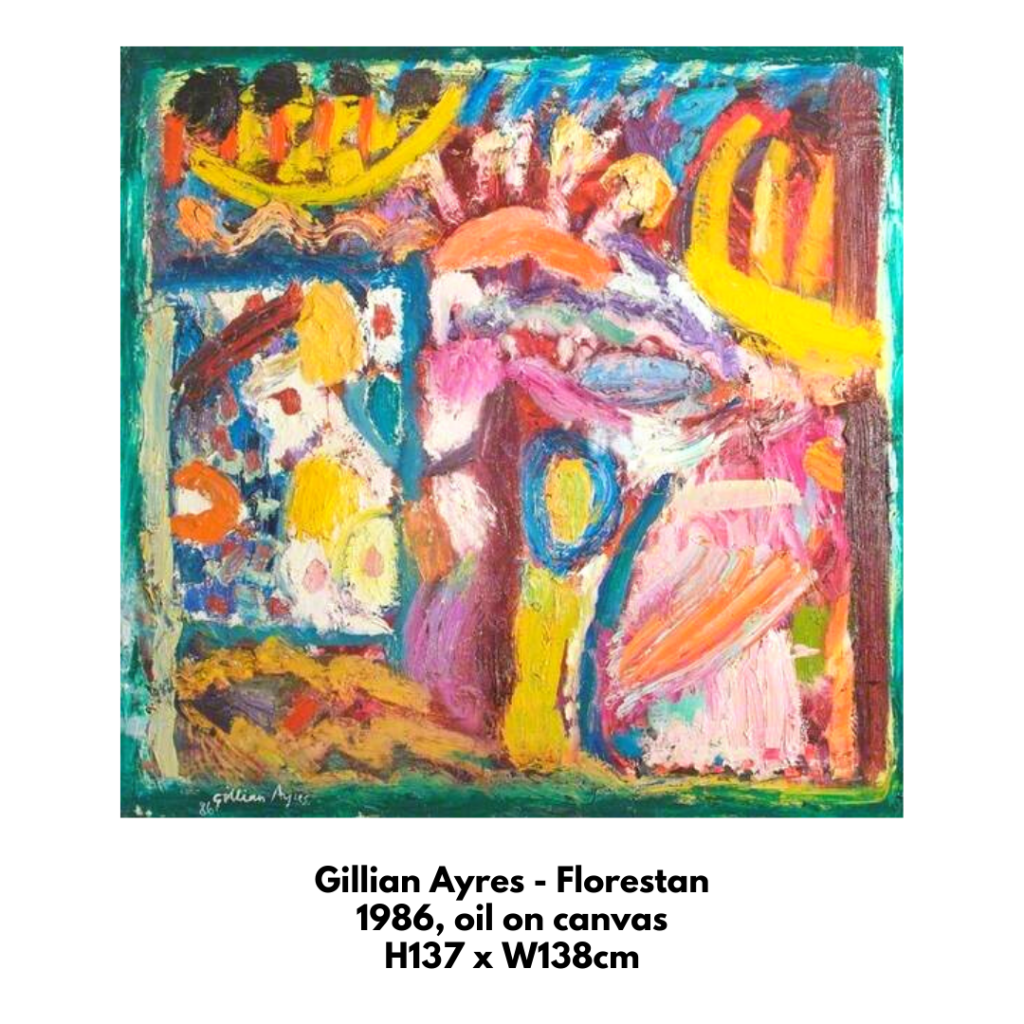

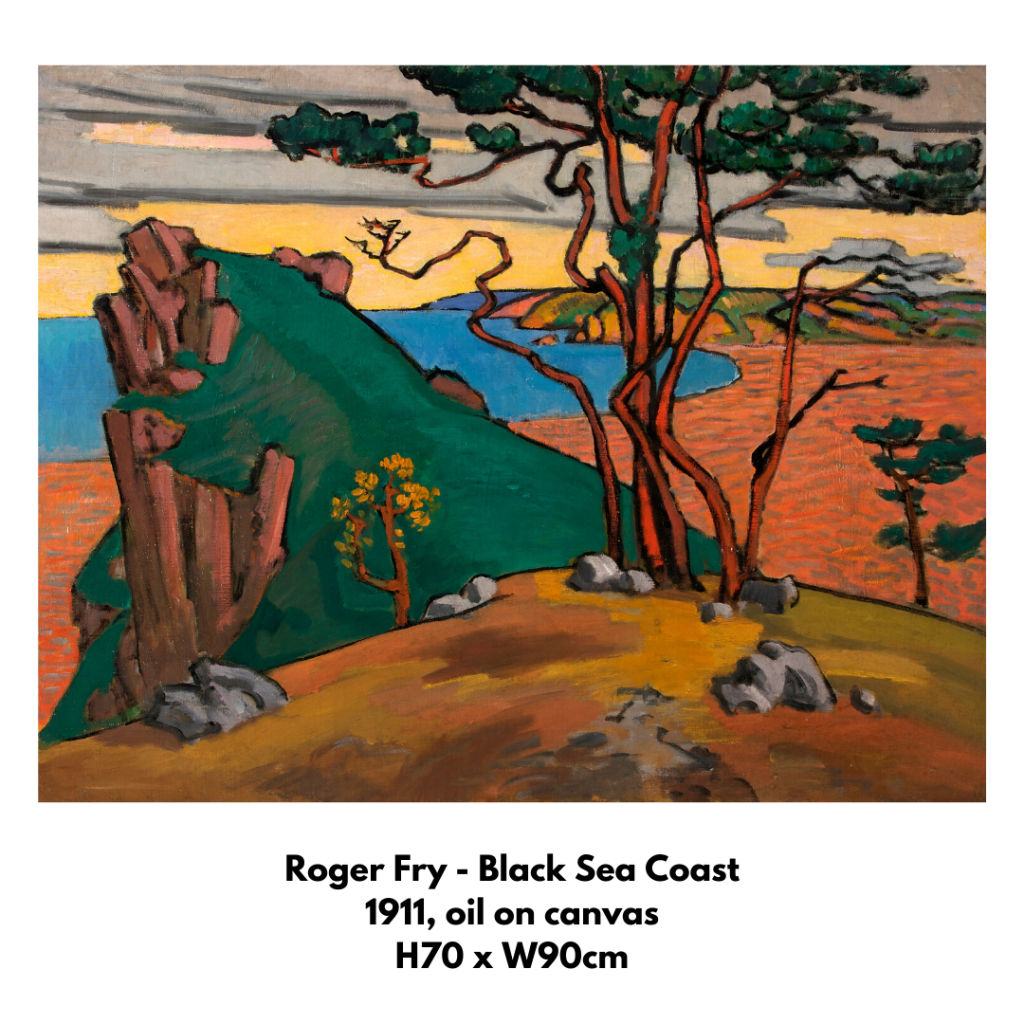

In a nutshell, abstract art is characterised by simplified formal elements such as shape, line and colour. Sometimes subject matter is reduced to certain visually impactful characteristics. At other times, artists focus on a more instinctual approach, responding to personal feelings or memories. Either way, abstract imagery tends to be bold, unexpected and sometimes… a little bit baffling… In Britain, early manifestations of abstract art appeared in work by the Bloomsbury Group and the Vorticists. From there it took many twists and turns, with the likes of Ben Nicholson, Roger Hilton and Gillian Ayres taking bold steps to push visual imagery out of the realms of representation.

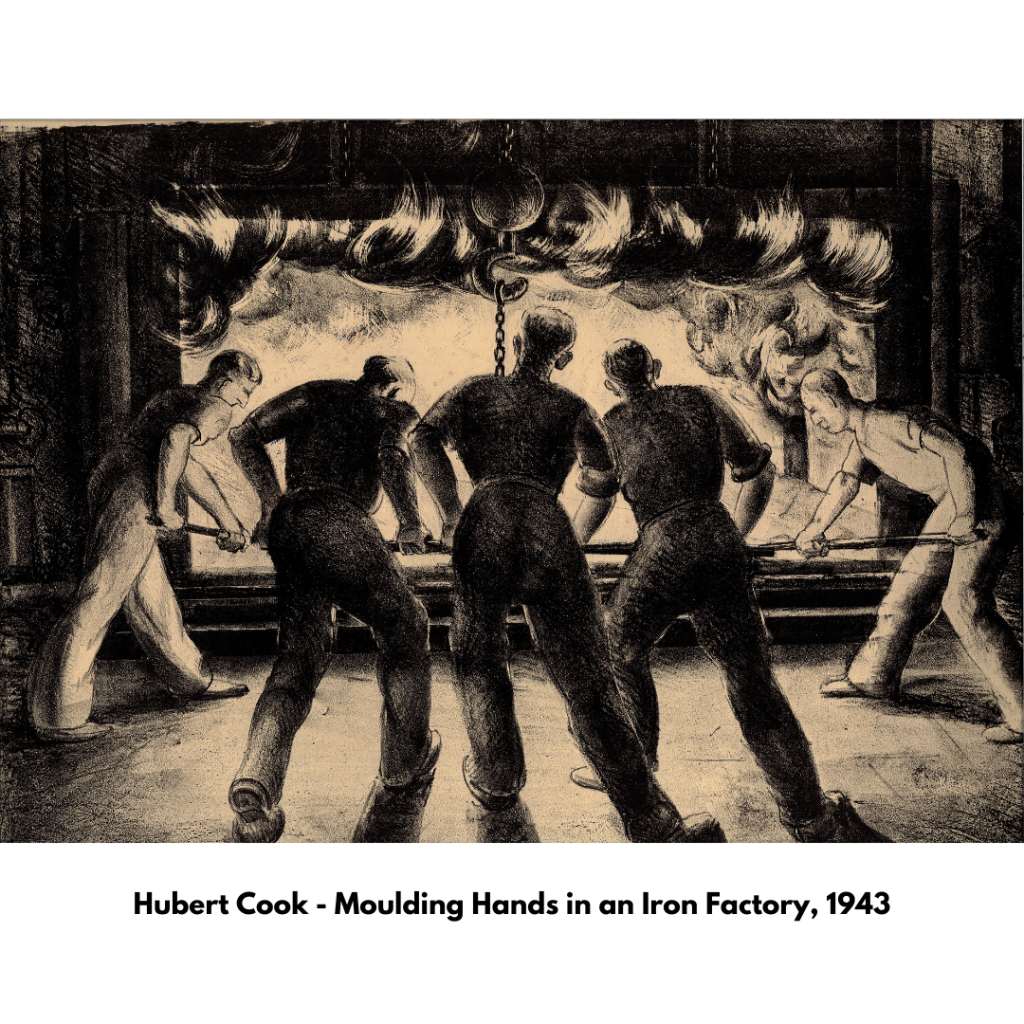

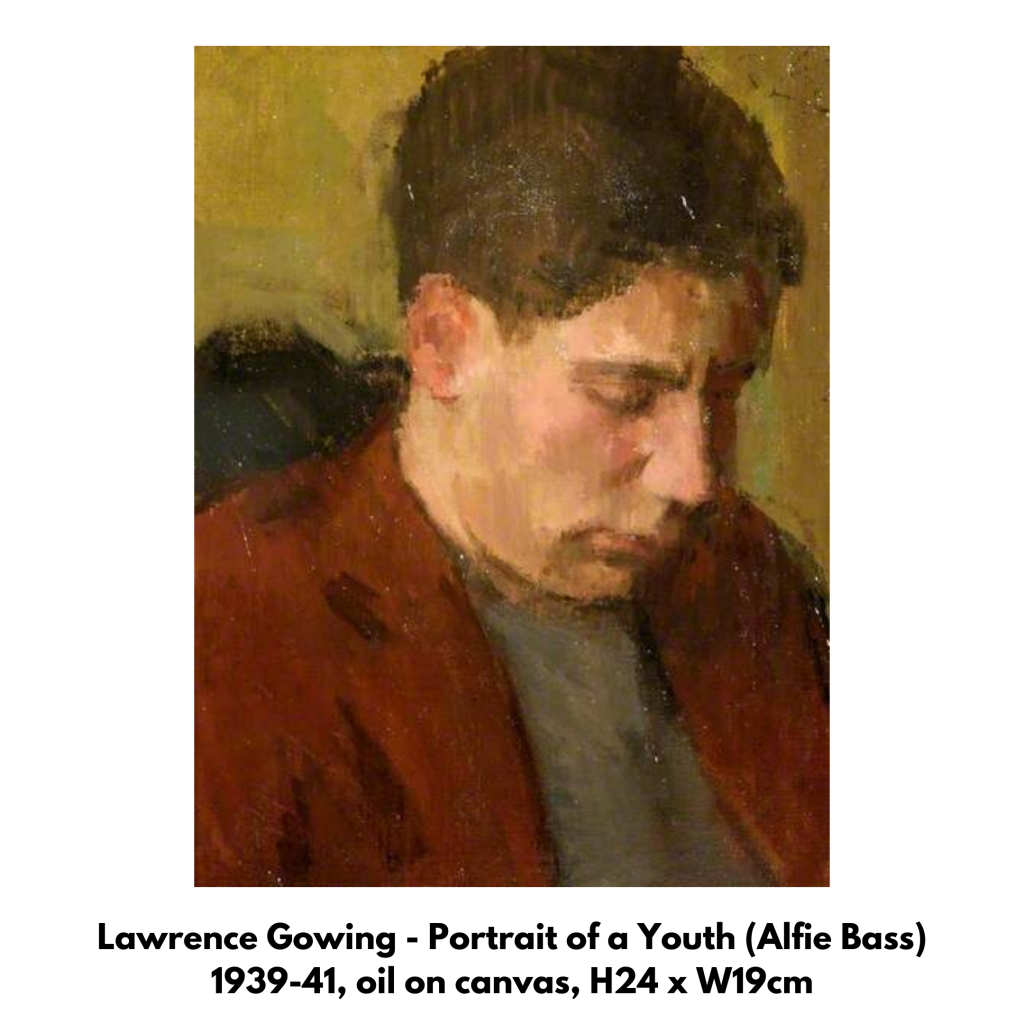

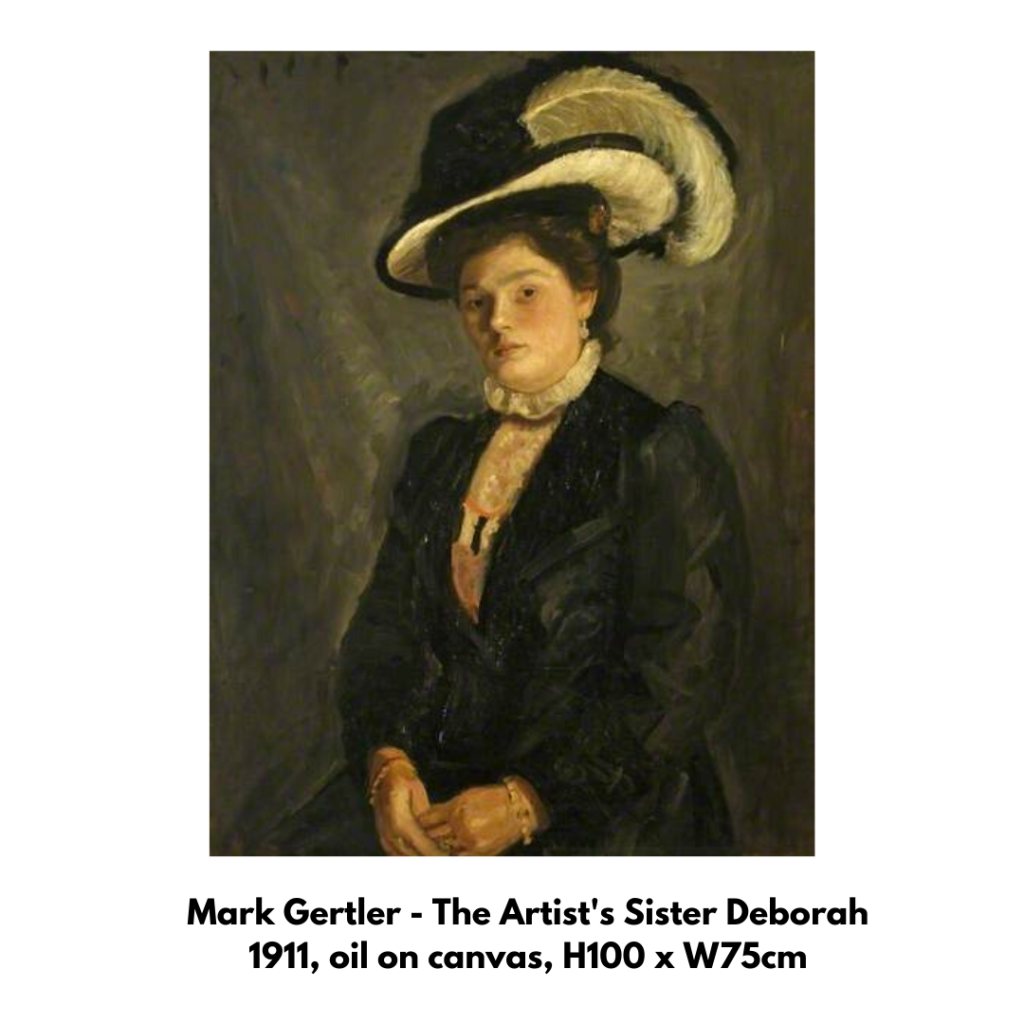

REALISM:

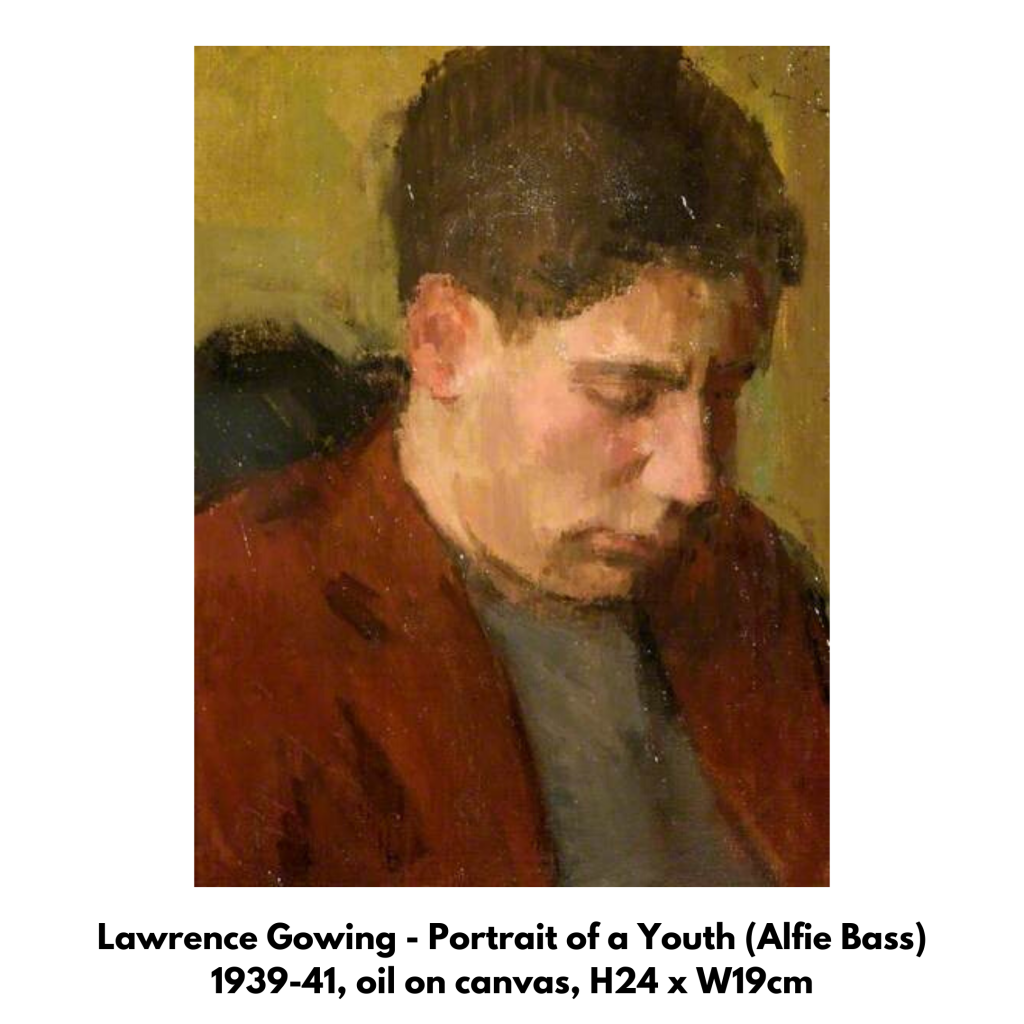

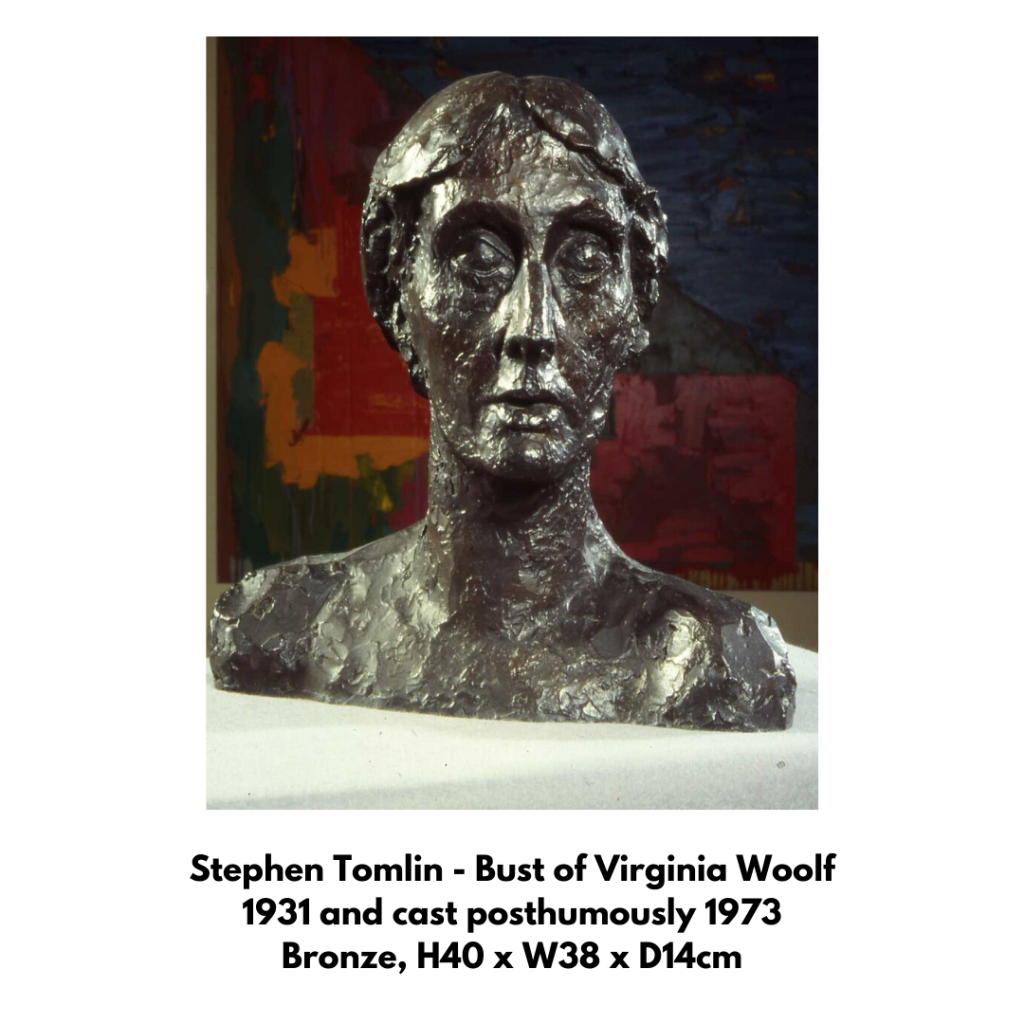

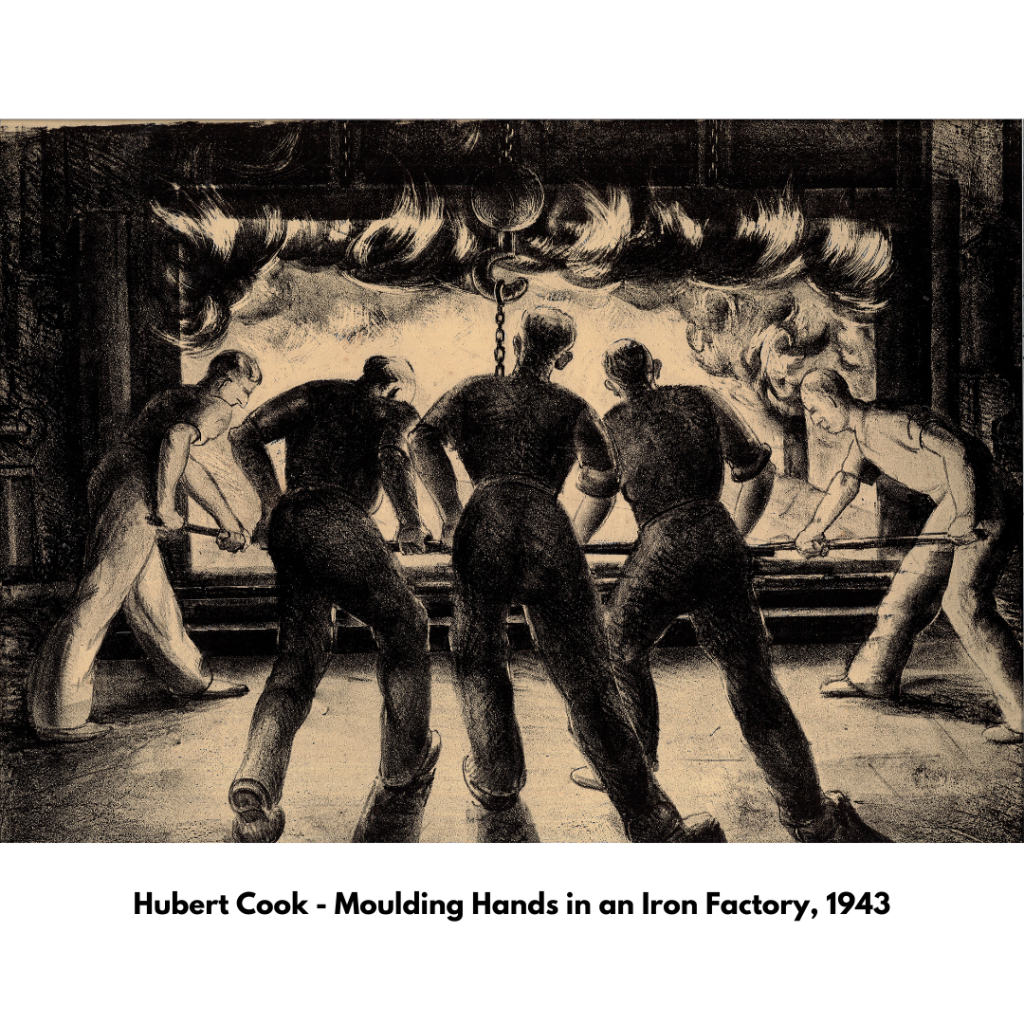

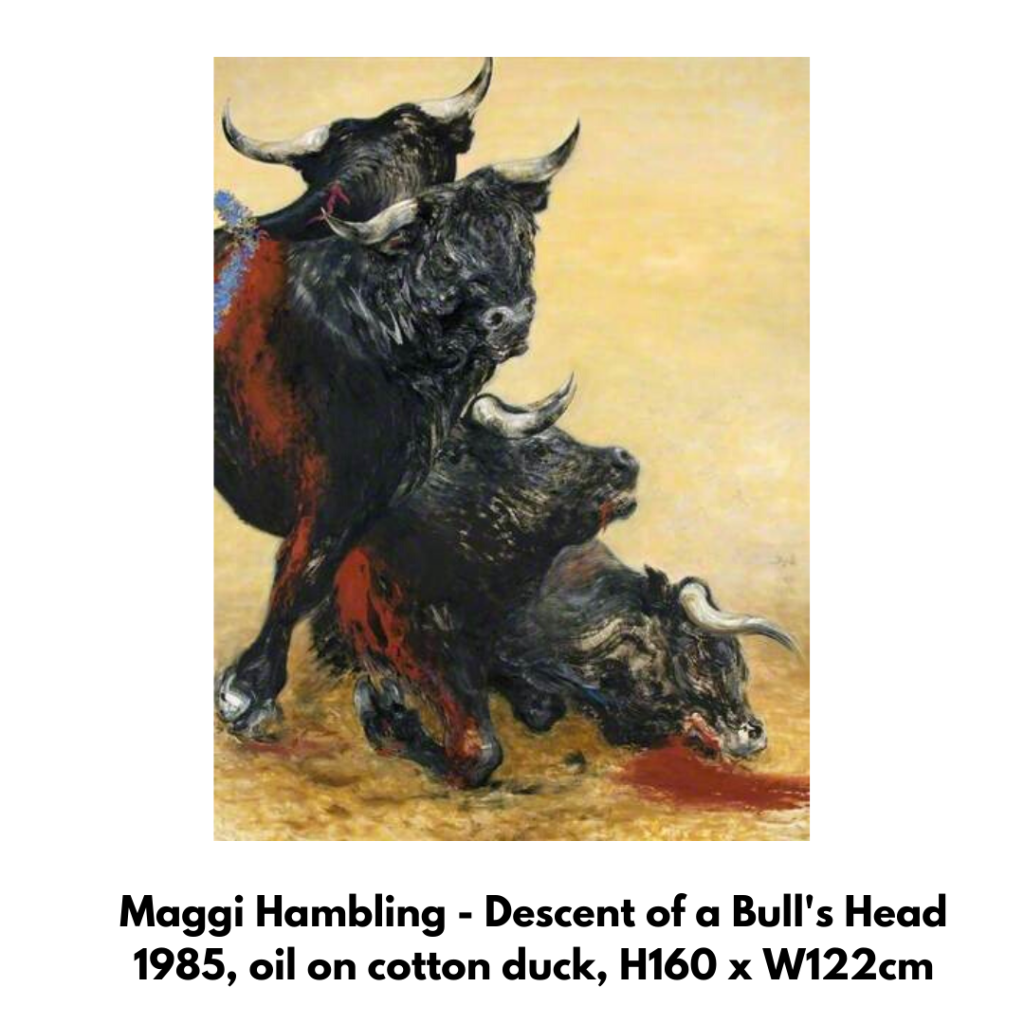

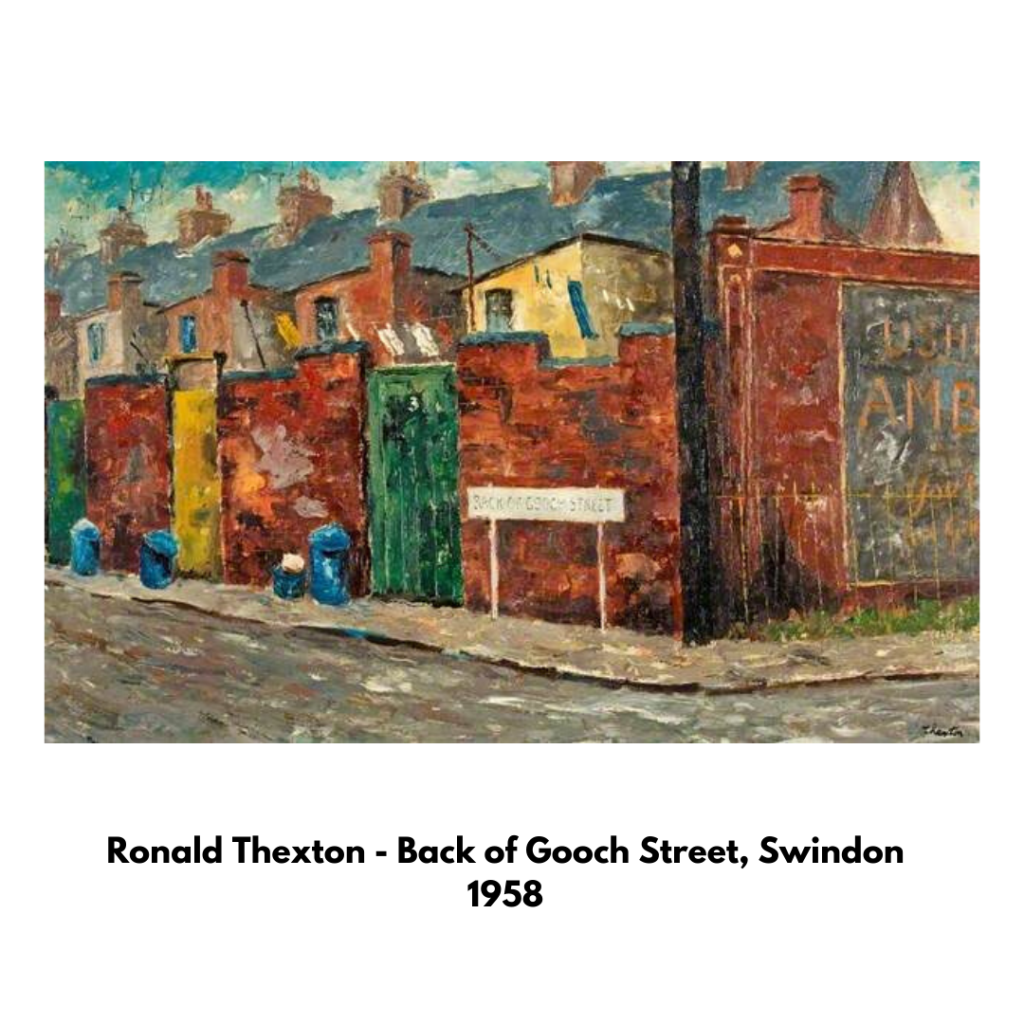

Realism focuses with an unflinching gaze on the solidity of the real world in front of us. It gathered force as an art movement in the mid-nineteenth century, as artists began to break from High Art tradition and paint subjects from everyday life as naturalistically as possible. Realist paintings depicted ‘gritty’ scenes of working class life, both rural and urban. This choice of subject matter, along with its naturalistic treatment, shocked traditional art audiences used to the artificiality of historic battles and religious scenes!

Modern realist artworks are often still edgy in subject matter and style, and refuse to shy away from the realities of existence. As a reaction to World War I, the 1920s saw a ‘return-to-order’, as artists began to shun pre-war experimentation and return to more traditional realist approaches. In 1938, this was followed by the formation of the group of realist artists known as the Euston Road School. This group included Lawrence Gowing whose work features in the Swindon Collection. Throughout the 1950s, British ‘Kitchen-Sink’ artists continued to follow in this realist tradition. Realism is now used to describe artworks painted in an almost photographic way.

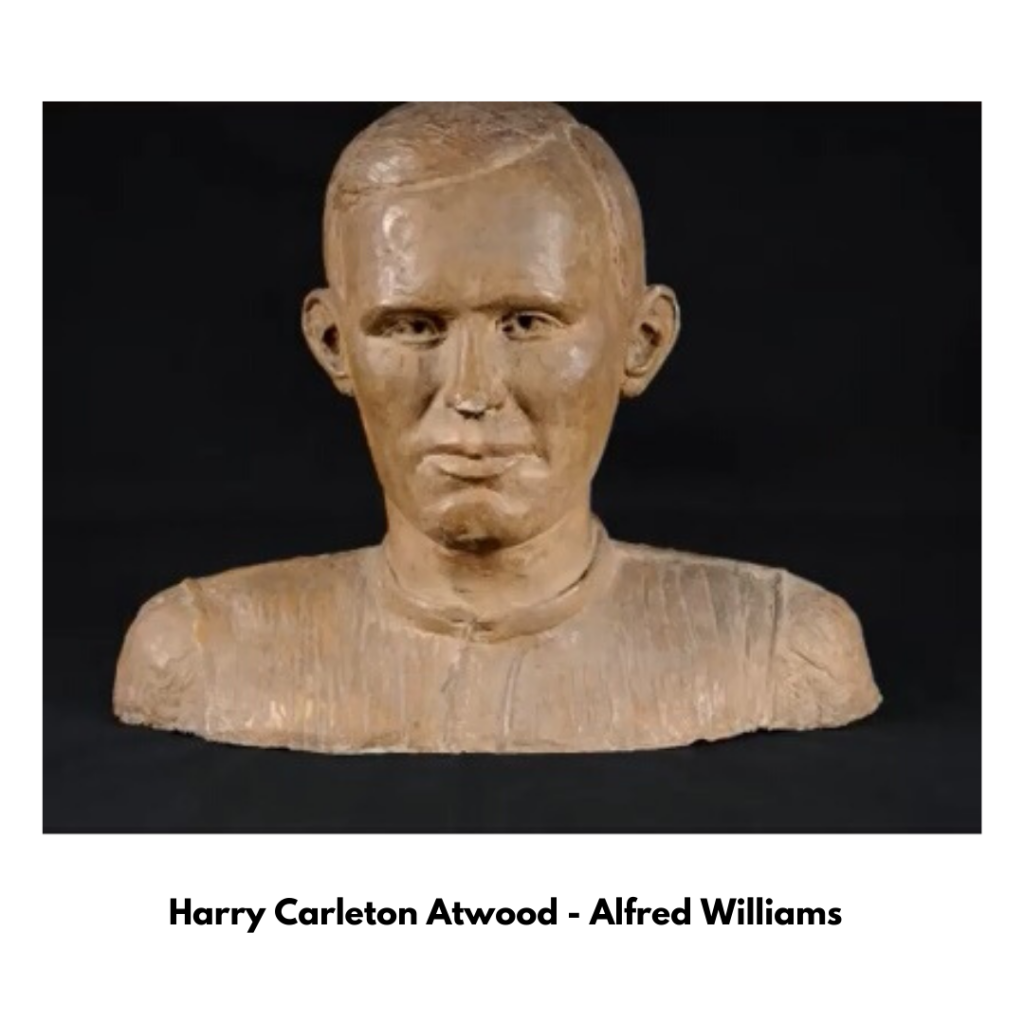

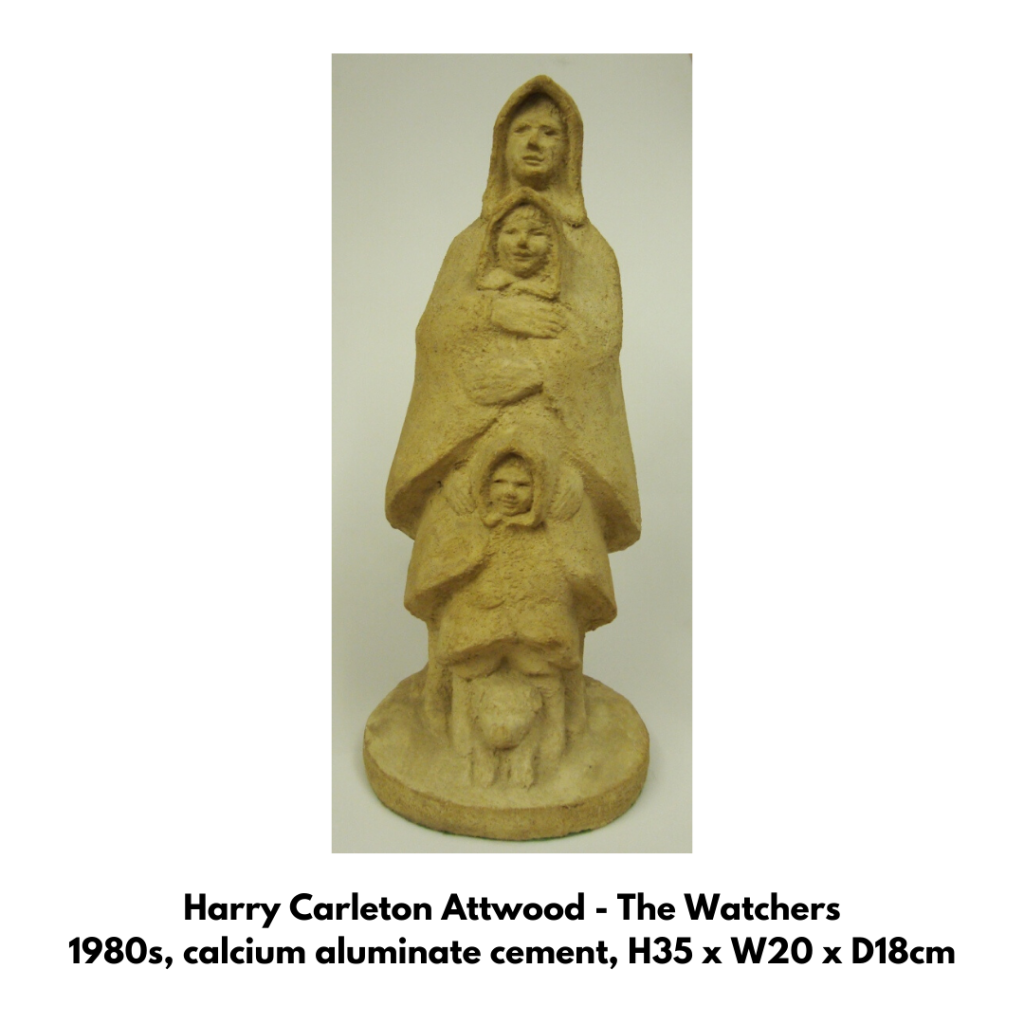

SCULPTURE:

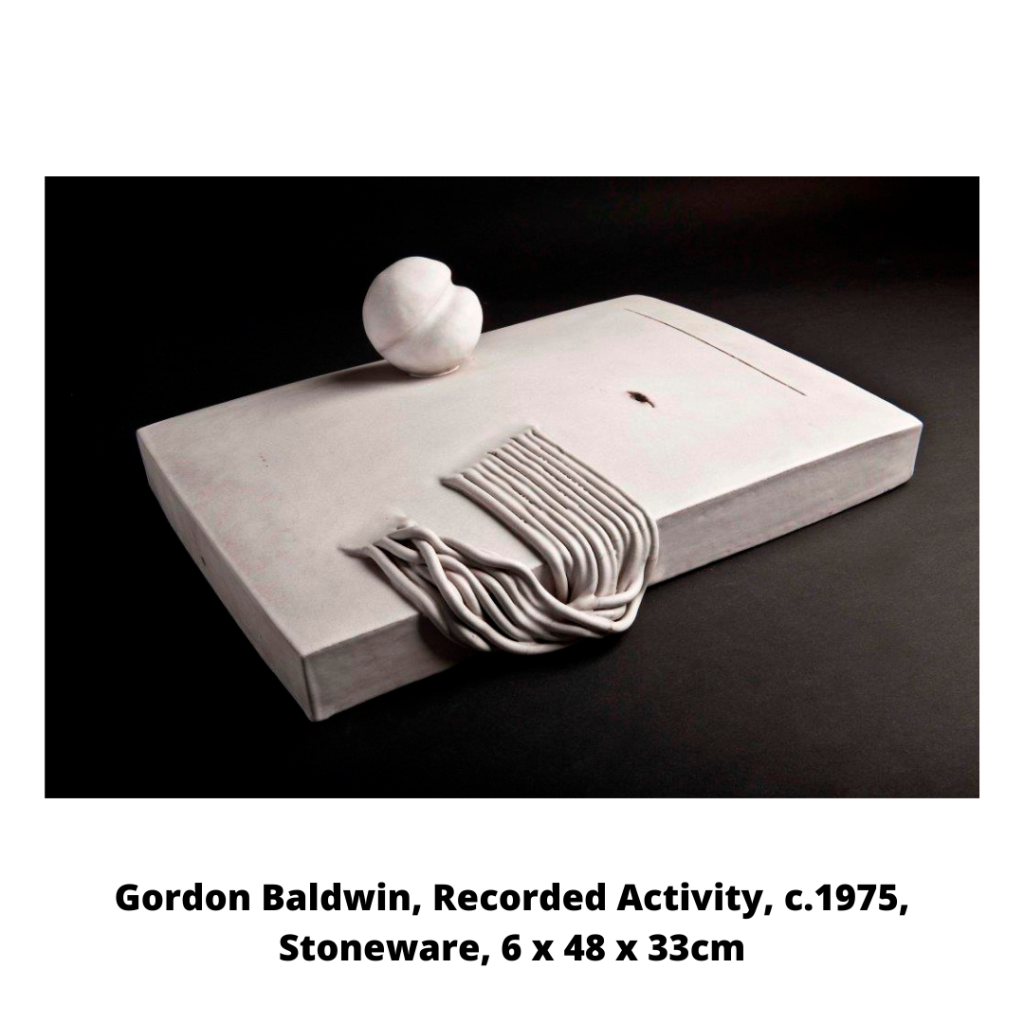

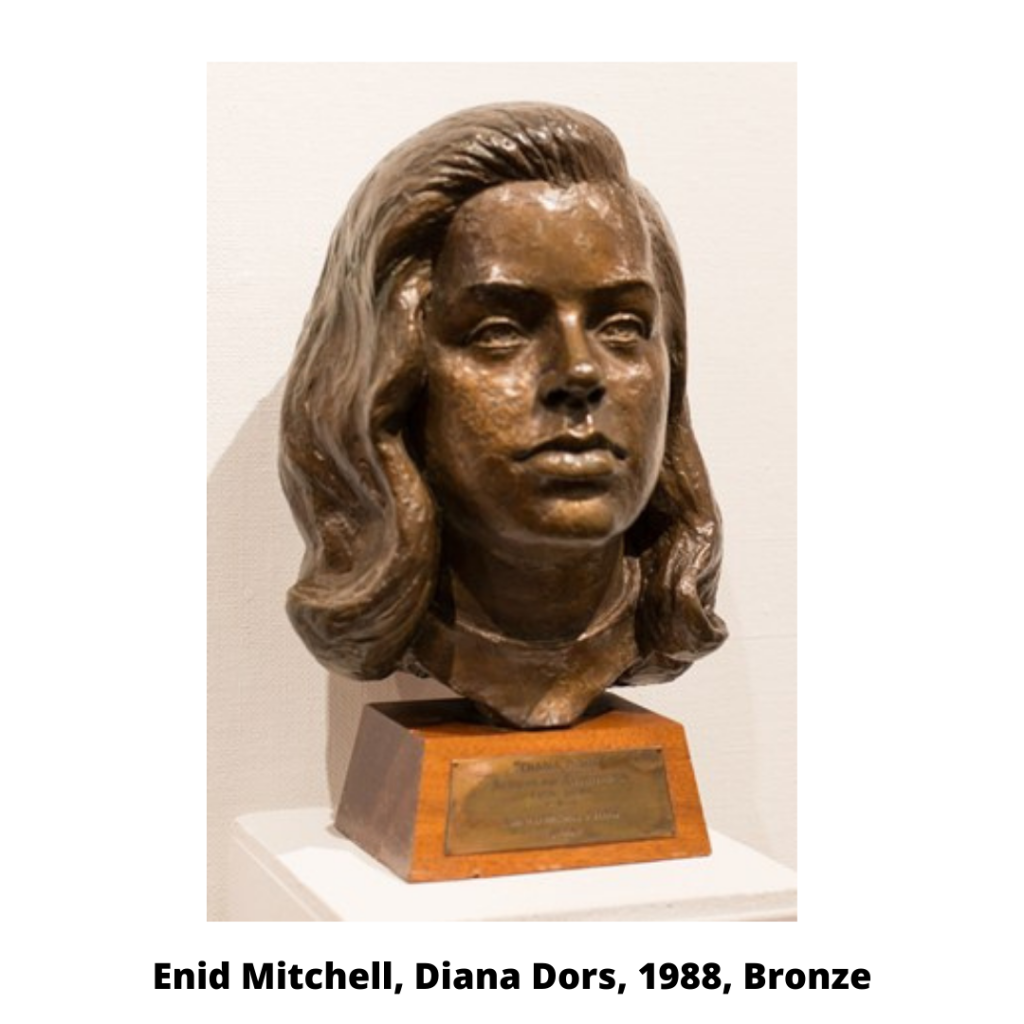

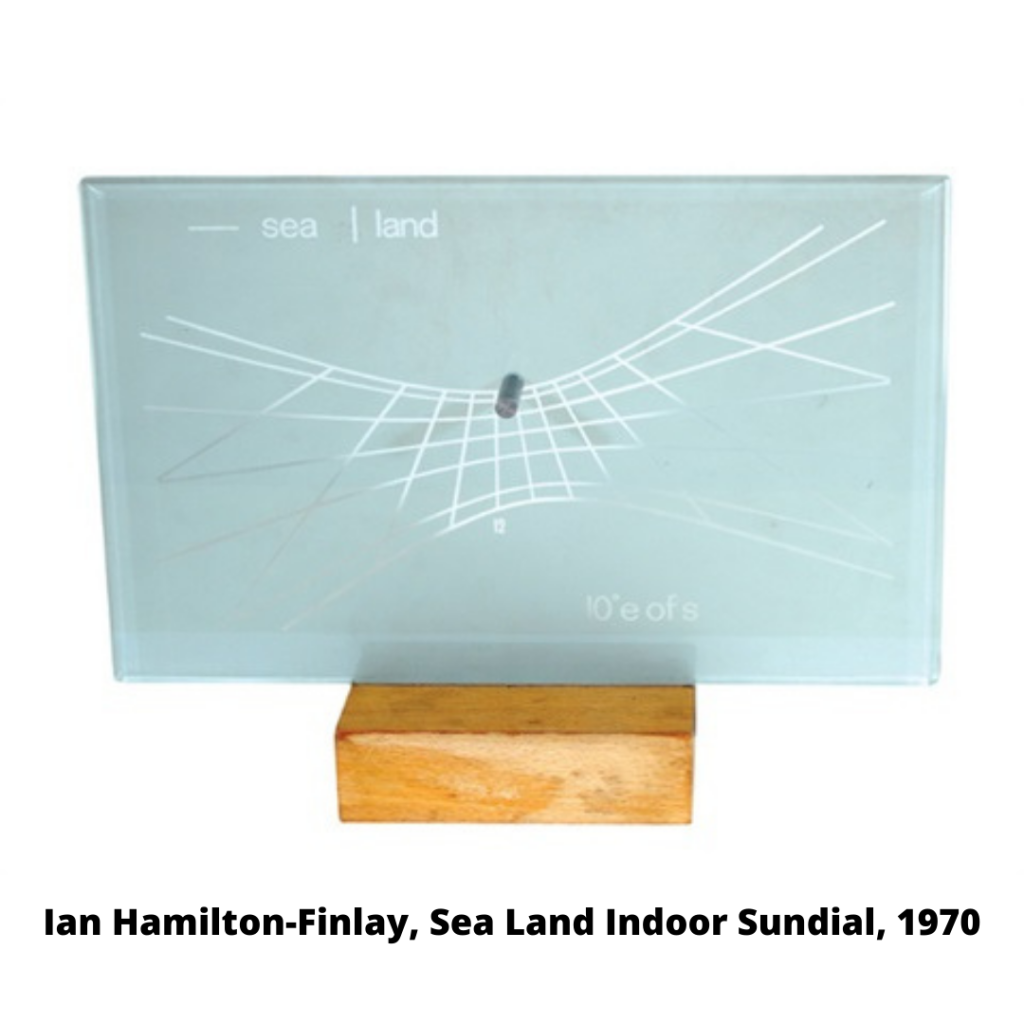

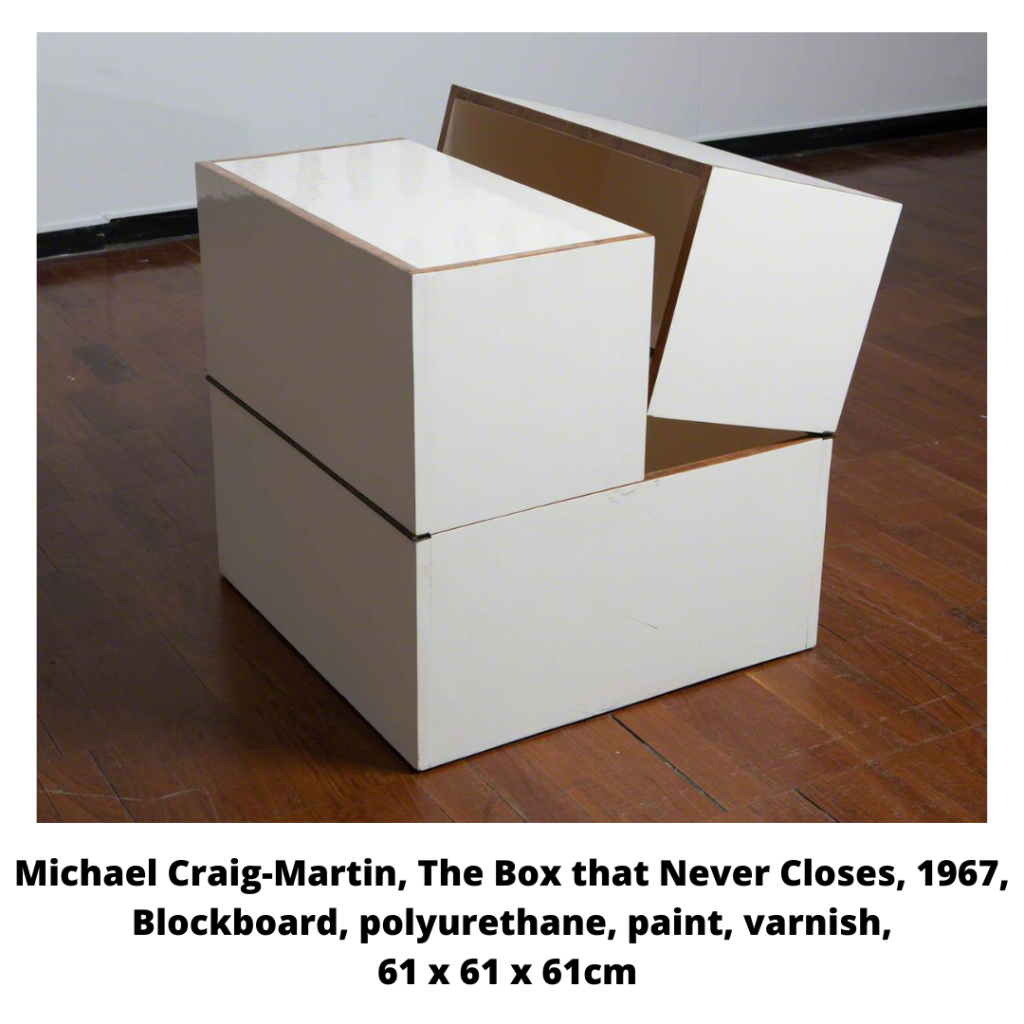

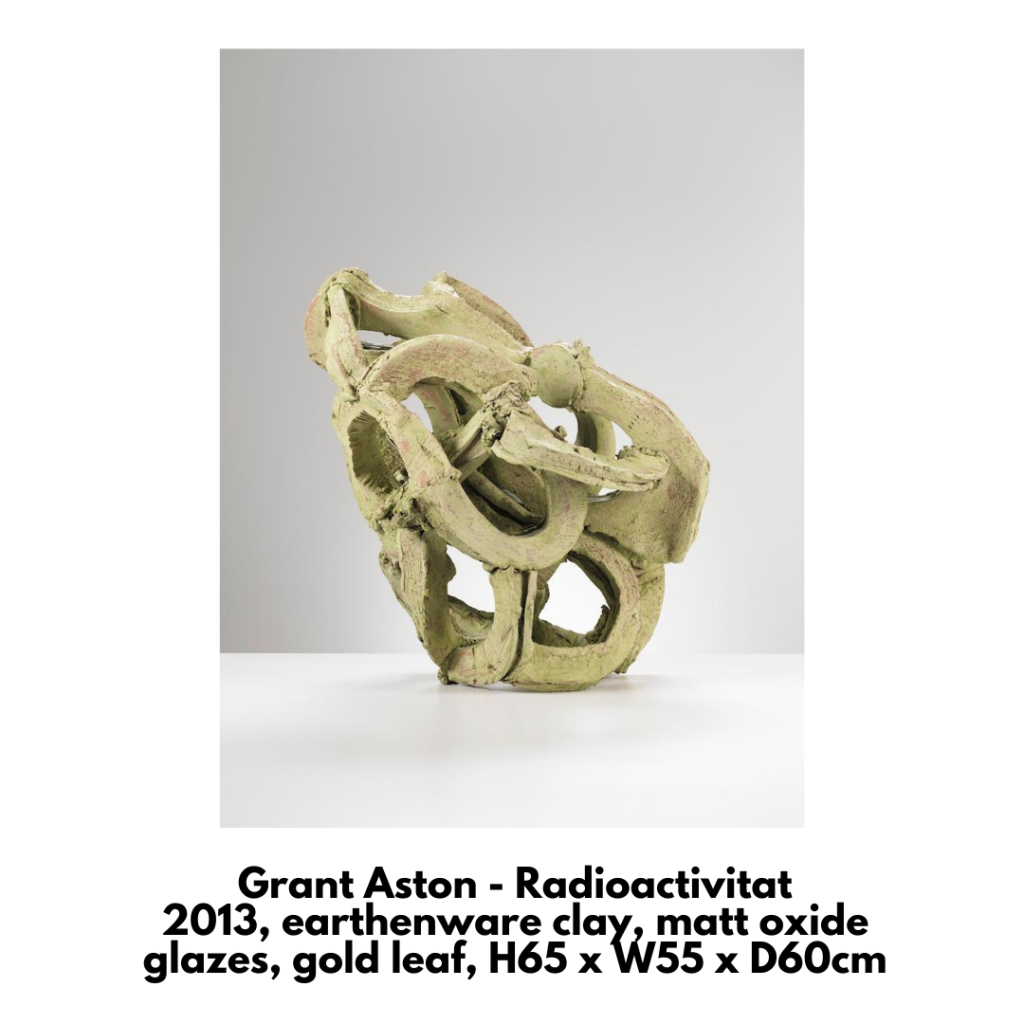

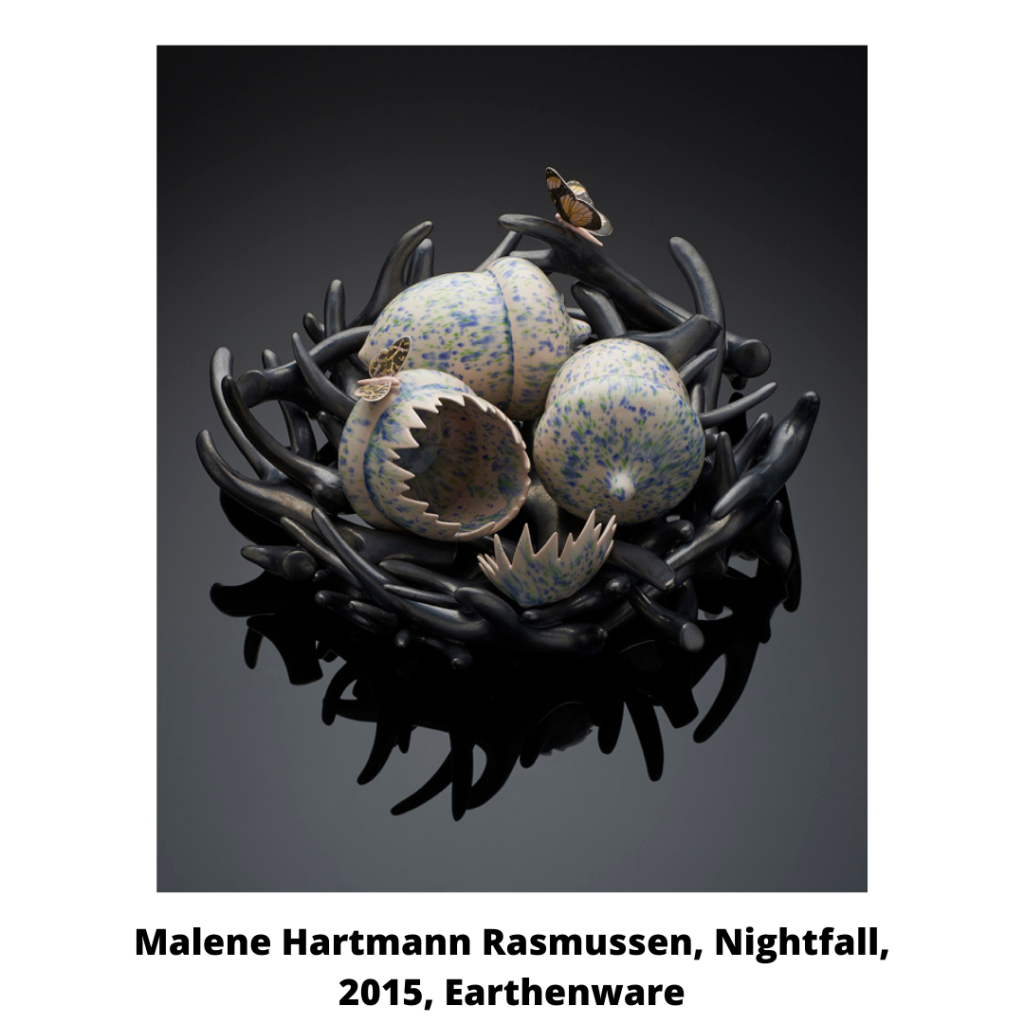

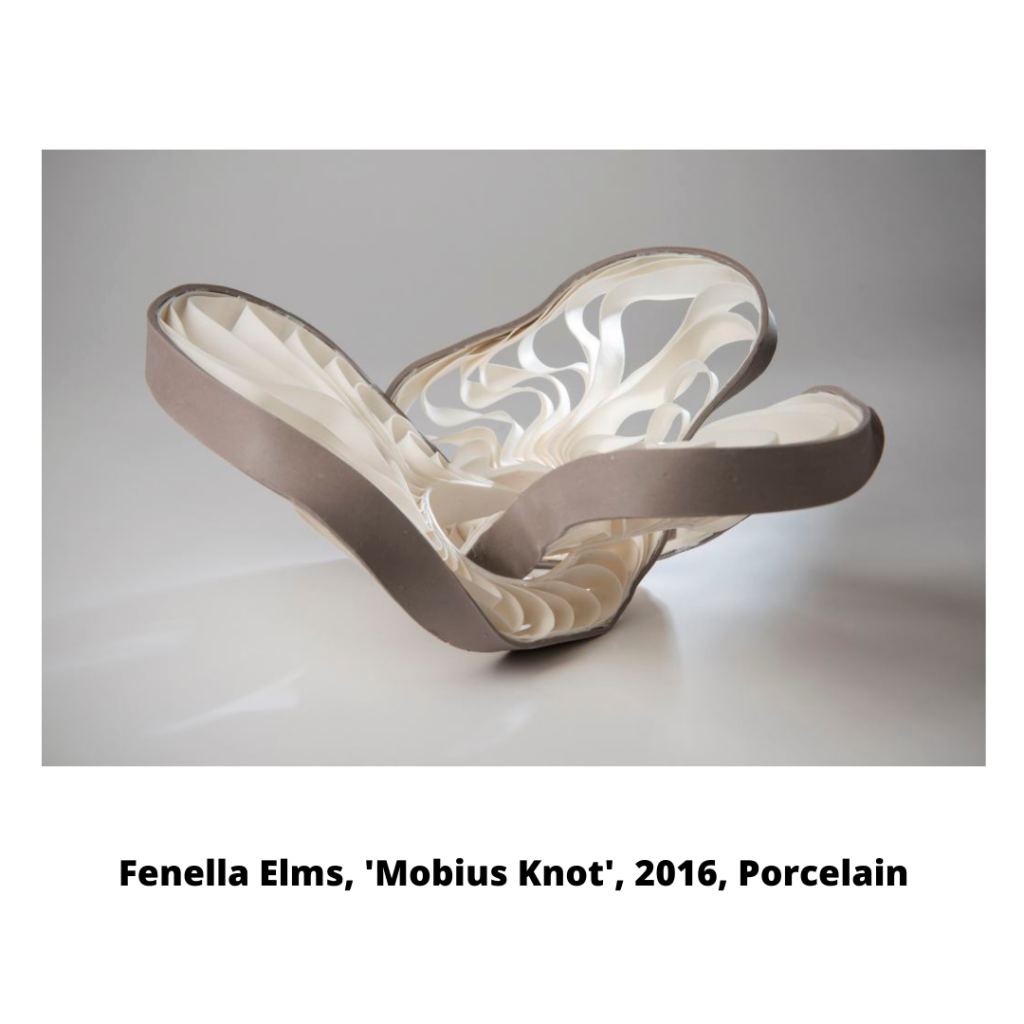

Traditionally speaking, a sculpture is a piece of solid, static art made by the processes of casting or carving expensive materials such as bronze and marble. As such, prior to the 20th Century, sculpture was often reserved for important subject matter, and represented religious, mythological, allegorical, royal, military or political figures. In the 1900s, the boundaries of three-dimensional art were blown wide open! All of a sudden, any medium could be used in art practice; fabric, glass, plastic, rubber… From gigantic soft deserts to minimalist piles of bricks, modern artists changed the nature of the art object and our relationship with space itself.

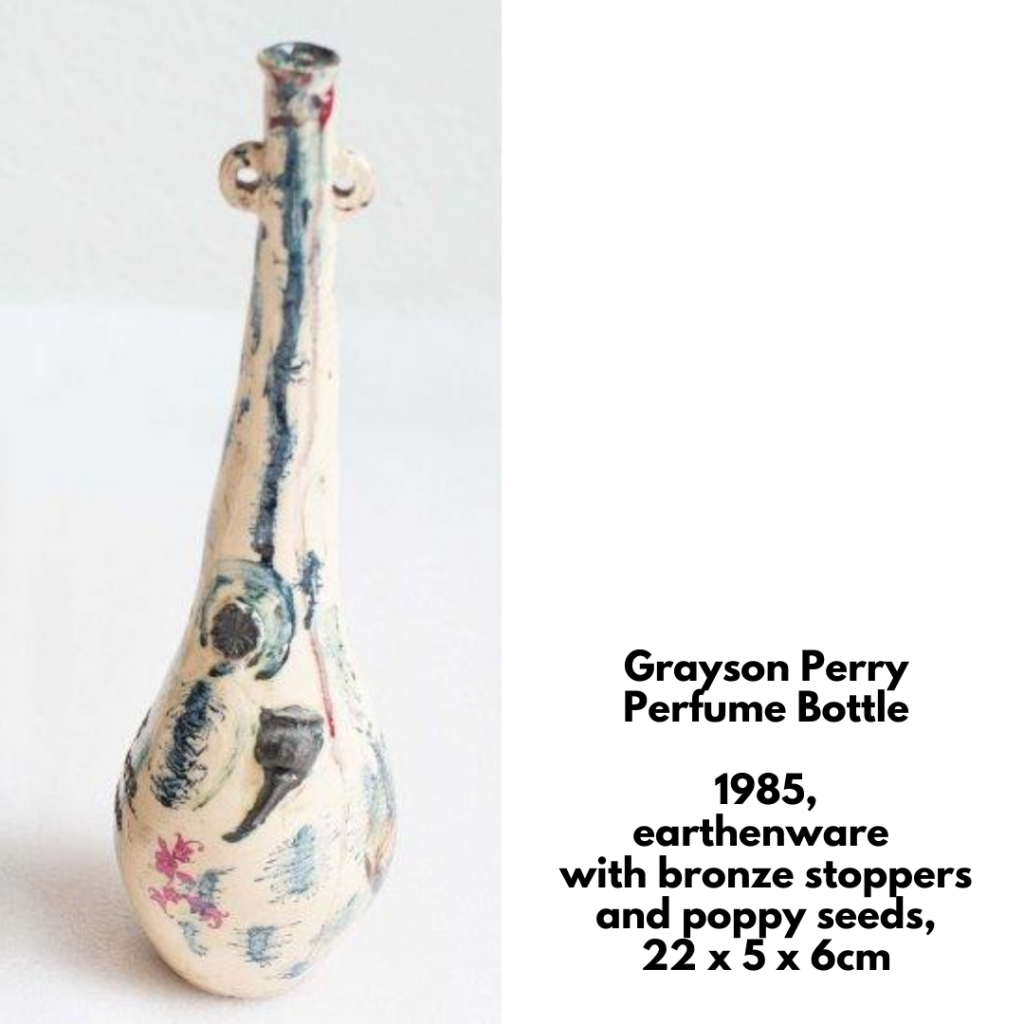

Contemporary artists continue to redefine accepted notions of three-dimensional art. In Swindon’s collection, this is most evident in the blurring of boundaries between studio ceramics and sculptural practice. Though ceramics is traditionally seen as a “craft”, contemporary ceramicists demonstrate the expressive potential and incredible versatility of clay.

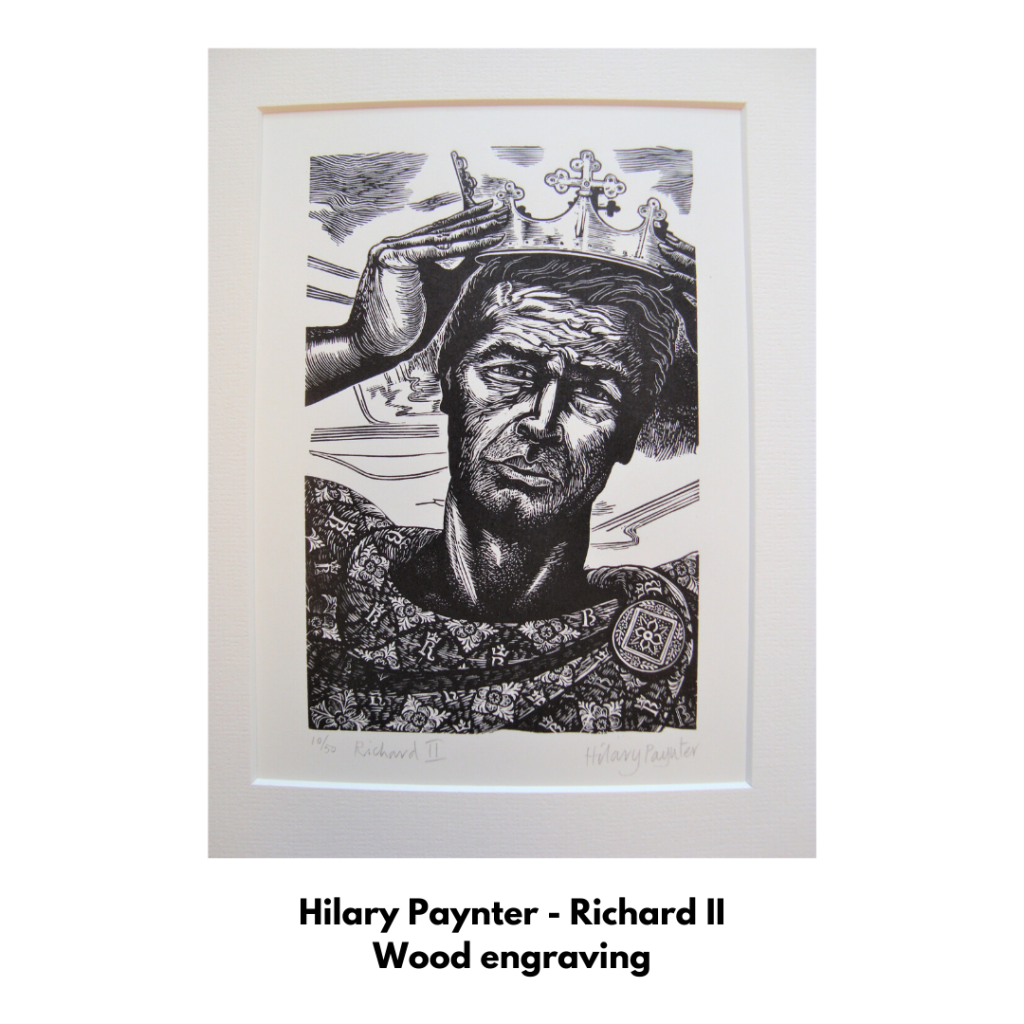

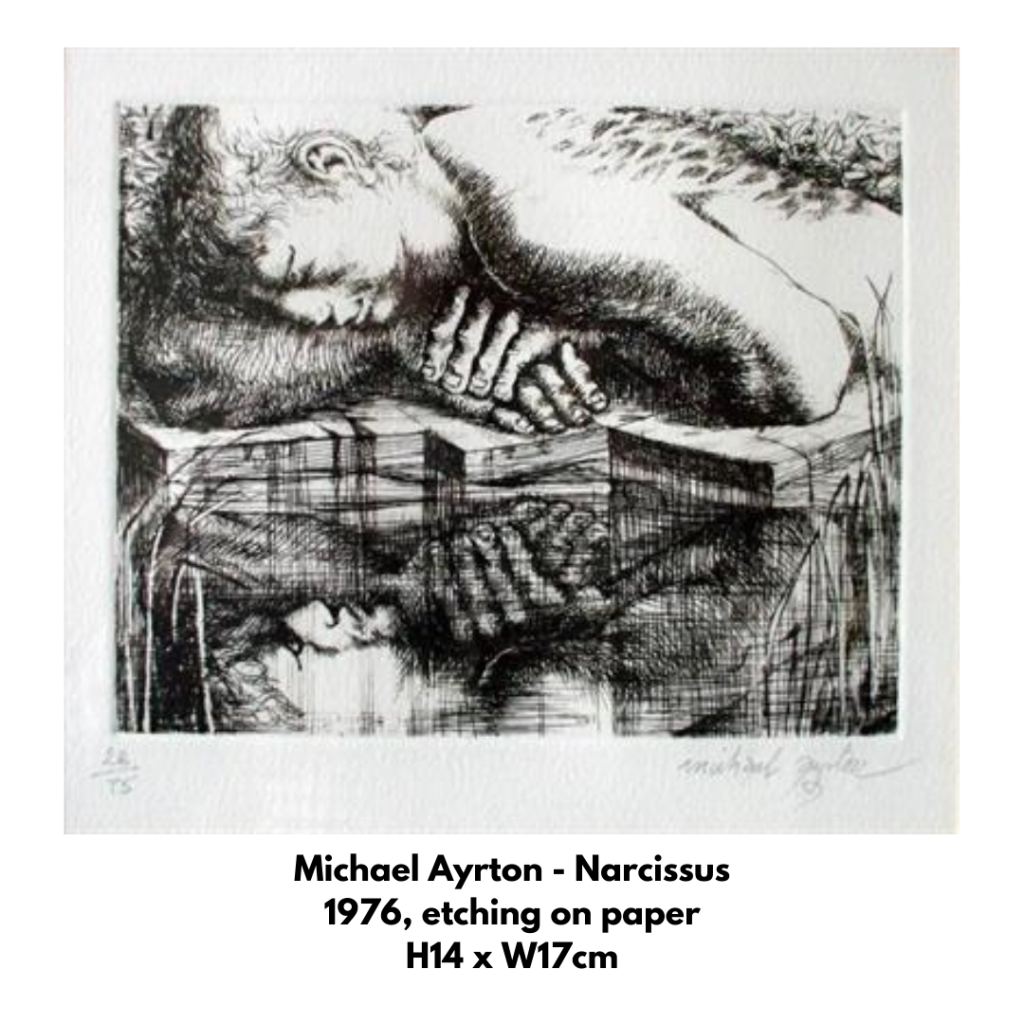

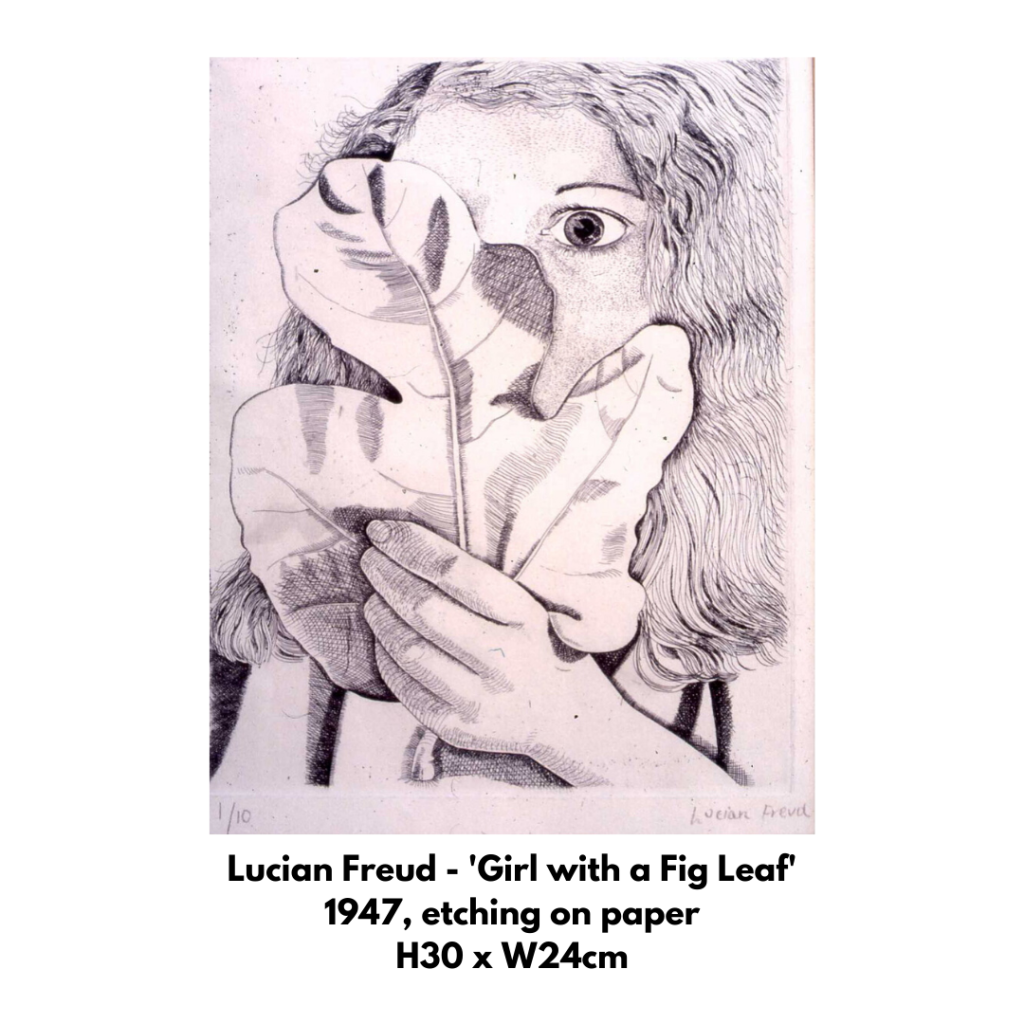

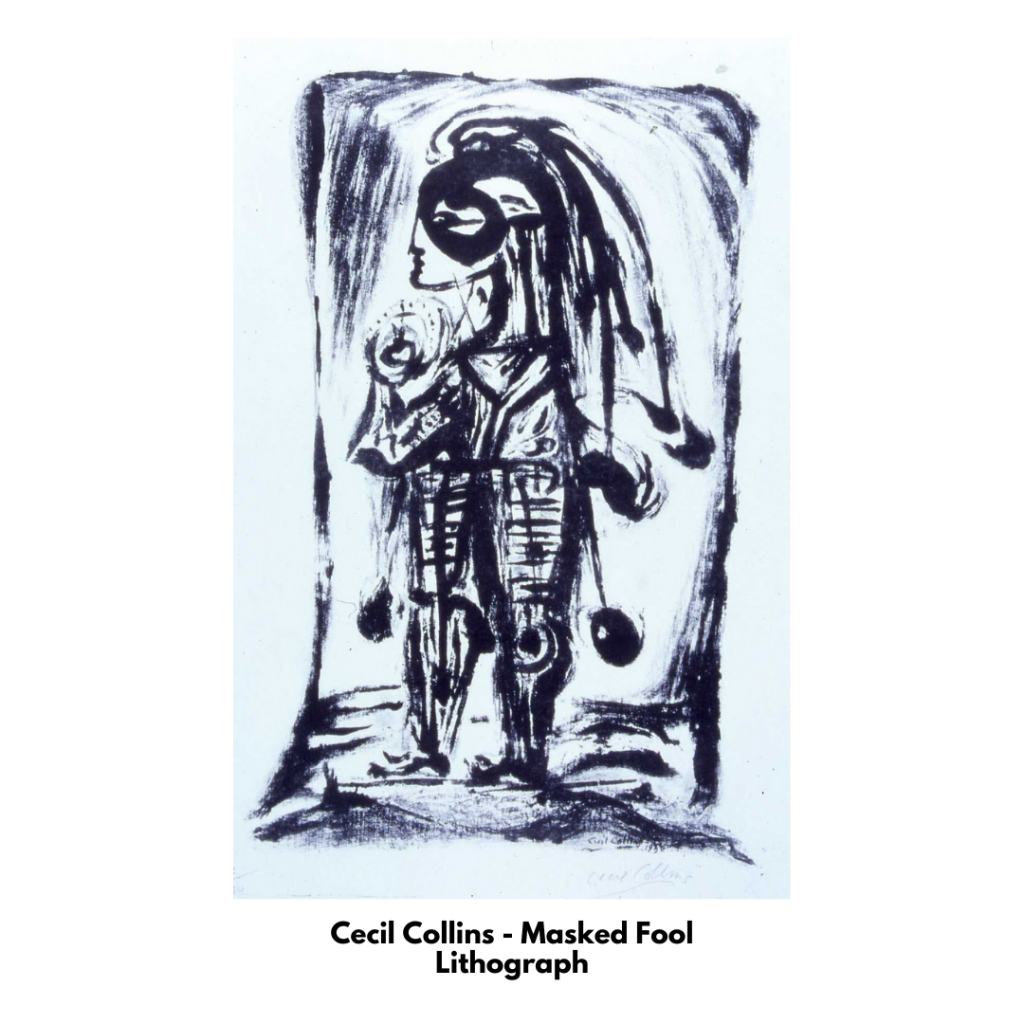

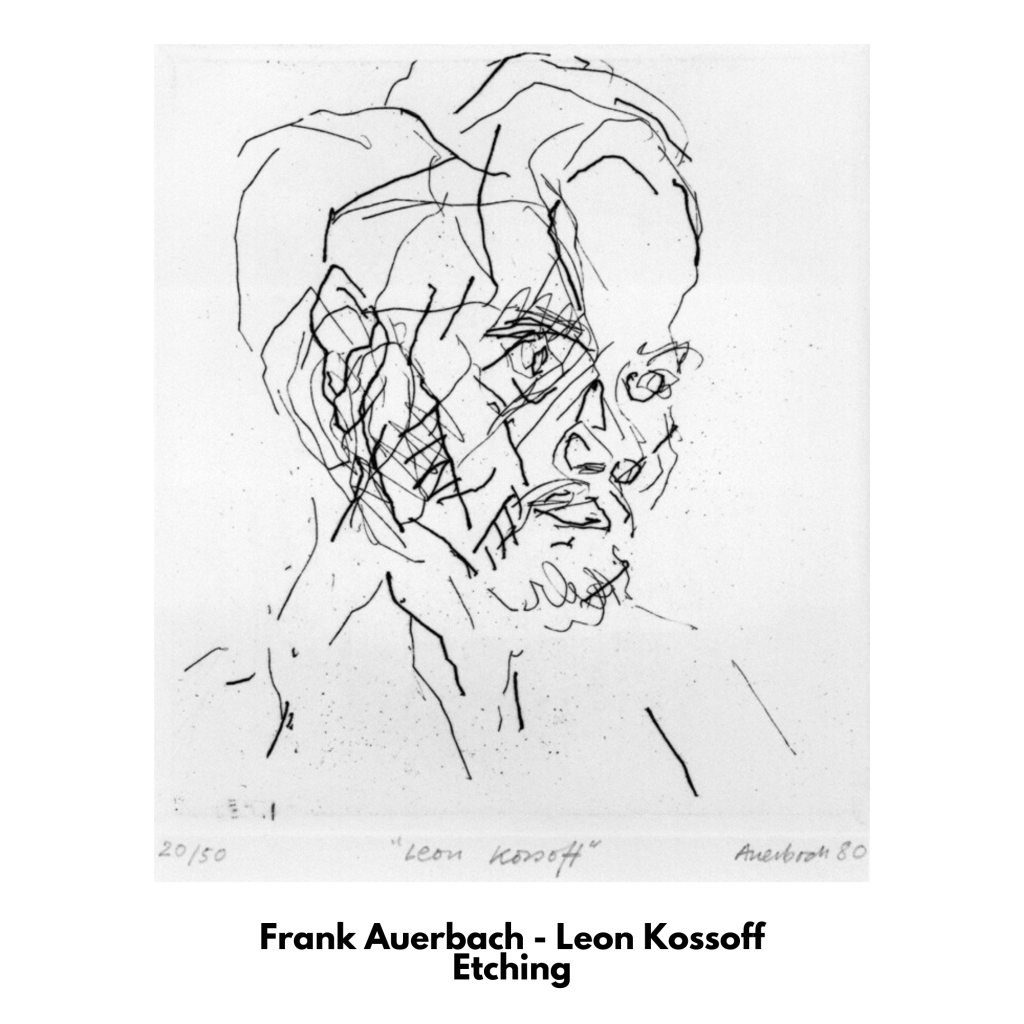

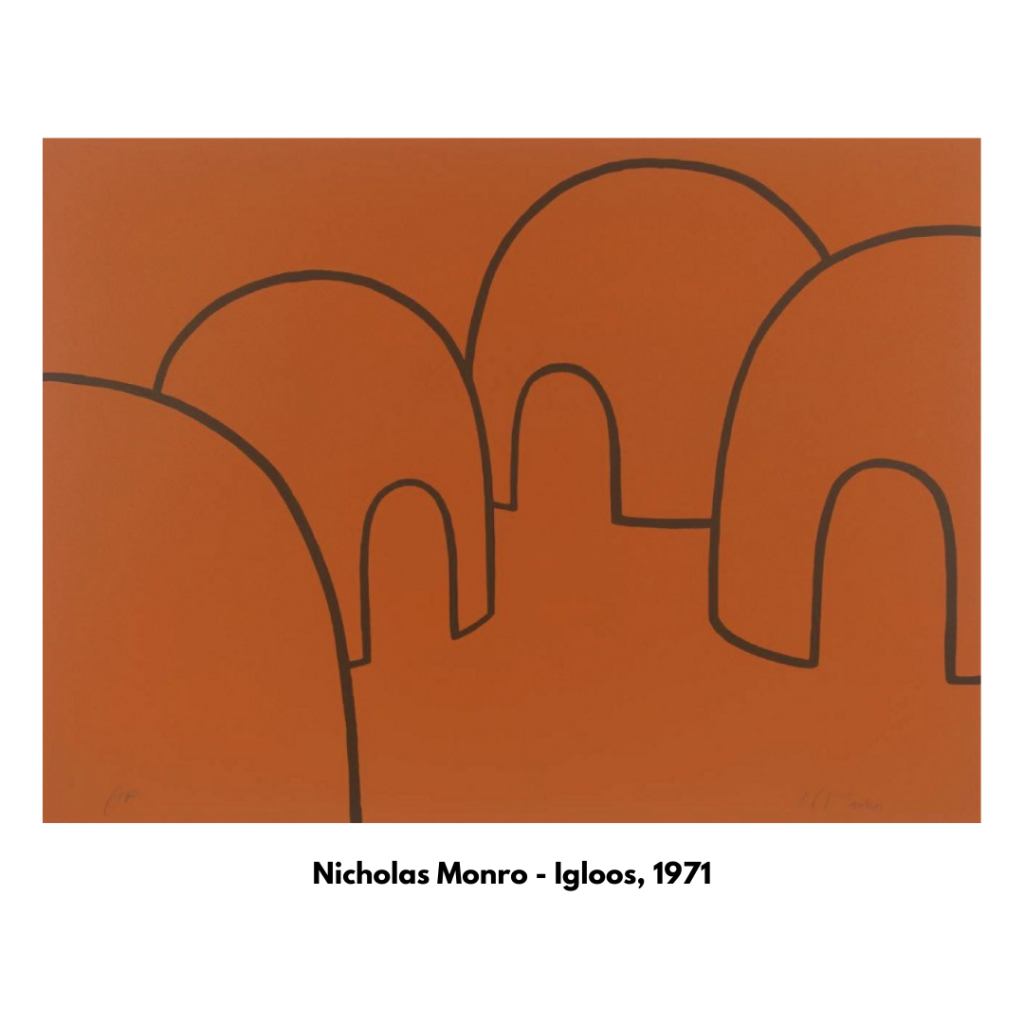

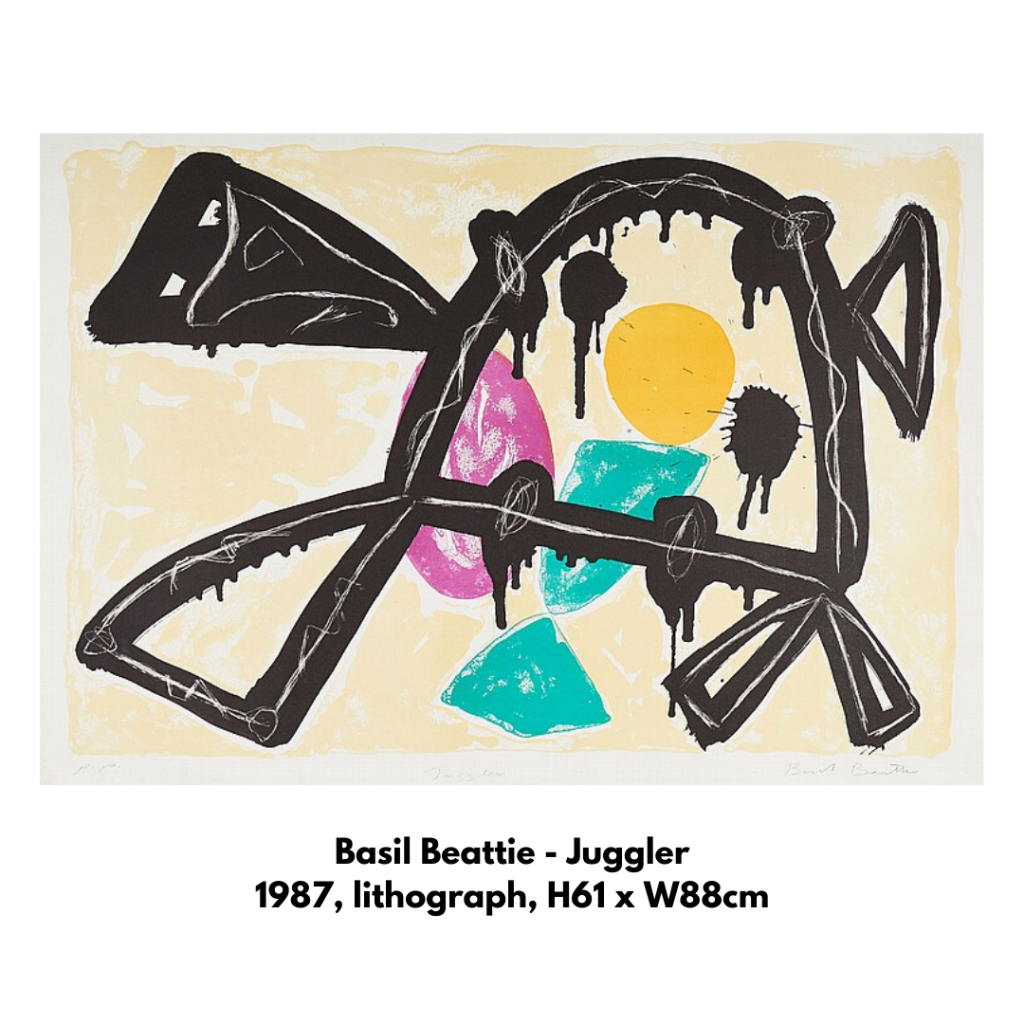

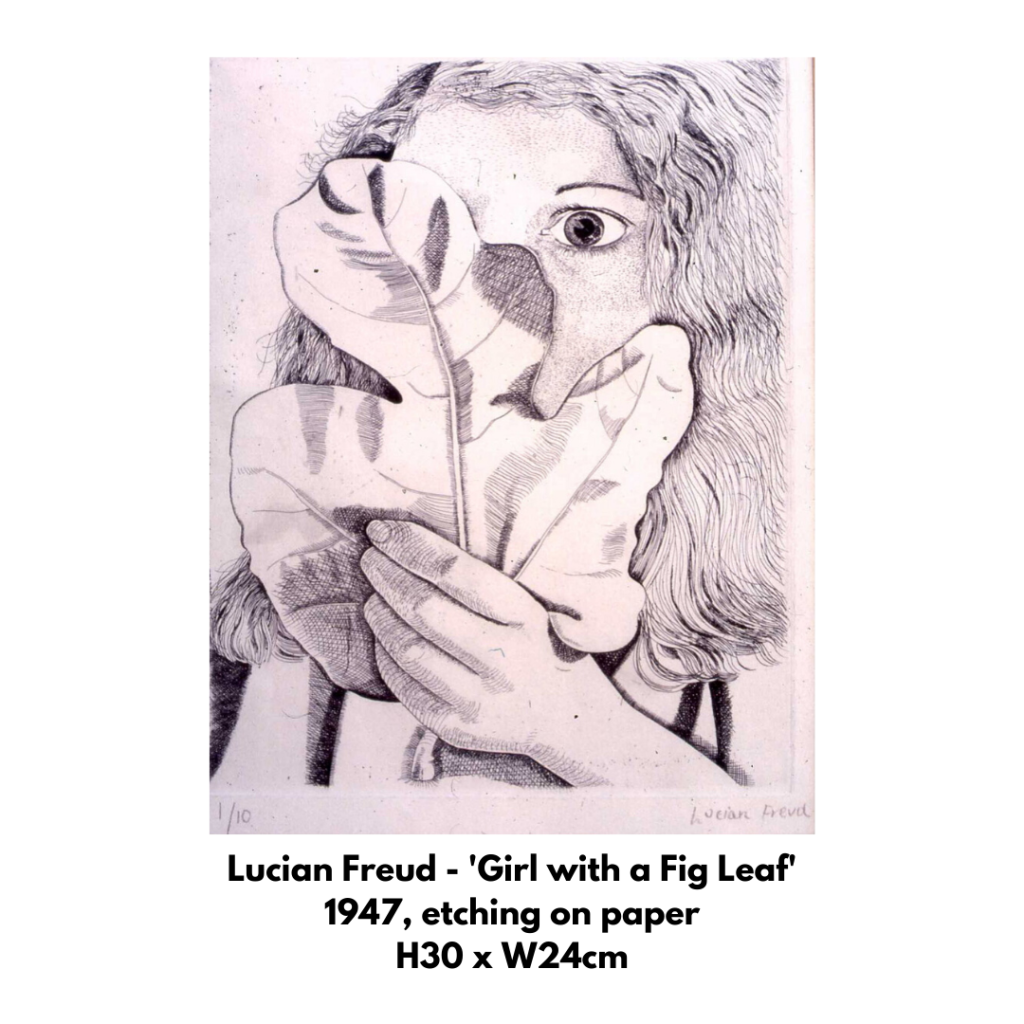

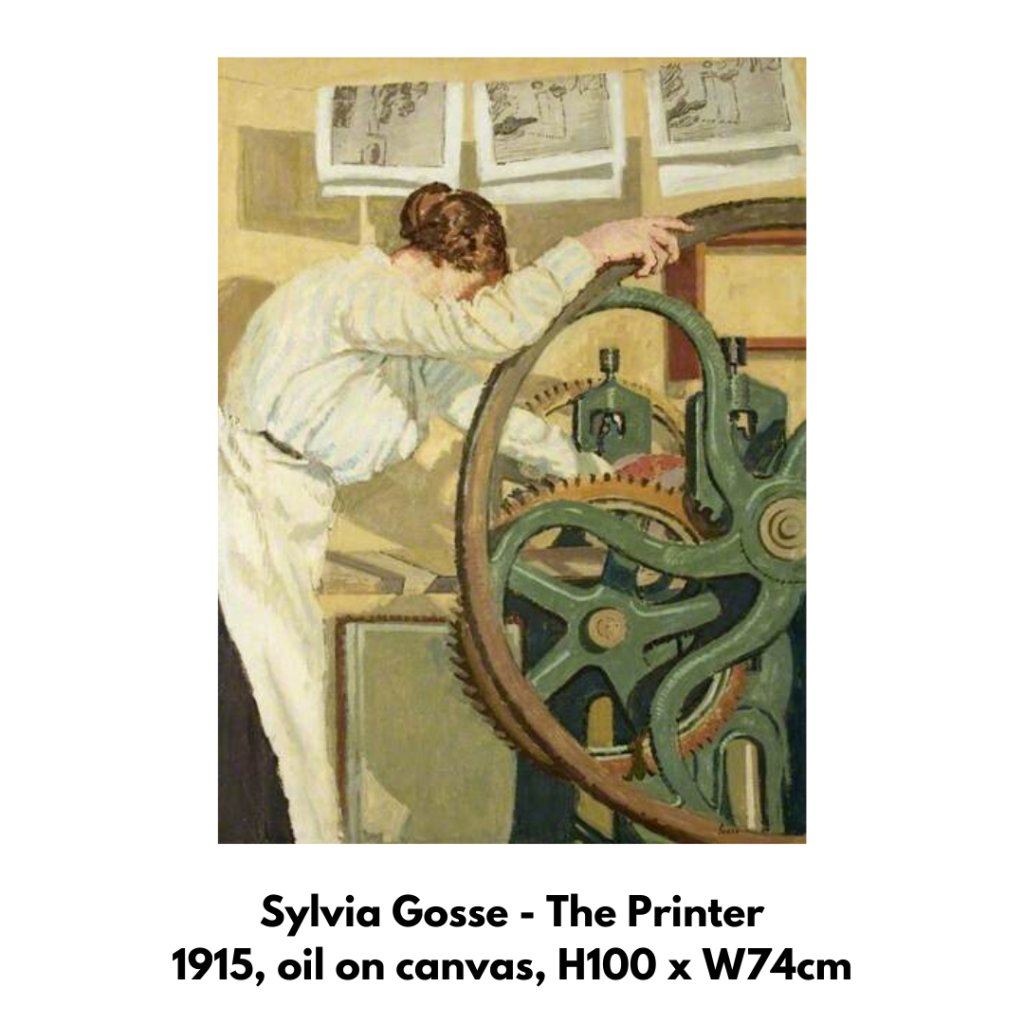

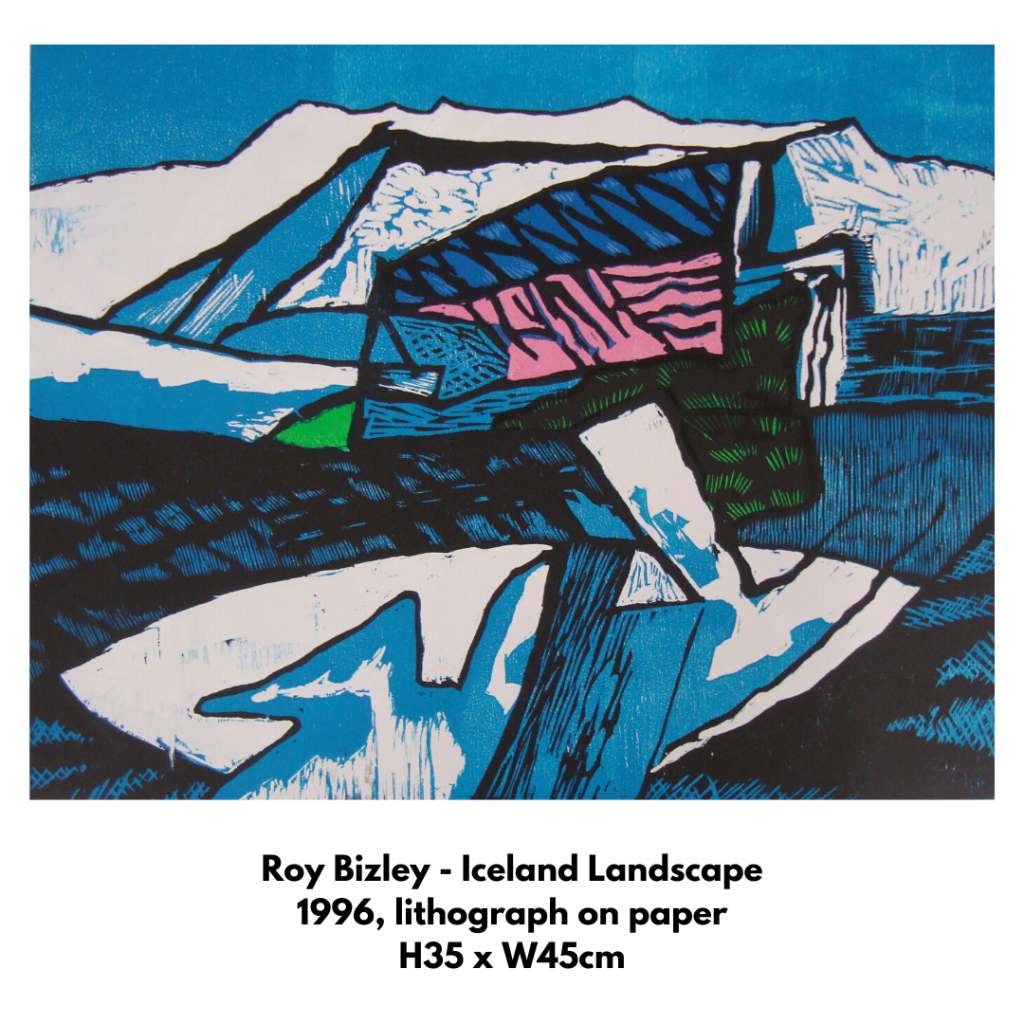

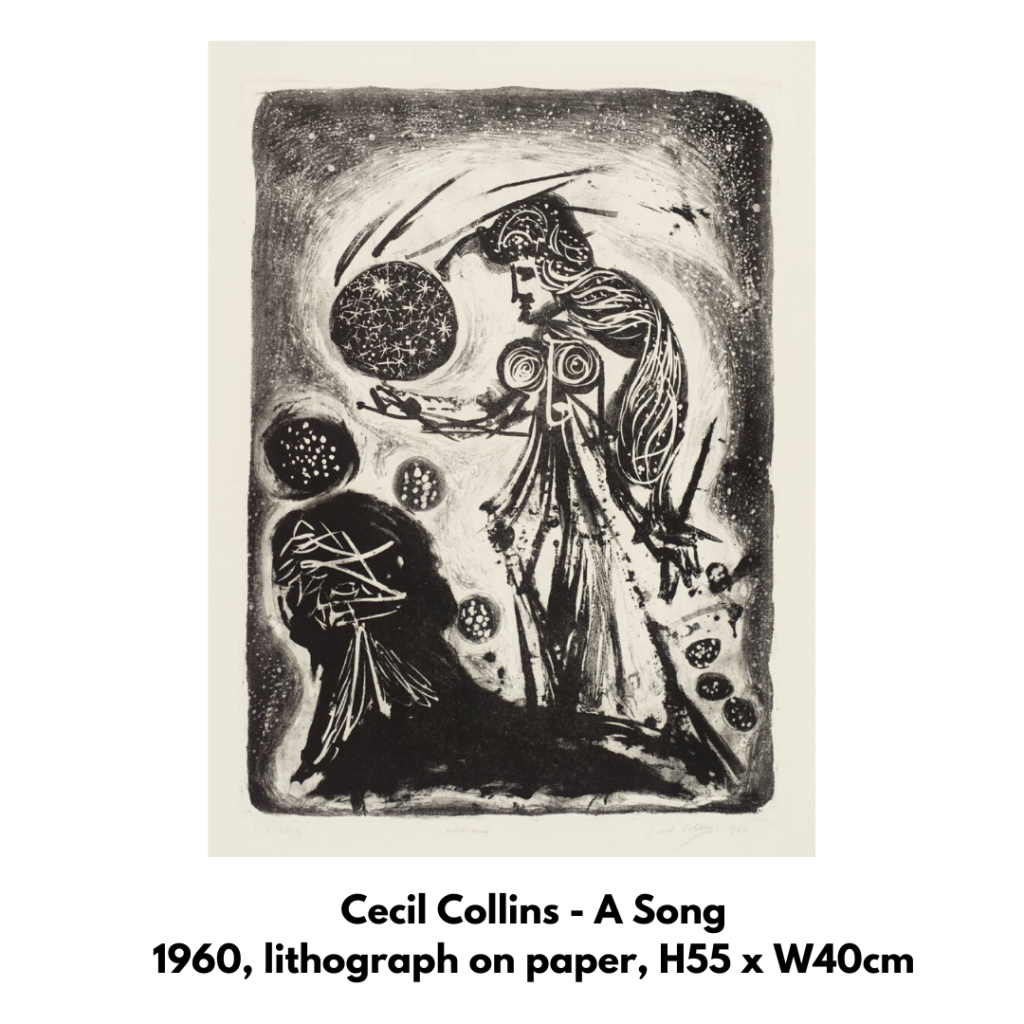

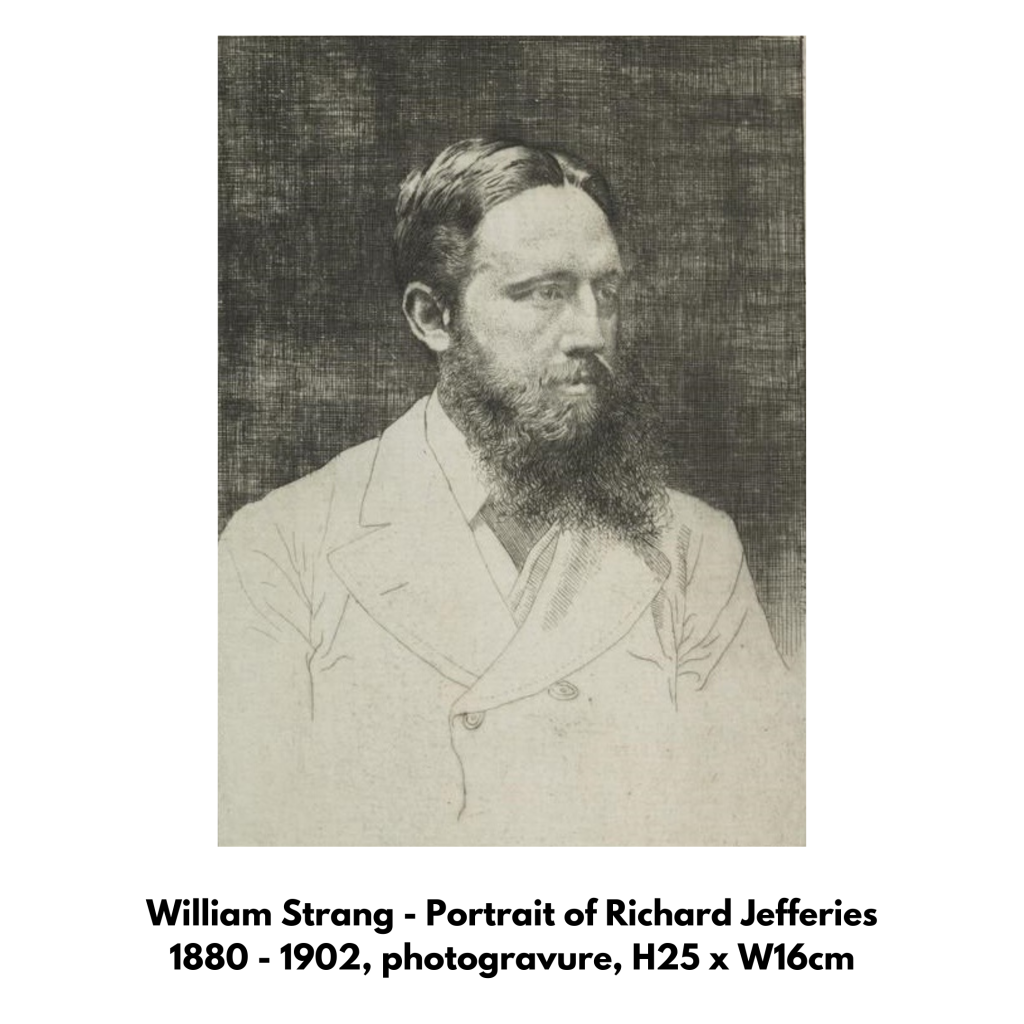

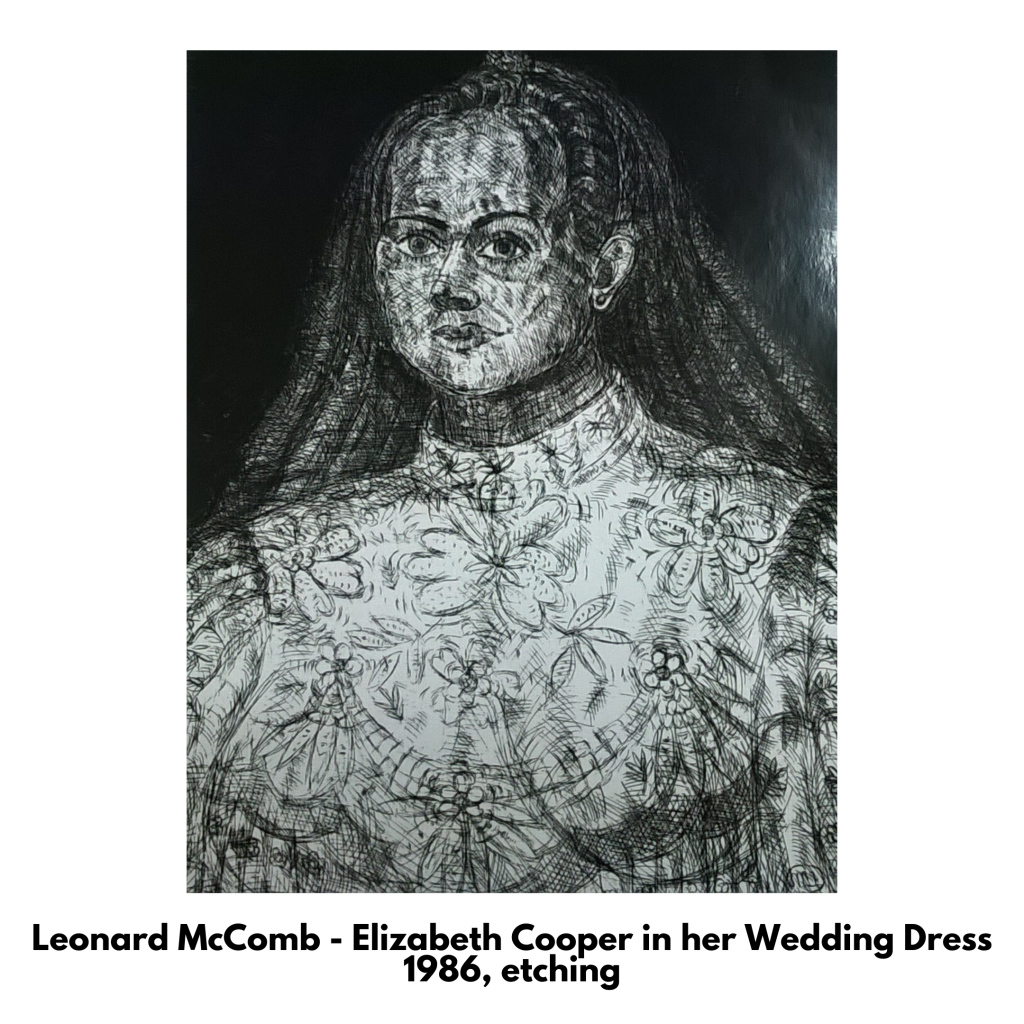

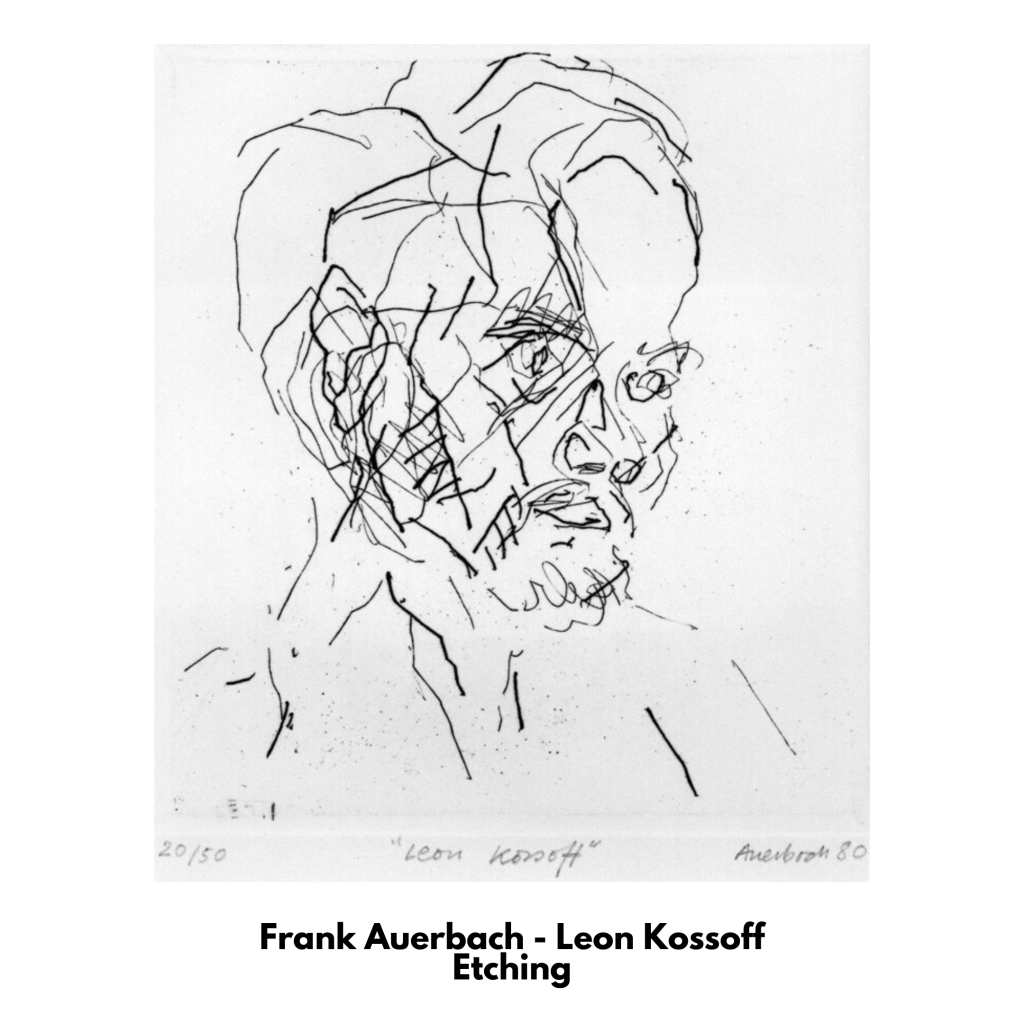

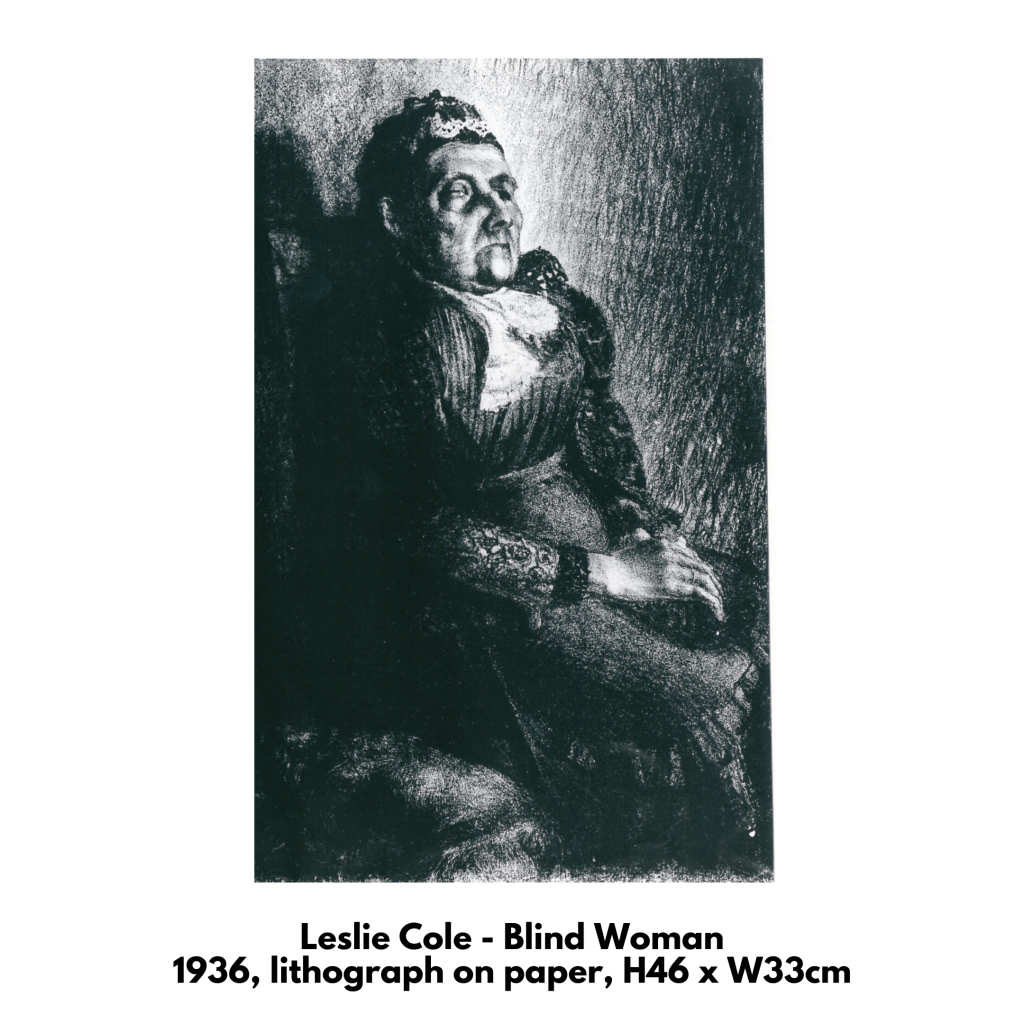

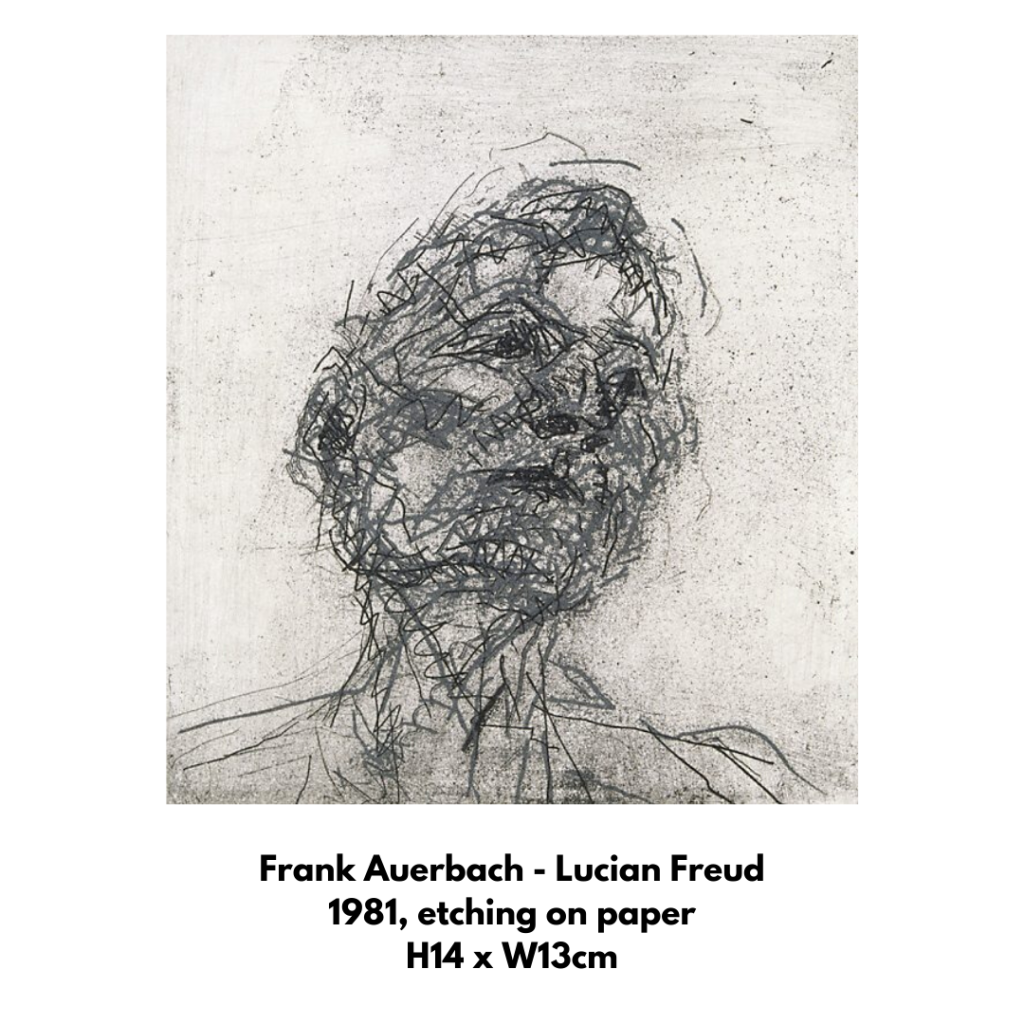

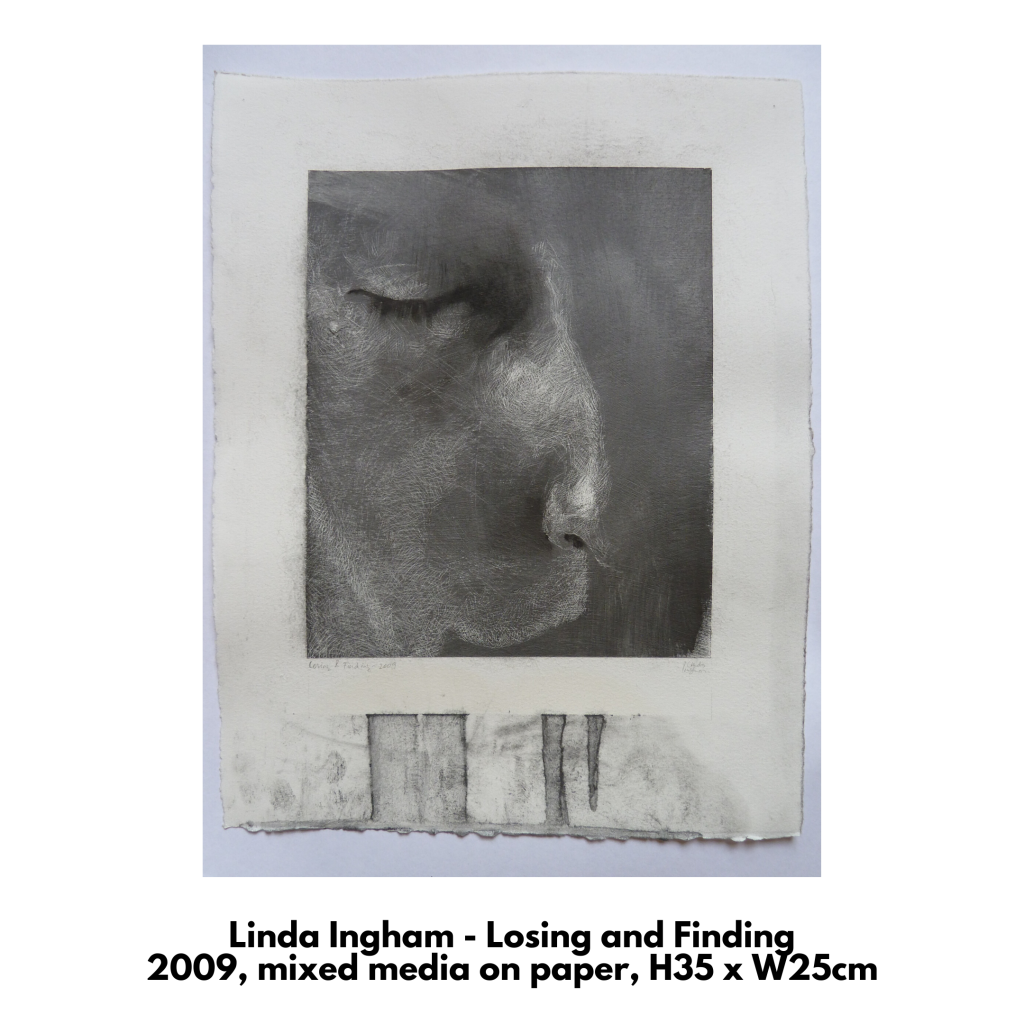

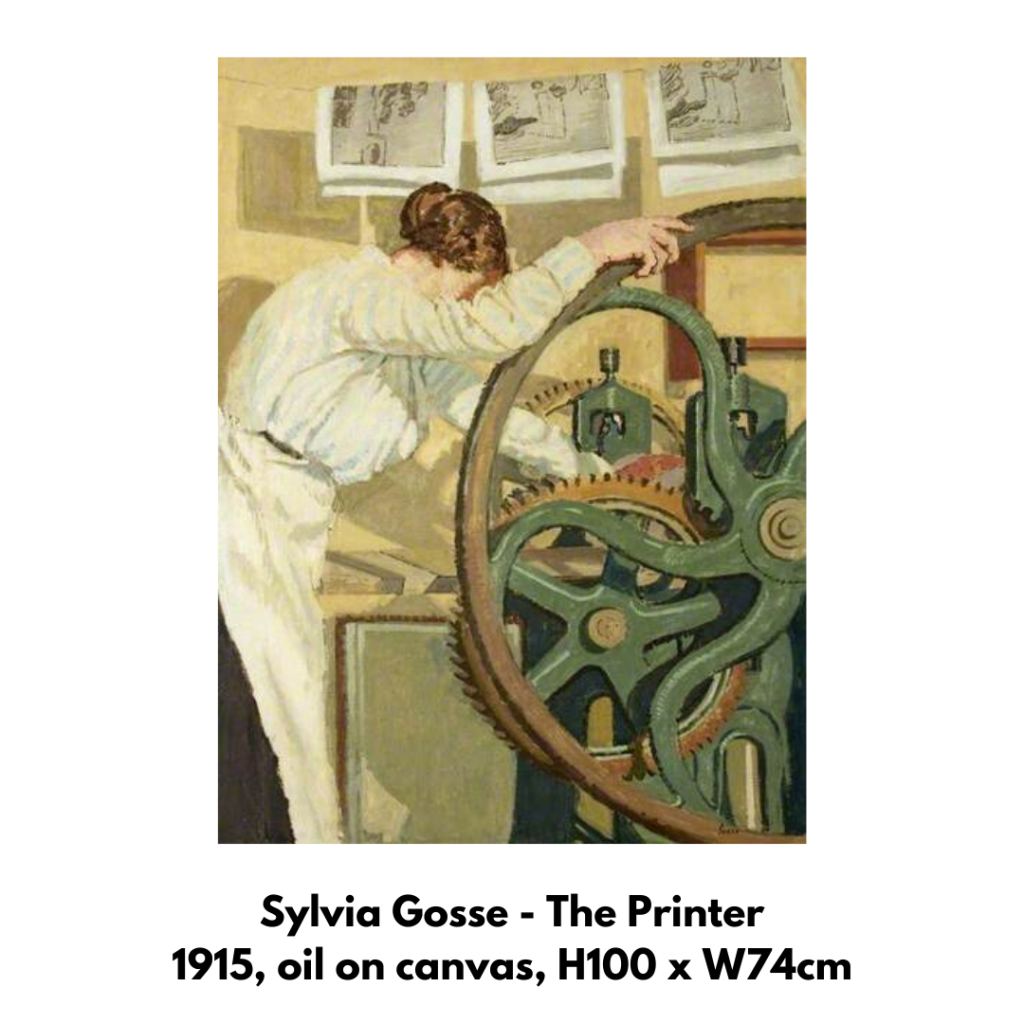

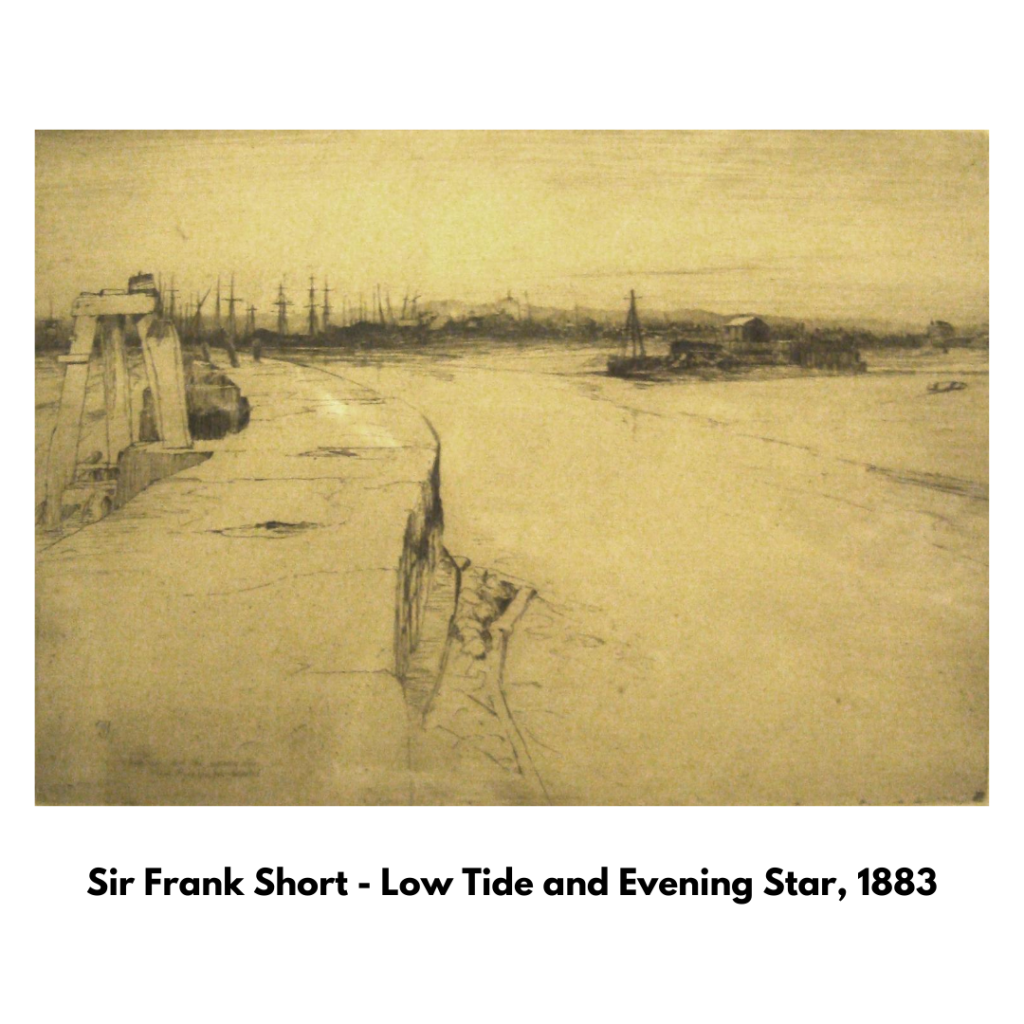

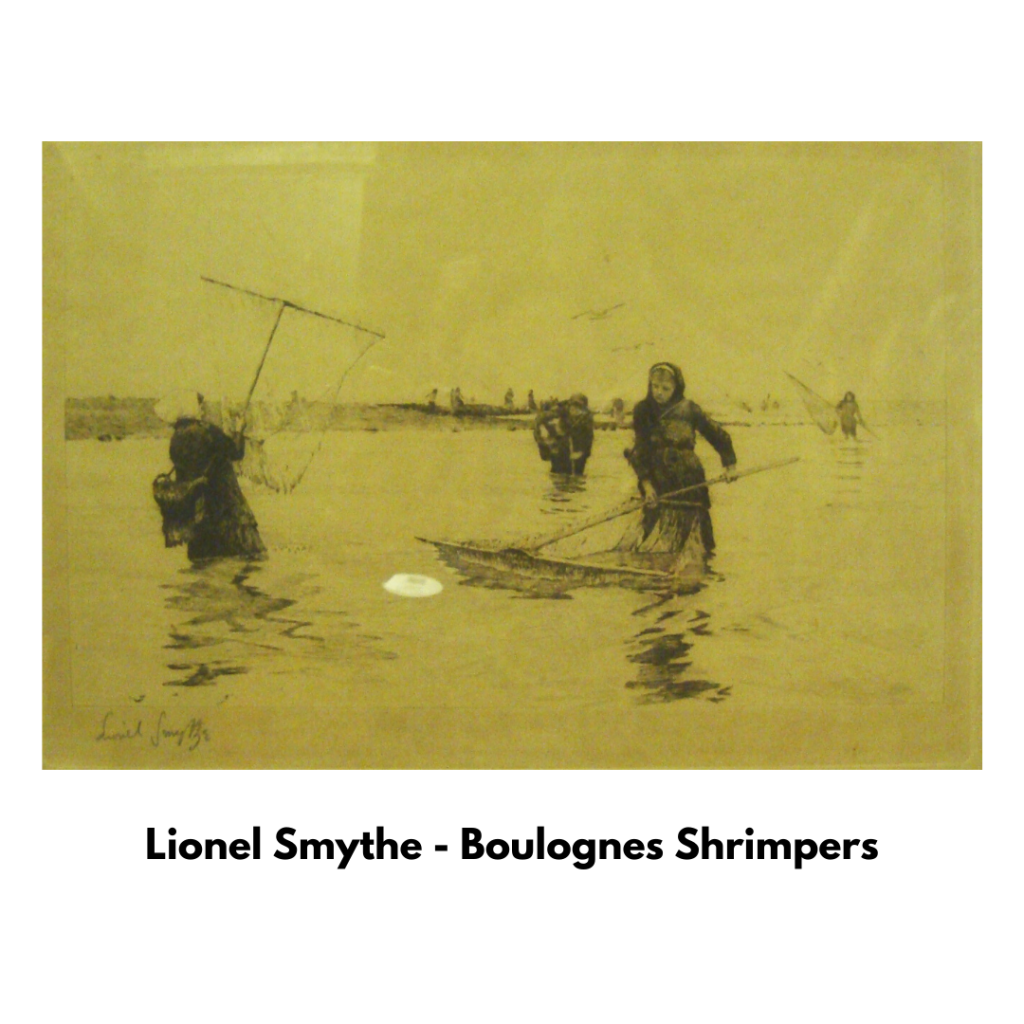

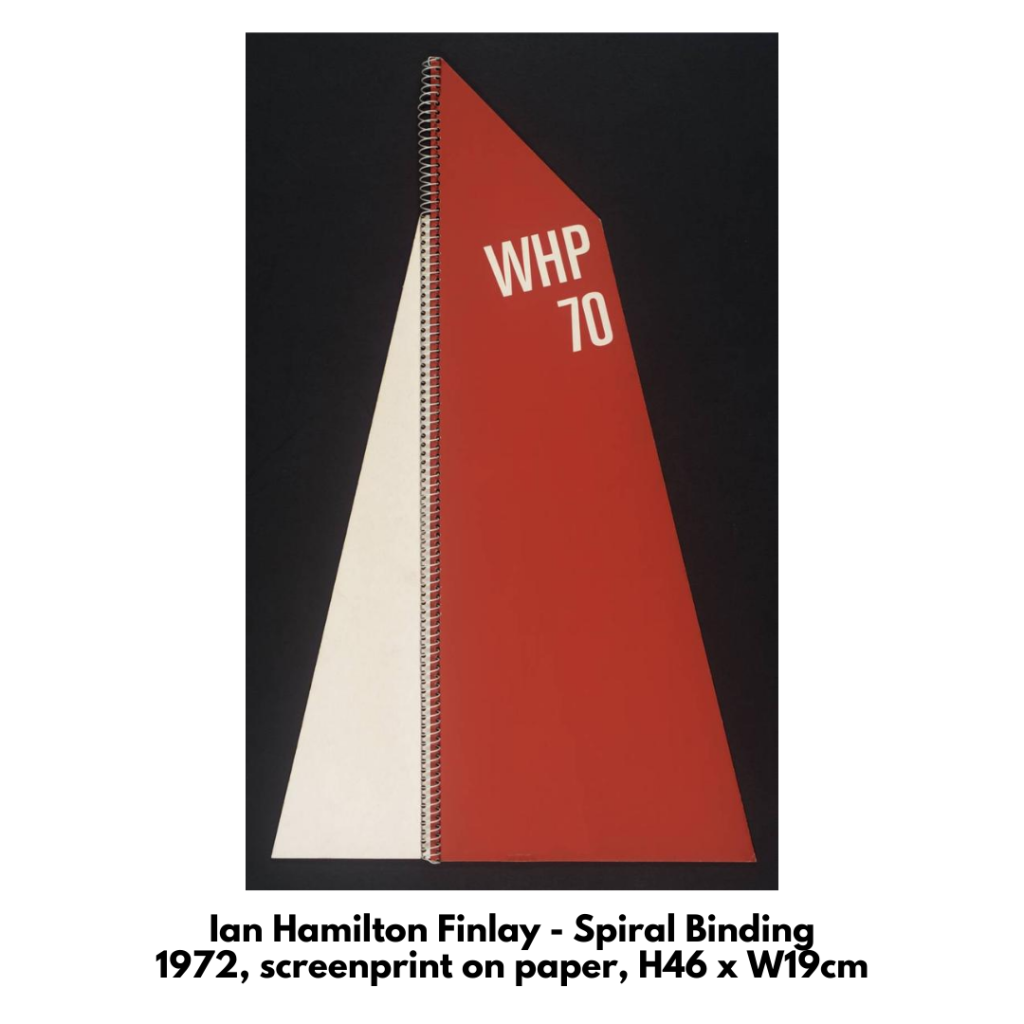

PRINT-MAKING:

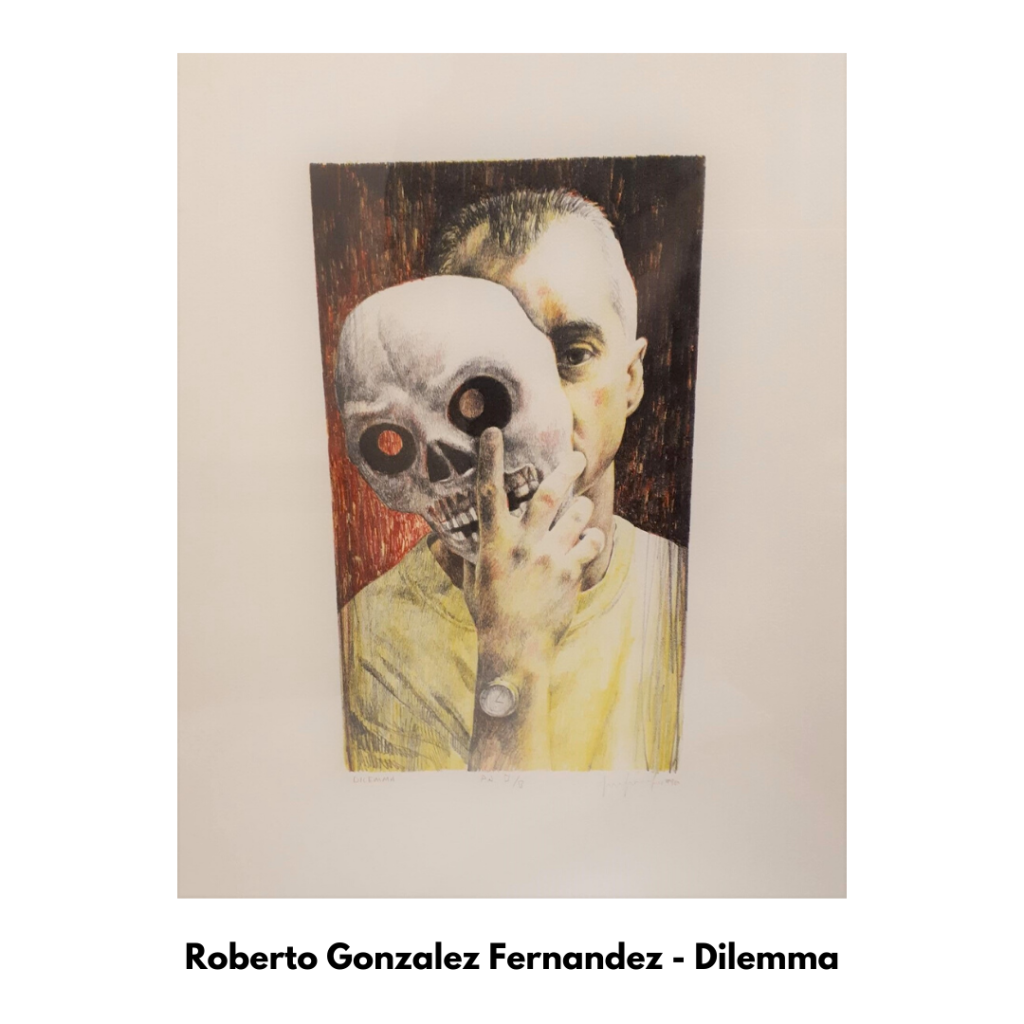

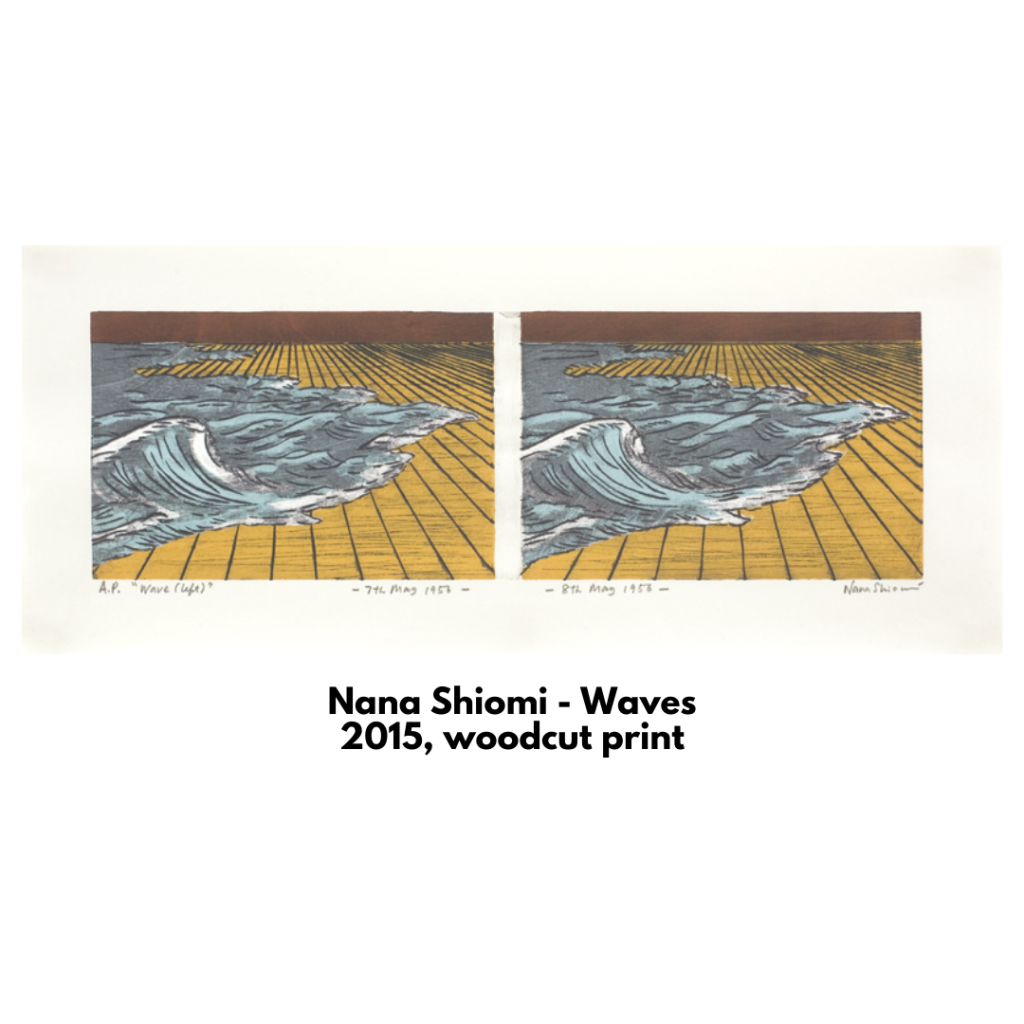

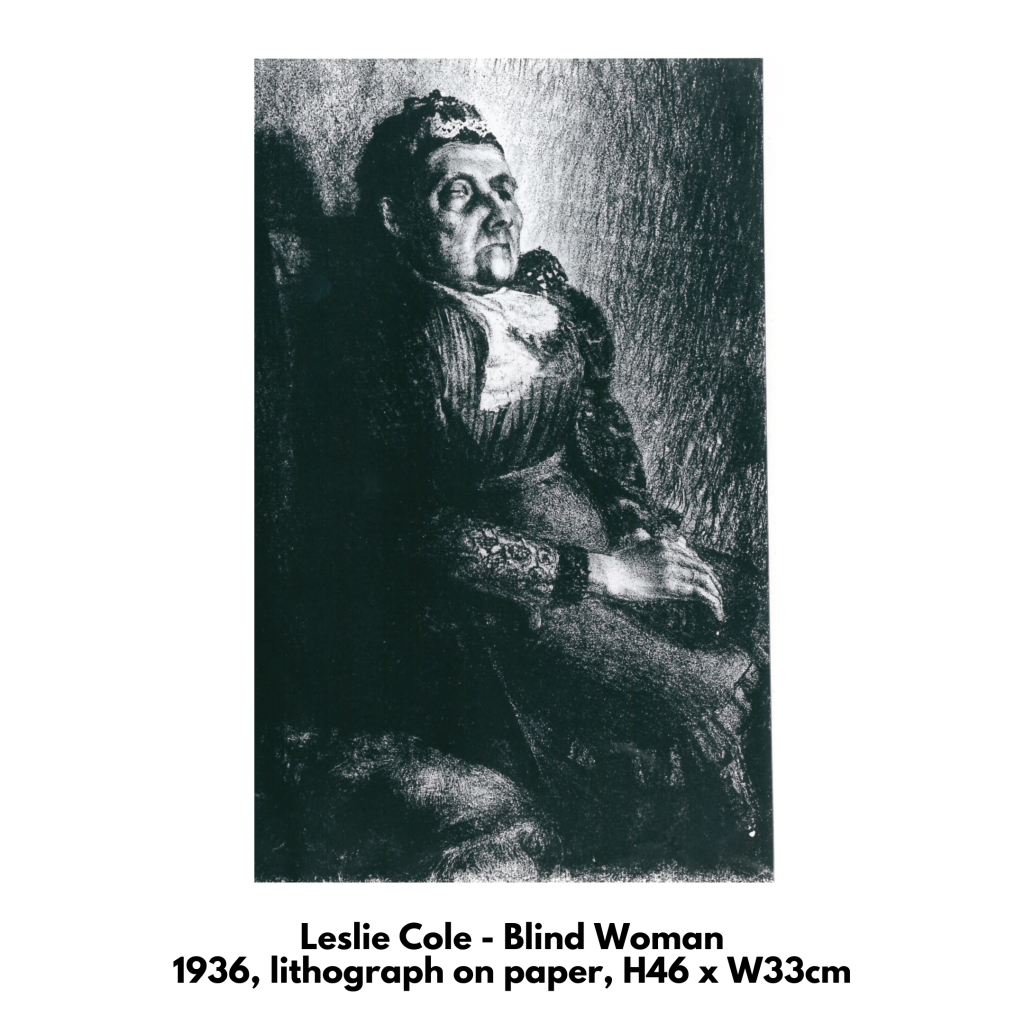

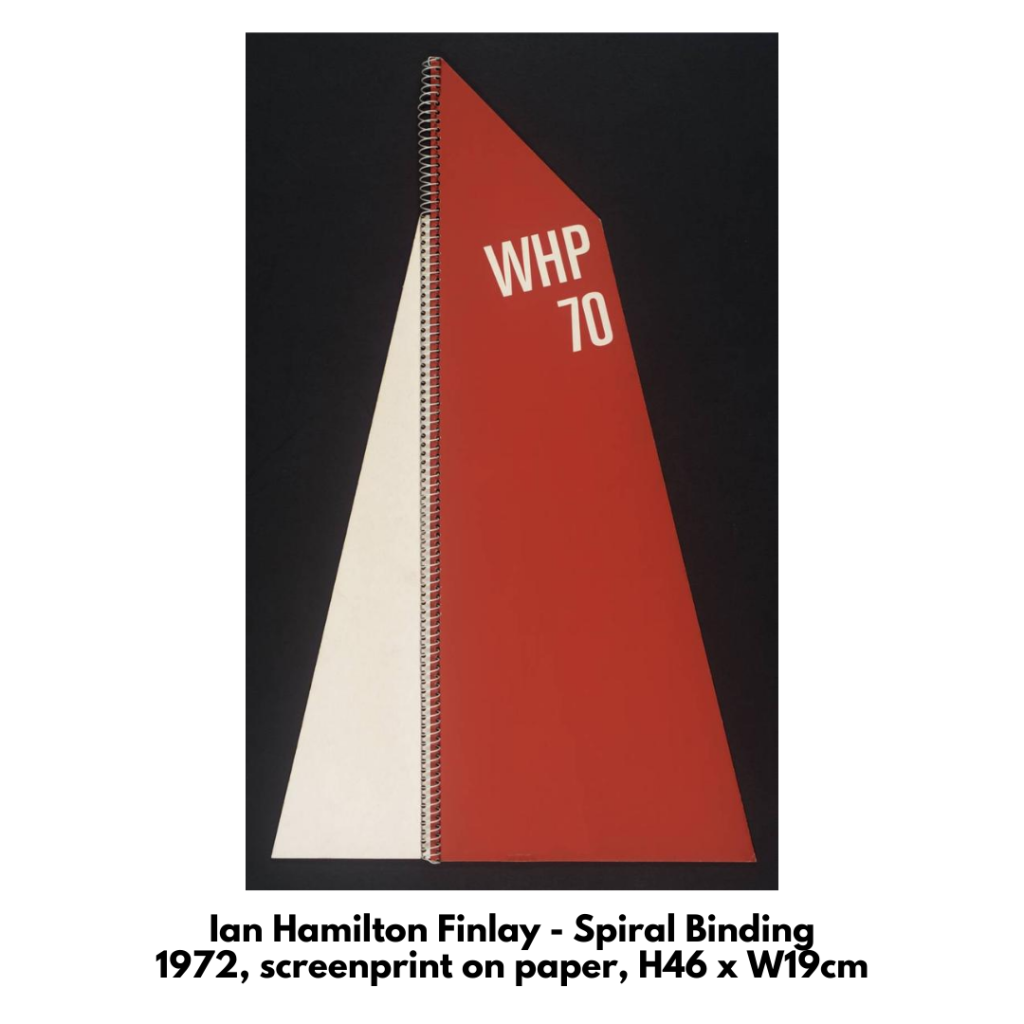

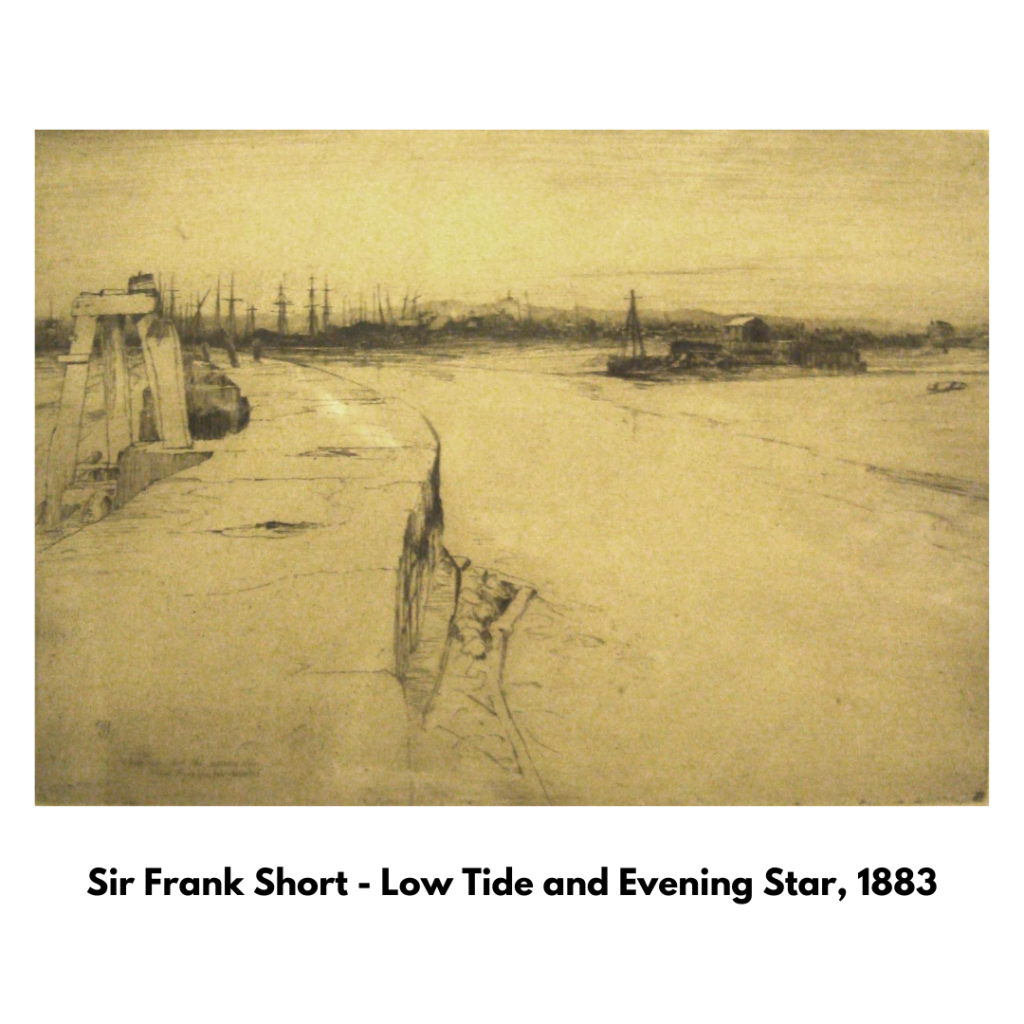

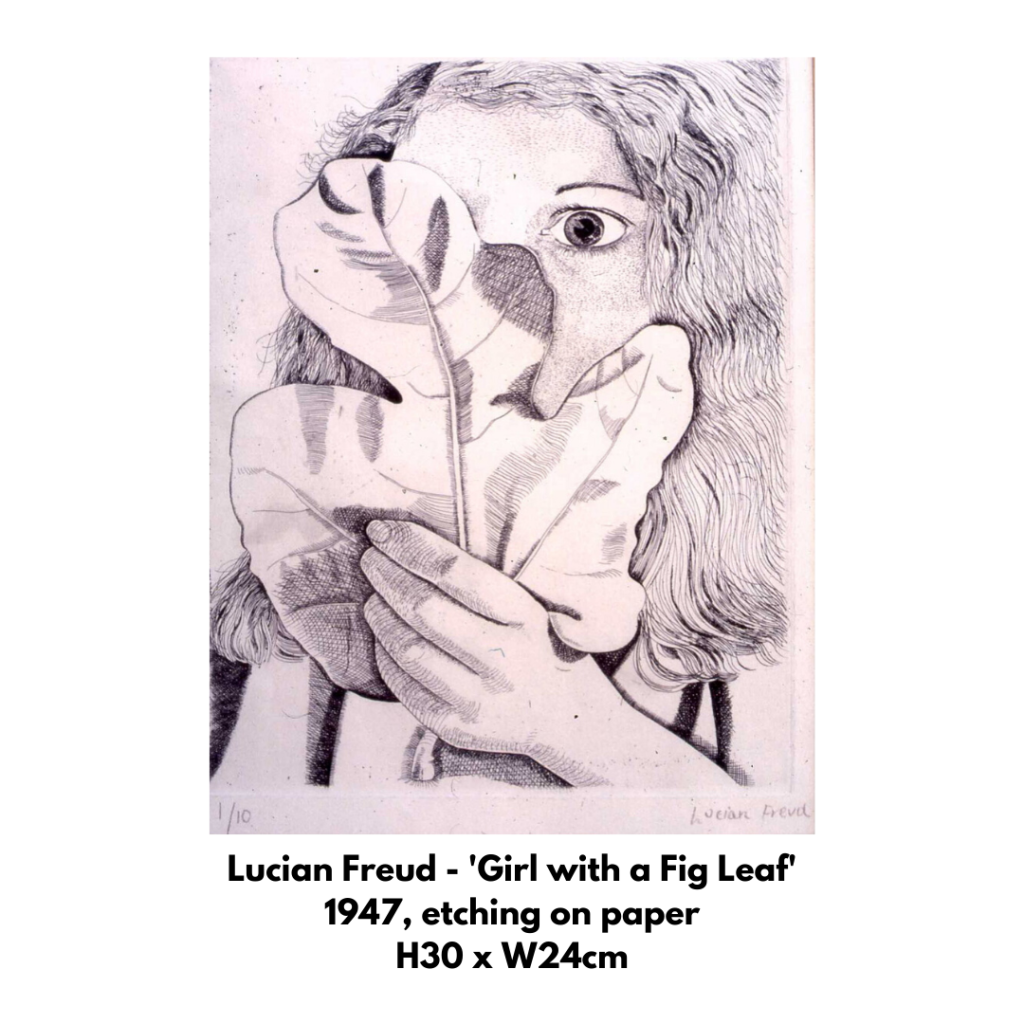

Printmaking is the process of transferring images from one surface to another. First created as a way of disseminating art to wider audiences, printing soon became an art in its own right, and everyone from Rembrandt (with his self-portrait etchings) to Warhol (with his Marilyn Monroe screenprints) has jumped on the bandwagon since! Printmaking includes etching, engraving, lithography, woodcut and screenprinting. Contemporary printmaking may also include digital printing and photographic mediums.

First, artists create a matrix, or template, from a material like wood, metal, plastic, linoleum or glass. The design is created on the matrix by working its flat surface with either tools or chemicals. The matrix is then inked in order to transfer the image onto the final surface – often paper or fabric. The final print is a mirror image of the original design. One of the benefits of printmaking is that artists are able to create many impressions of the same design. Prints are considered to be original, unique artworks, even when there is more than one of the same image, so are referred to as ‘impressions’, rather than ‘copies’.

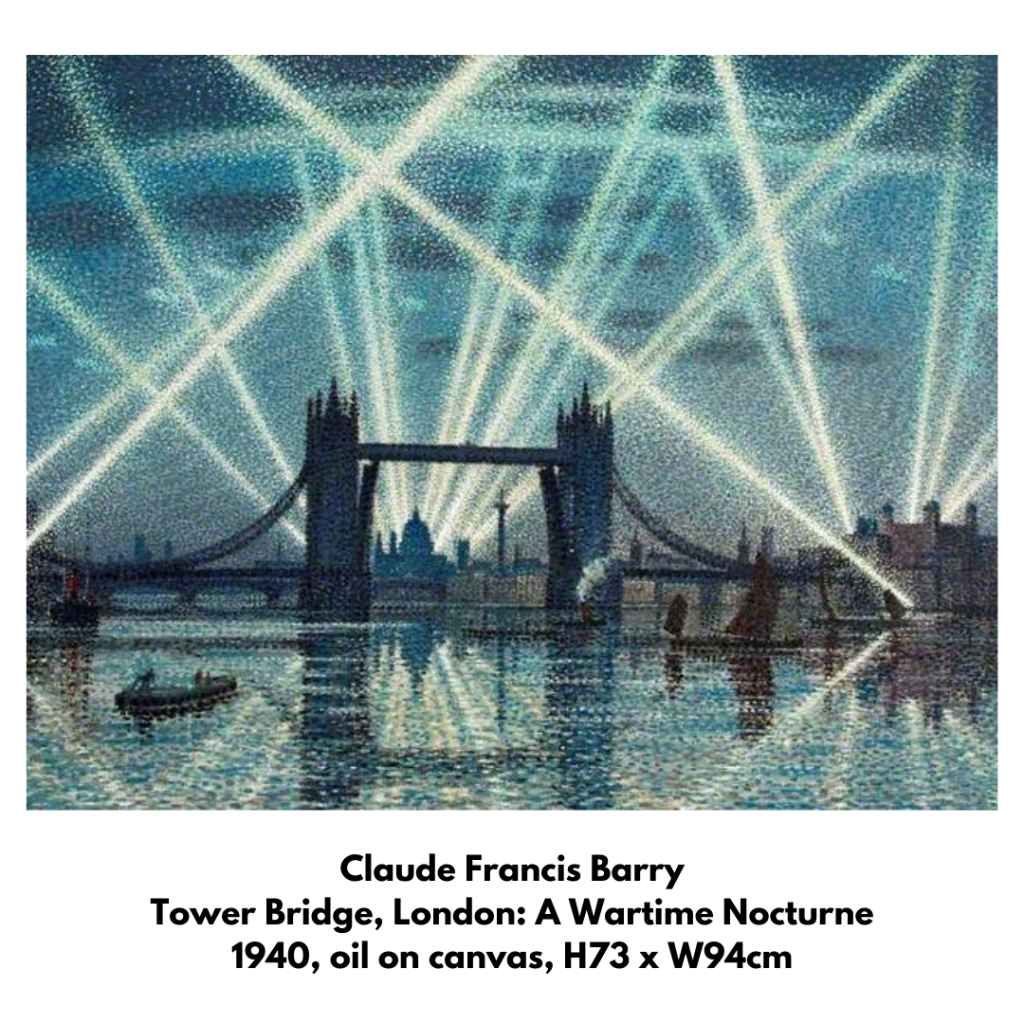

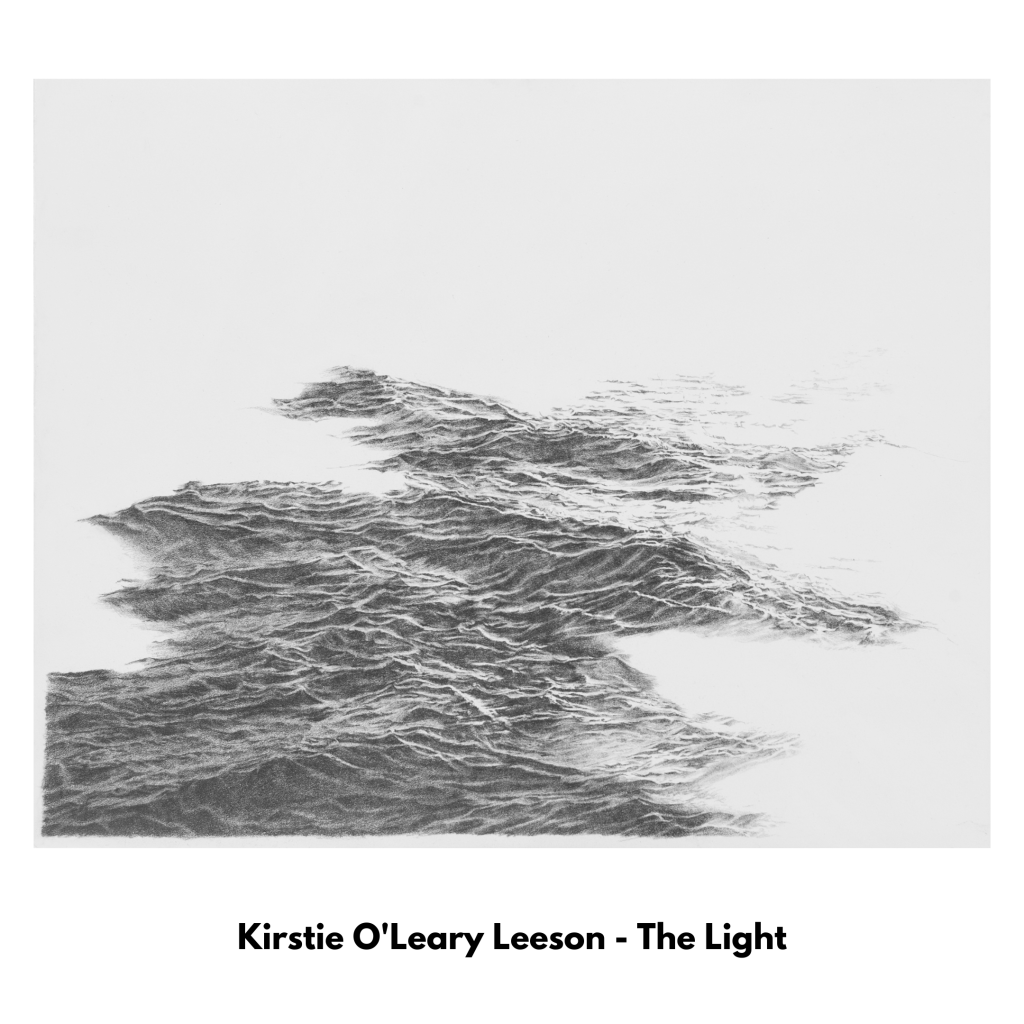

LIGHT:

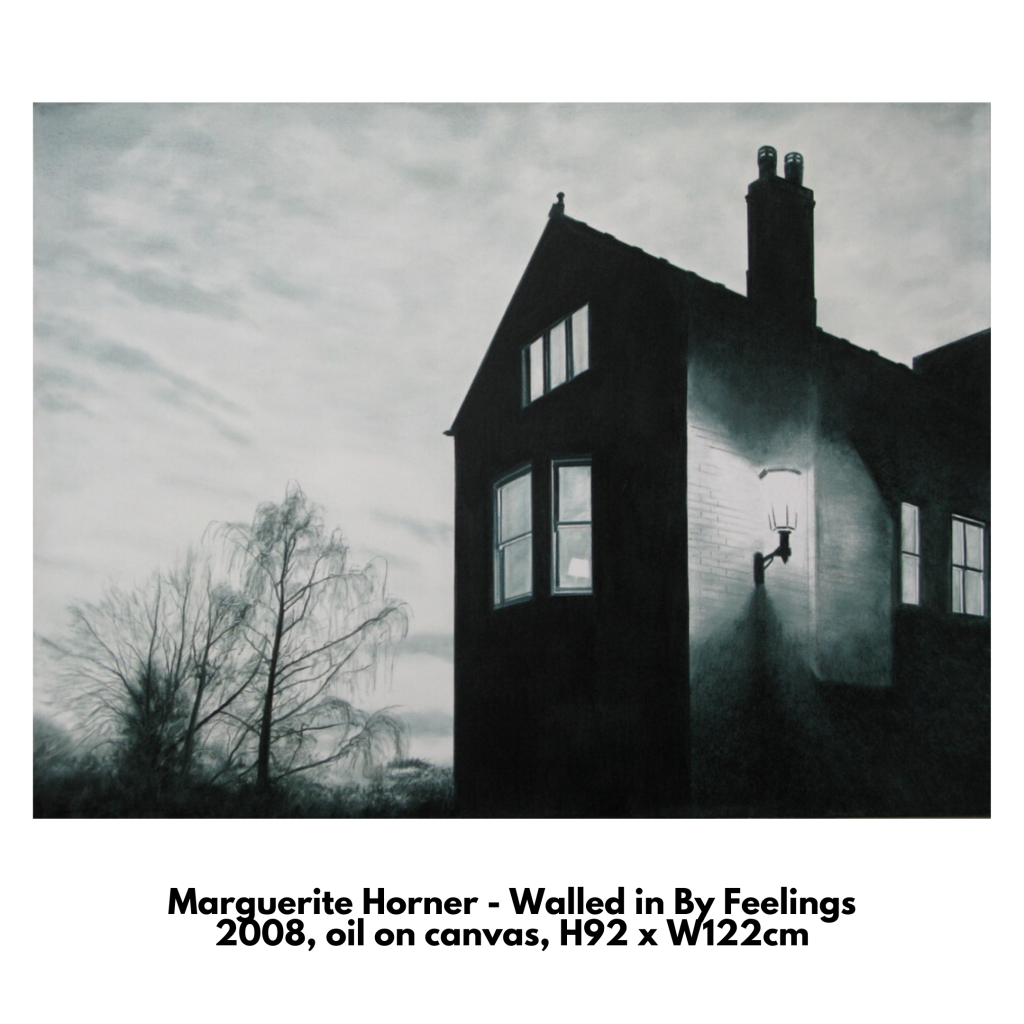

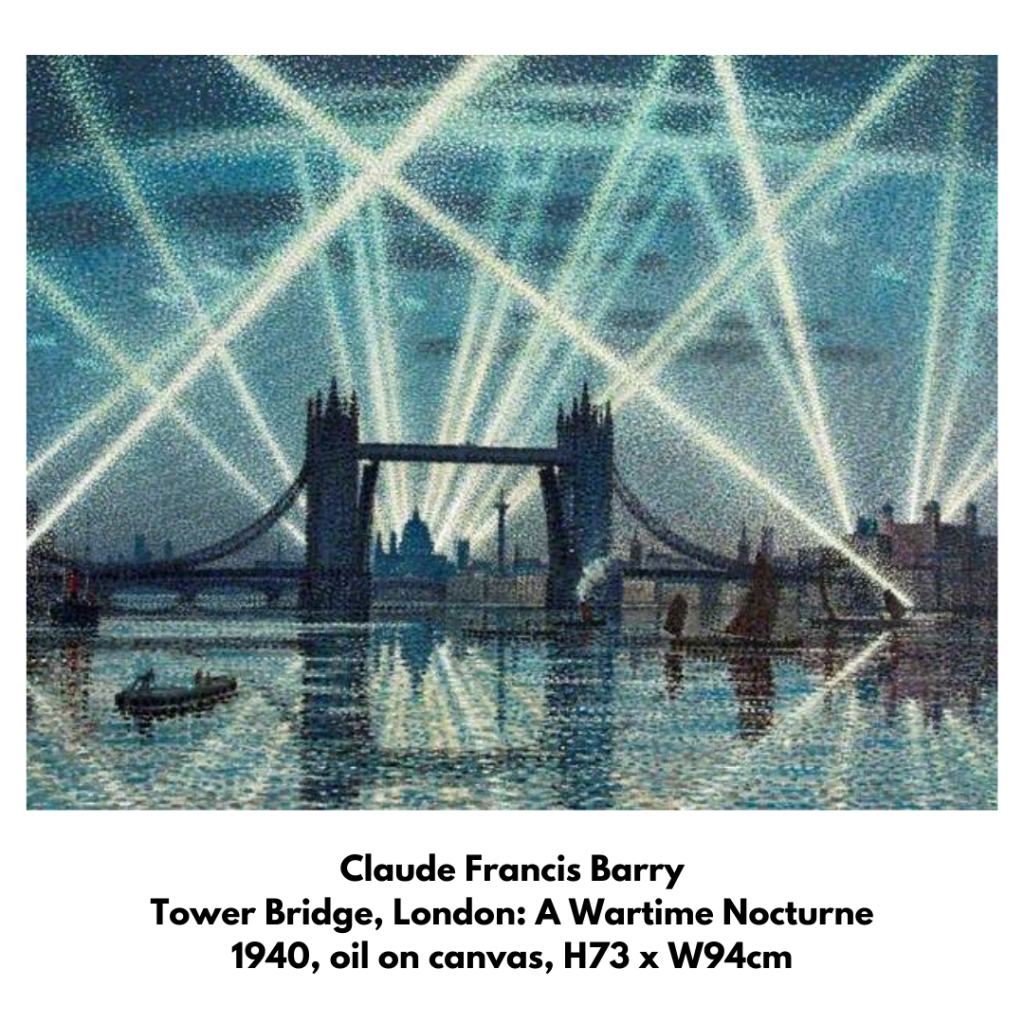

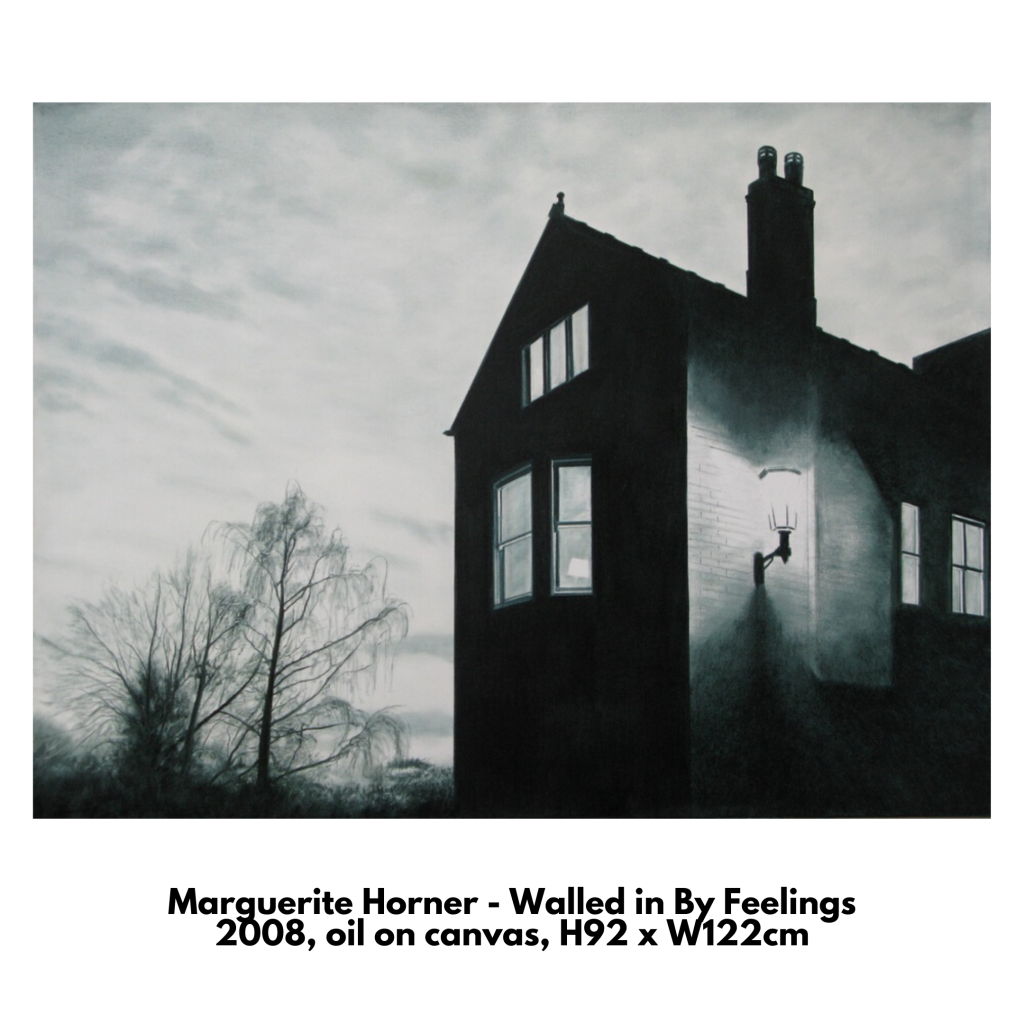

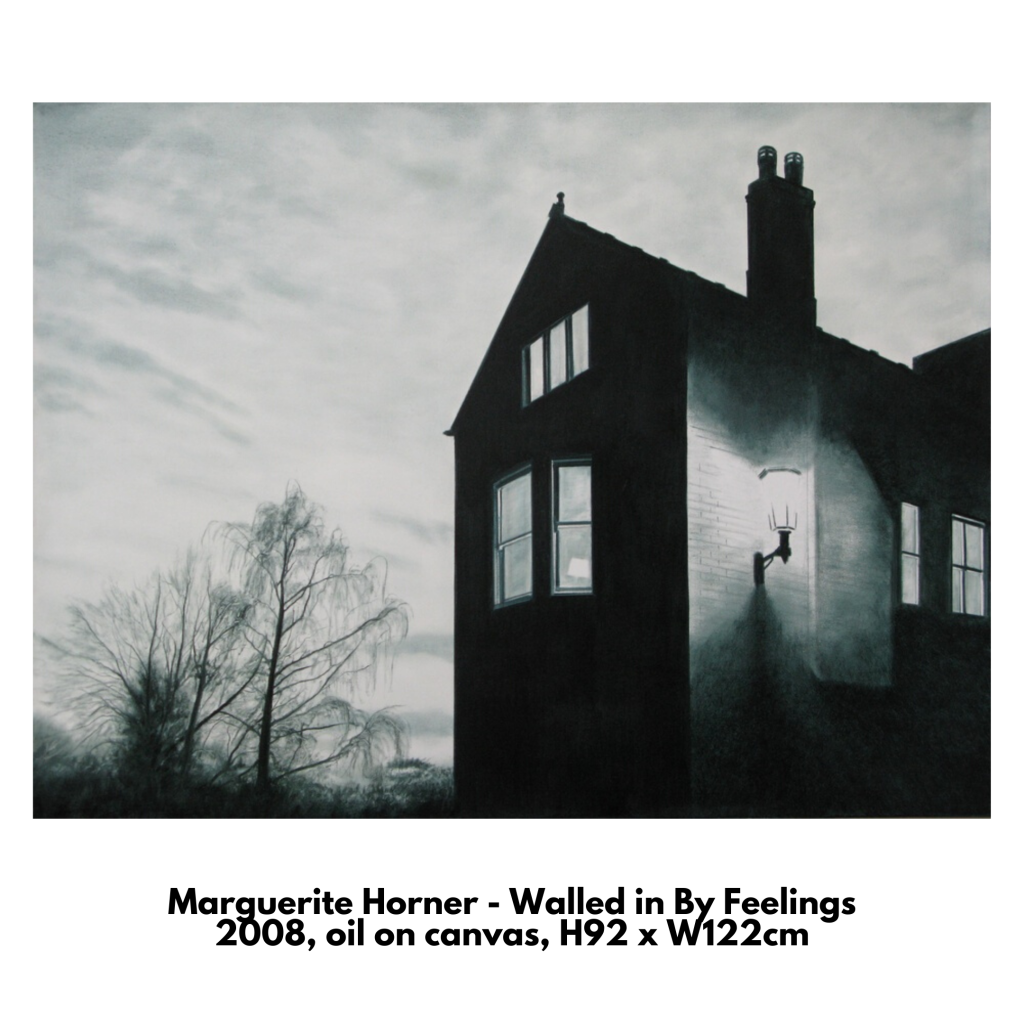

Throughout history, artists have recognised the power of light to transform our experience of an artwork. After all, light is integral to sight. It surrounds us and impacts everything we see. It can determine the way we feel, what we do, and the way we view our surroundings. For hundreds of years, artists have been manipulating light for dramatic effect to tell stories and heighten emotional impact.

Scientific explorations of light and colour in the 17th Century led some artists to focus more intently on light as a subject matter in itself. In the 19th Century, the controversial Impressionist artists explored the ephemeral effects of light in nature, developing techniques which are still fundamental to the way many artists work today. In recent years, some artists have used light and dark to create optical illusions, and emphasise forms and patterns. Meanwhile the art of photography controls and manipulates light itself, to record a person, object or landscape at just the click of a button.

THE TURNER-PRIZE:

The Turner Prize is an art prize of £25,000, presented annually to a British visual artist (plus £5000 for each of four short-listed artists). The prize is organised by The Tate Gallery and usually staged at Tate Britain. It was first awarded in 1984, includes all forms of media, and has its roots in conceptual art. Artists are chosen based upon an exhibition of their work from the previous year.

The Prize is named after the English Romantic painter J.W.M Turner. Although Turner is now one of our most celebrated artists, often viewed as a ‘traditional’ landscape painter, during the early nineteenth century he was considered wildly controversial and his approach changed the course of art history. An apt name-sake for a prize that annually divides both the art establishment and the British public!

Often controversial for its choice of work, the Turner Prize is too close to the cutting edge of contemporary practice for some, and too far removed for others! It prompts conversations about the purpose, reach and definition of art. It has gained its place in the pantheon despite, or perhaps because of, the infamy of winning and short-listed artists like Damien Hirst with his tiger shark pickled in formaldehyde (The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991), and Tracey Emin with her famously unkempt bed (My Bed, 1998).

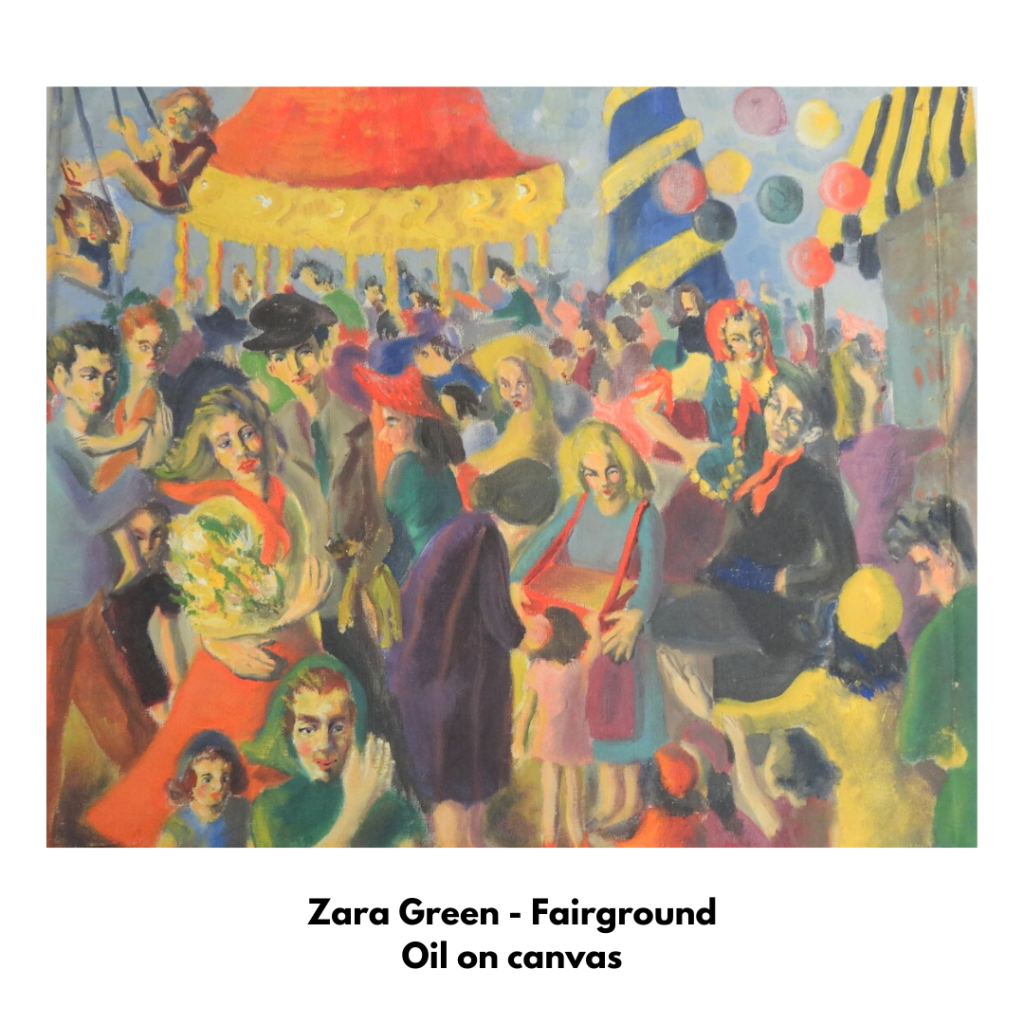

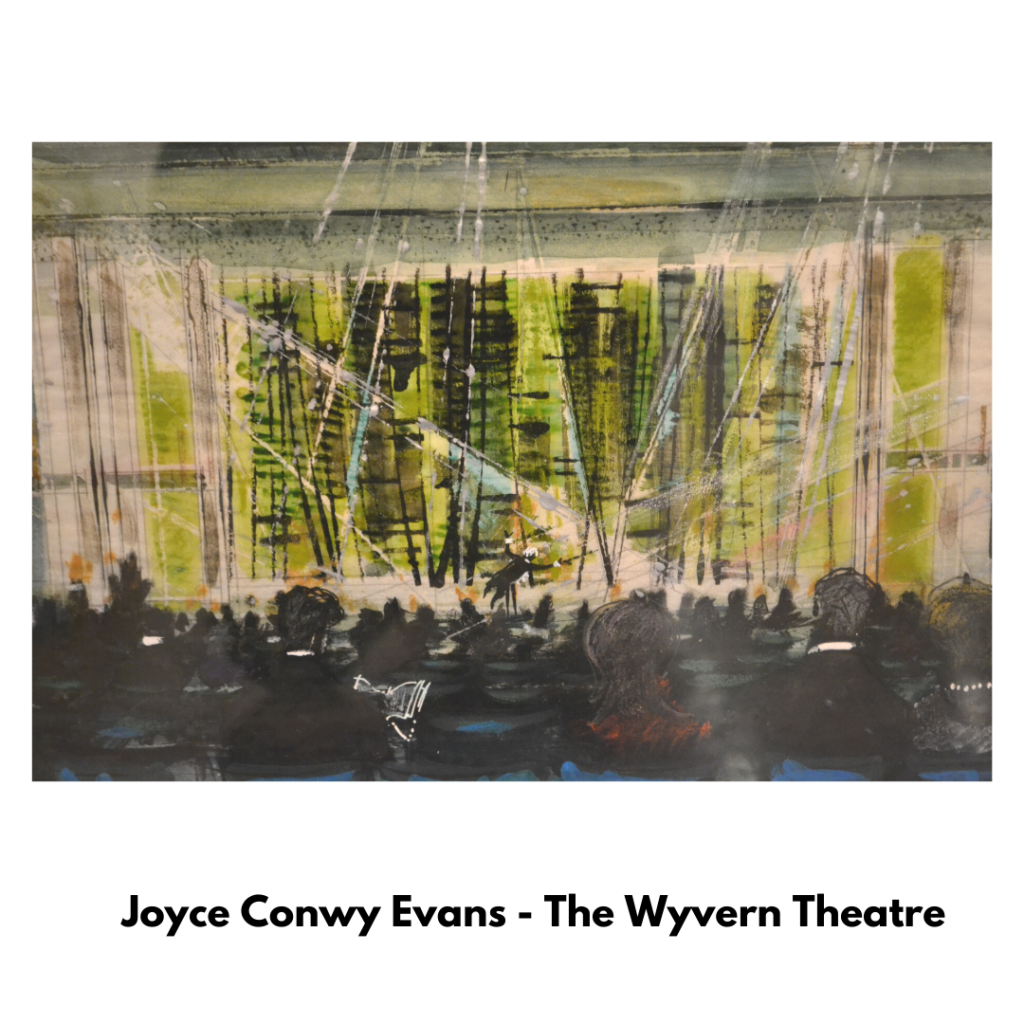

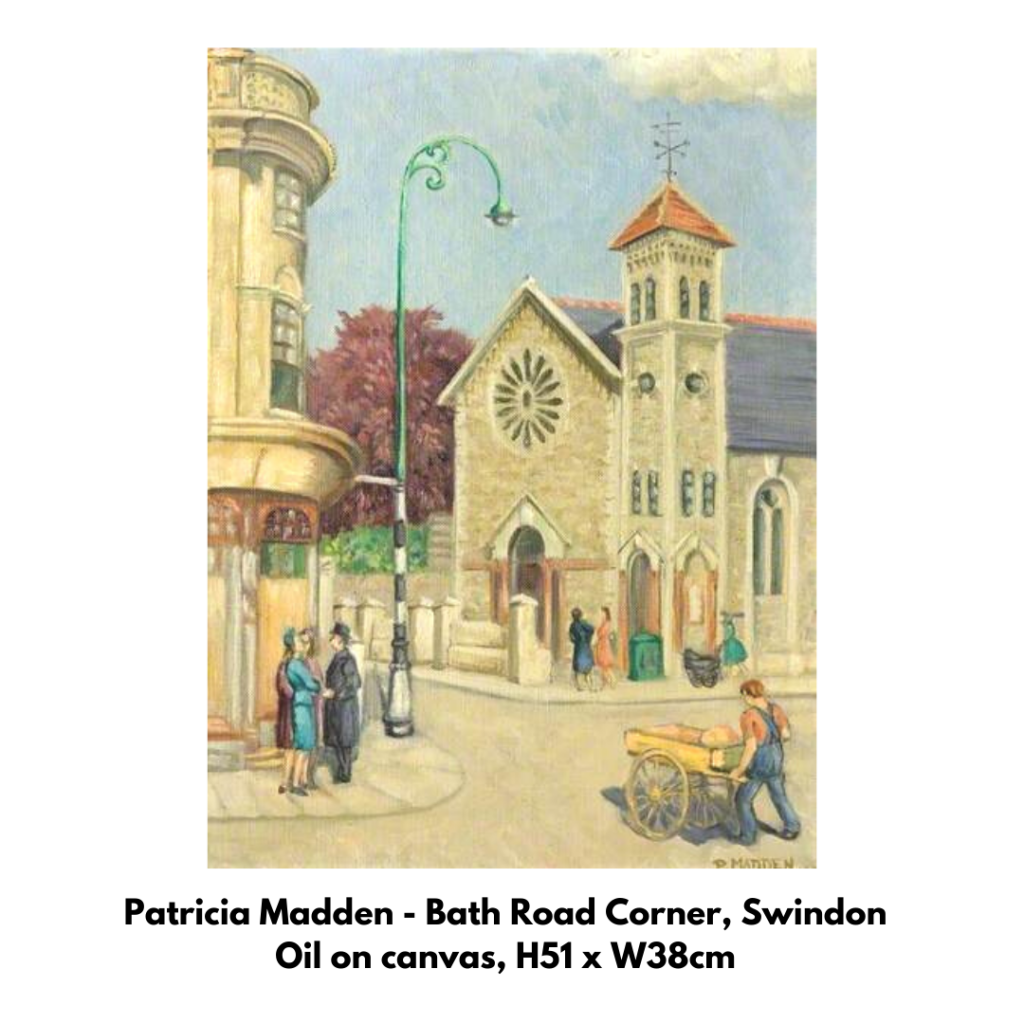

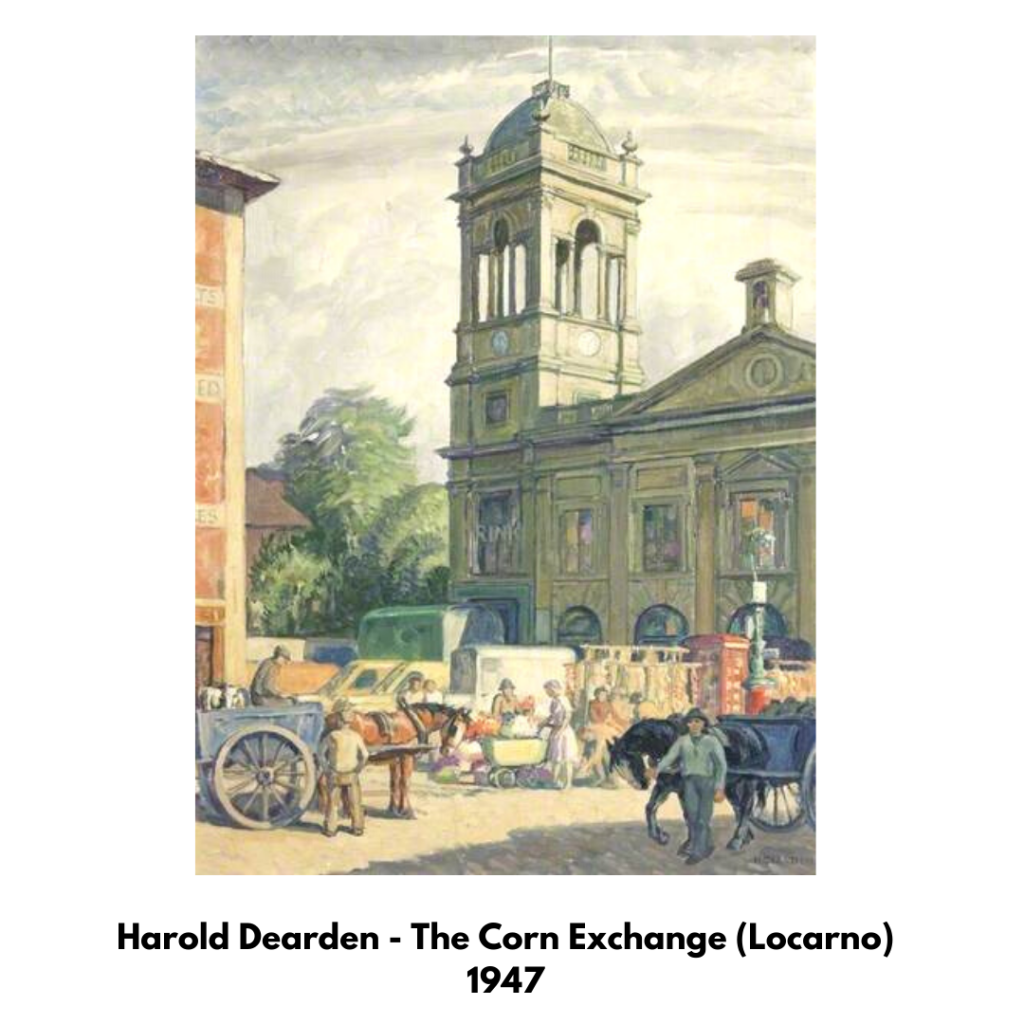

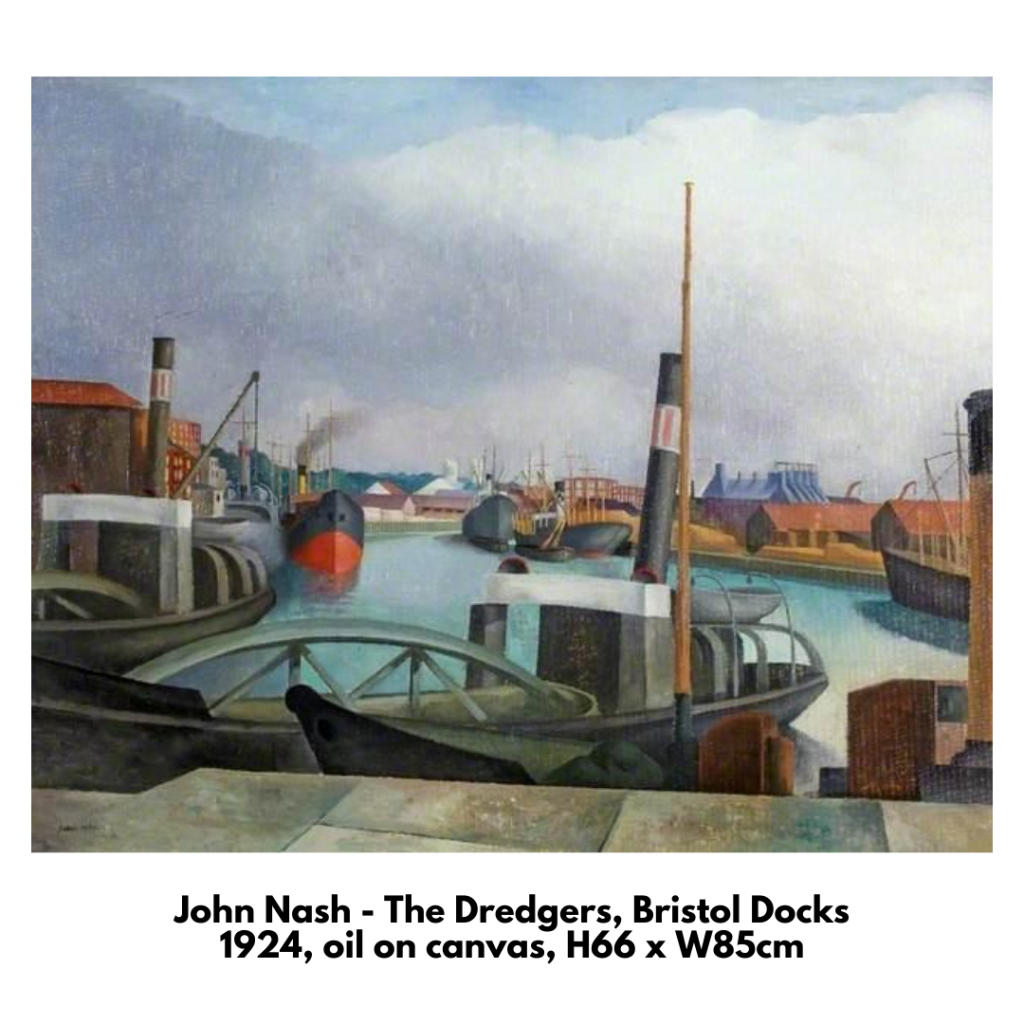

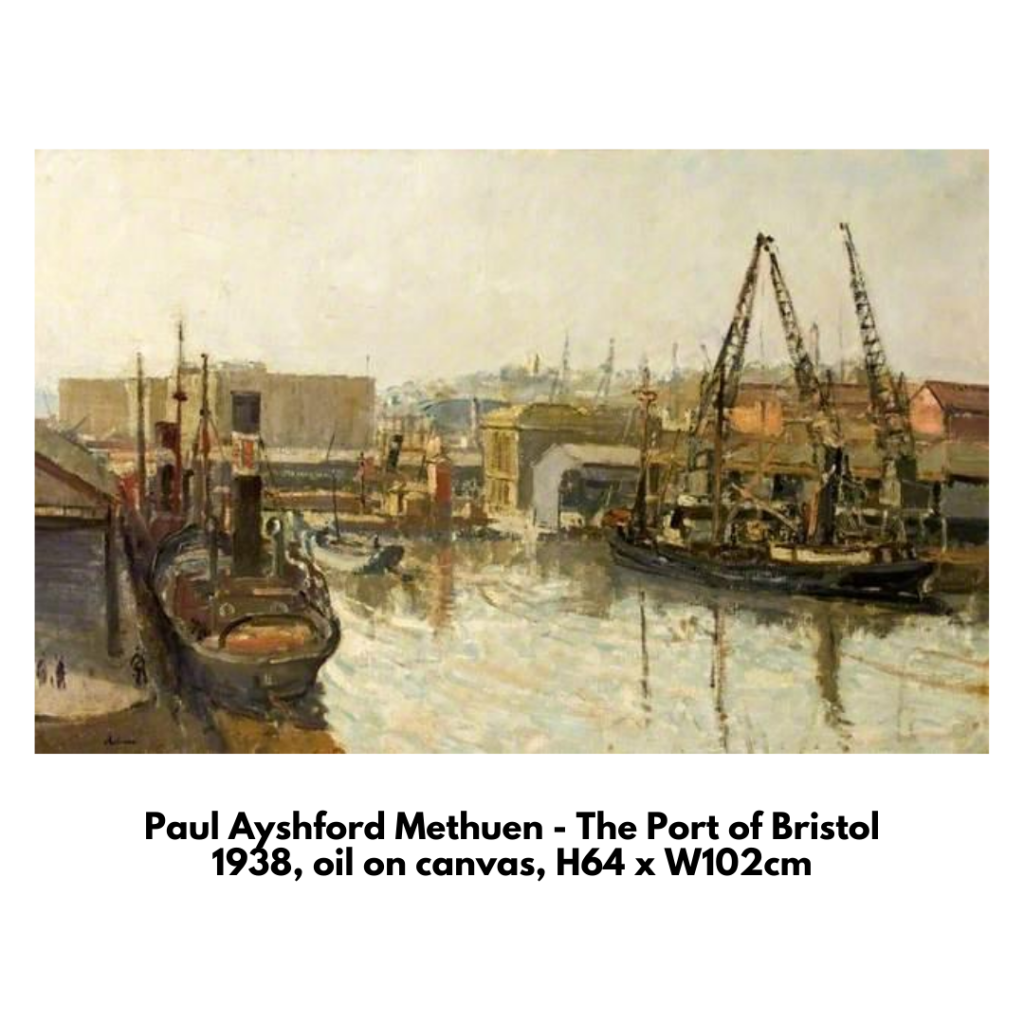

TOWNSCAPES:

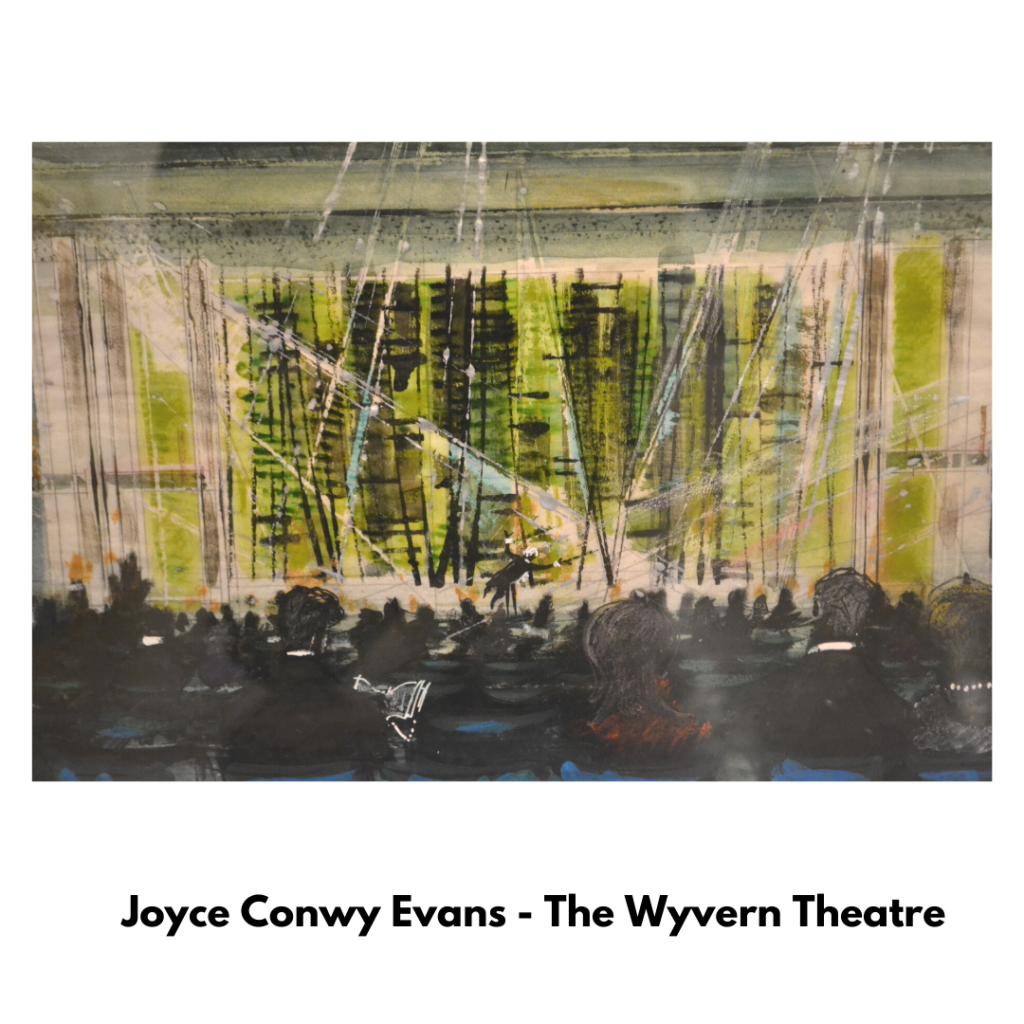

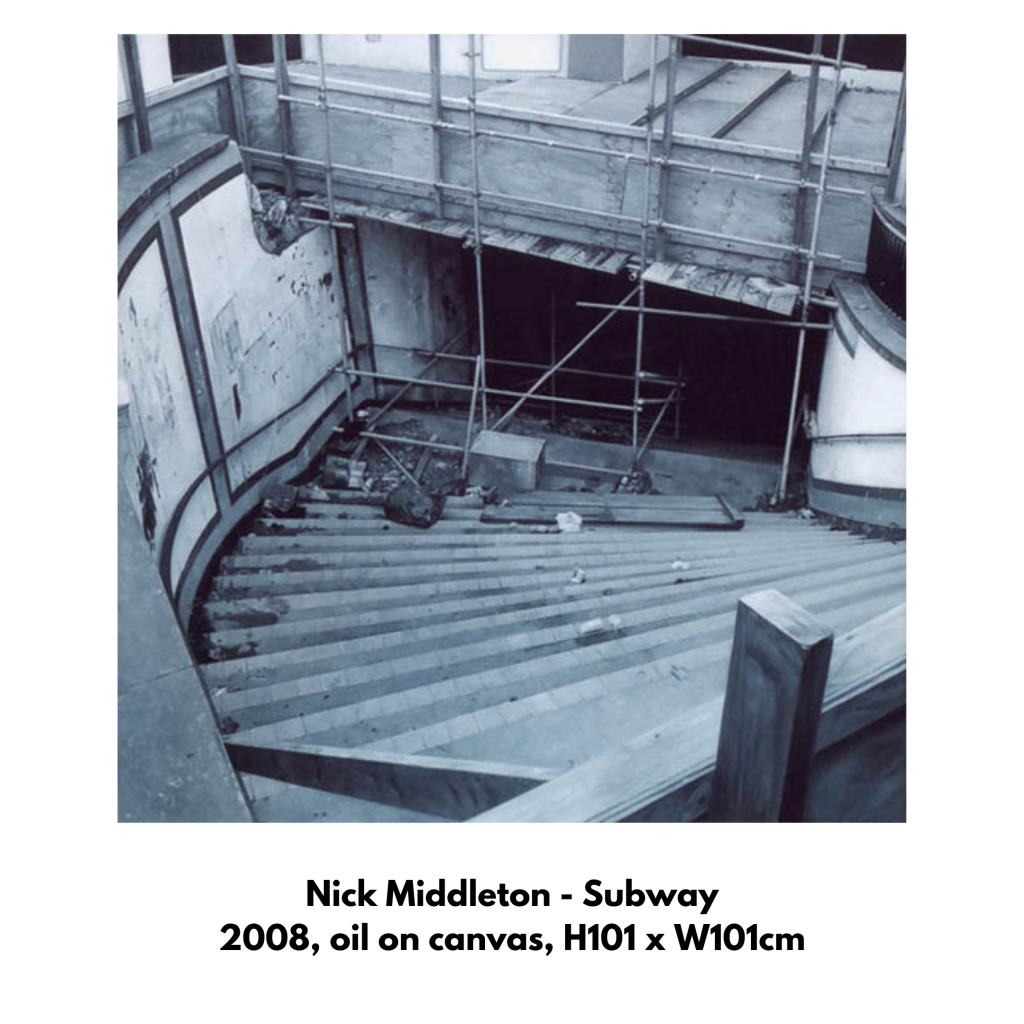

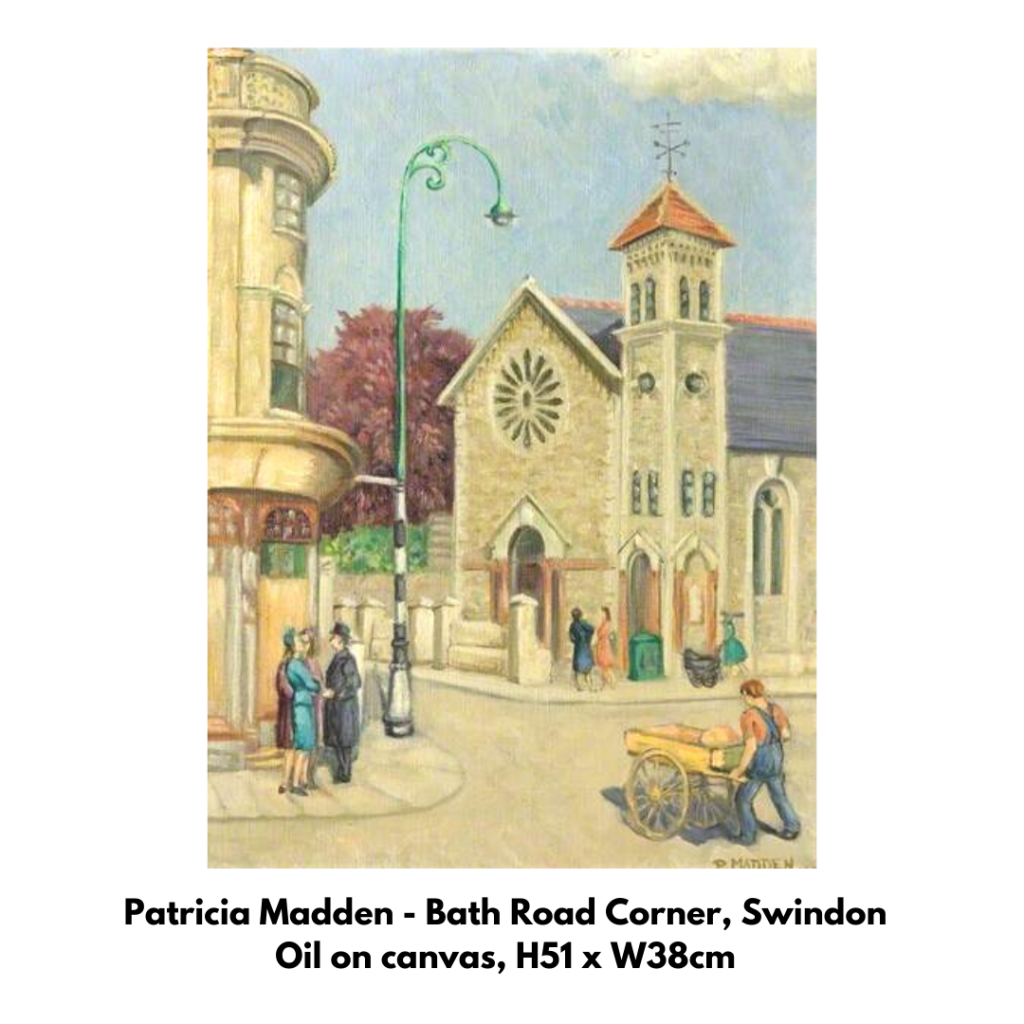

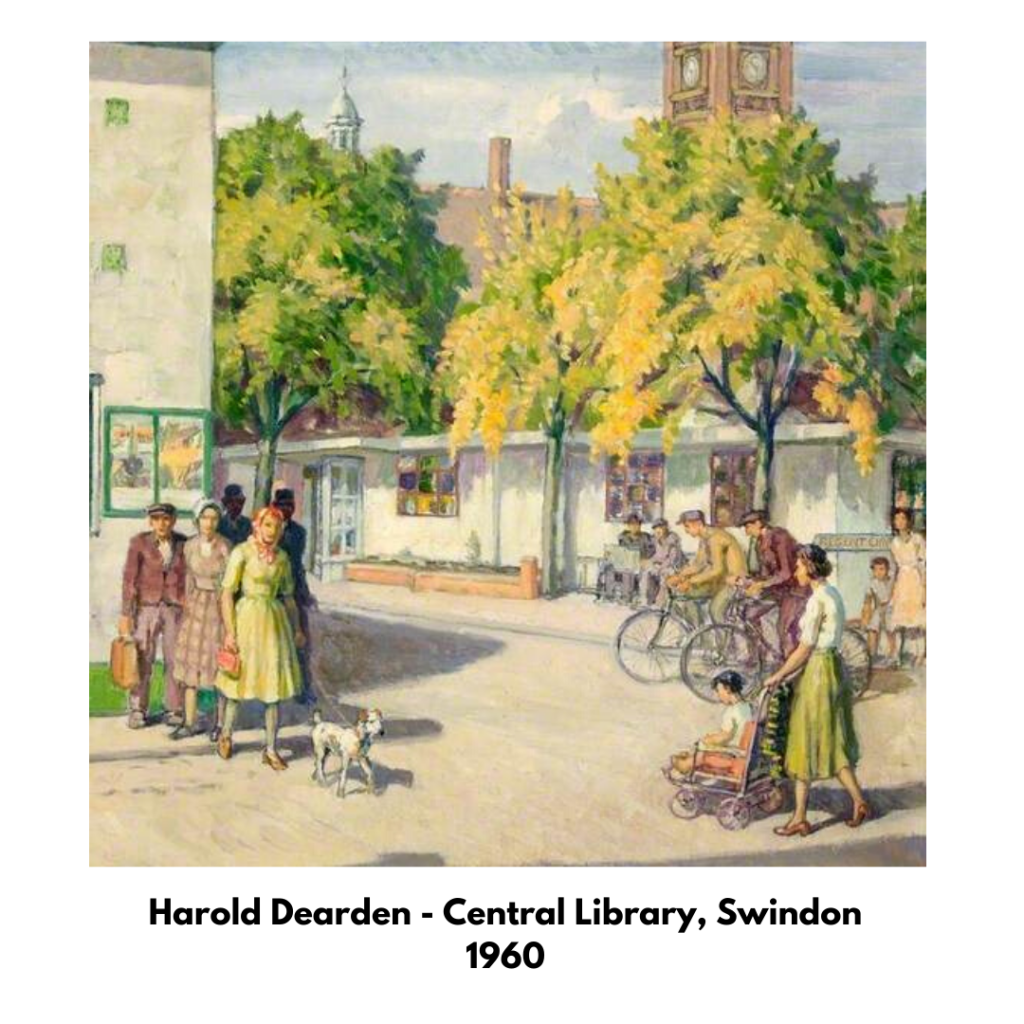

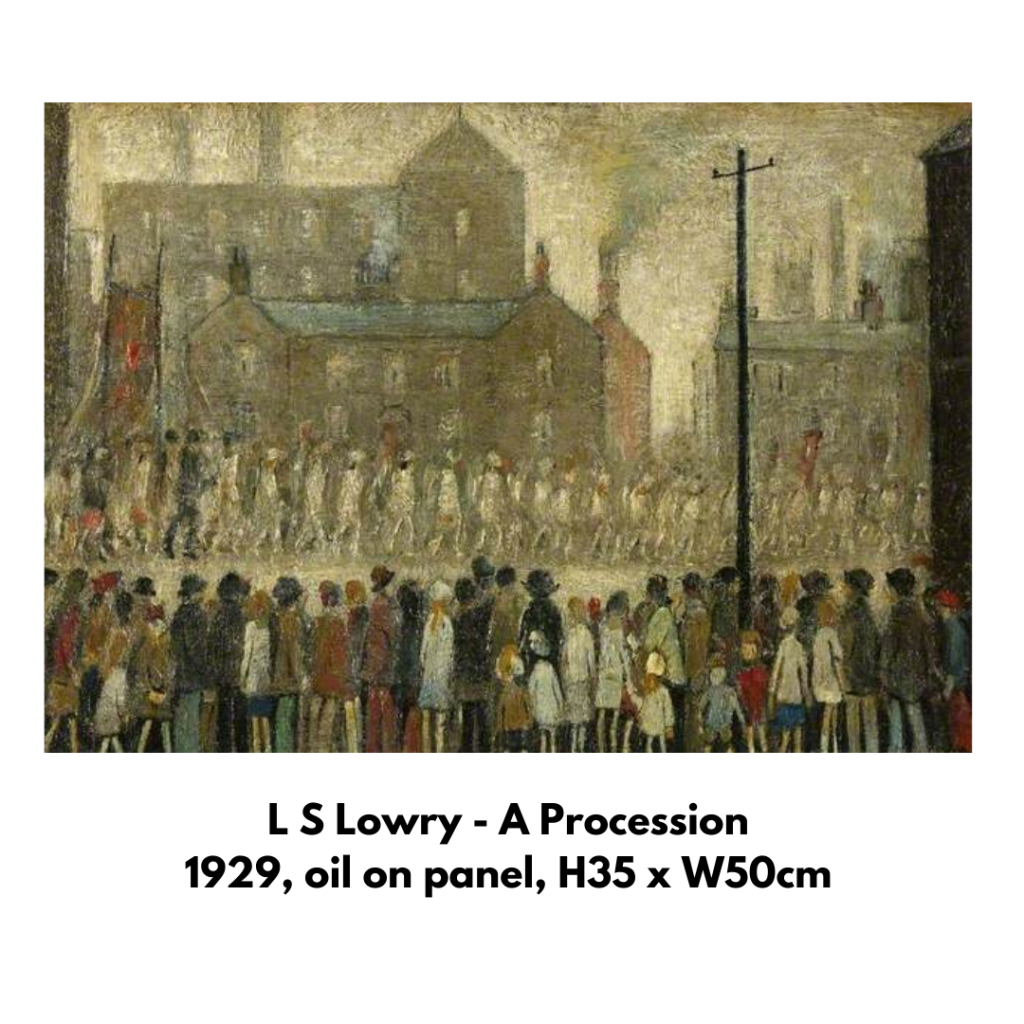

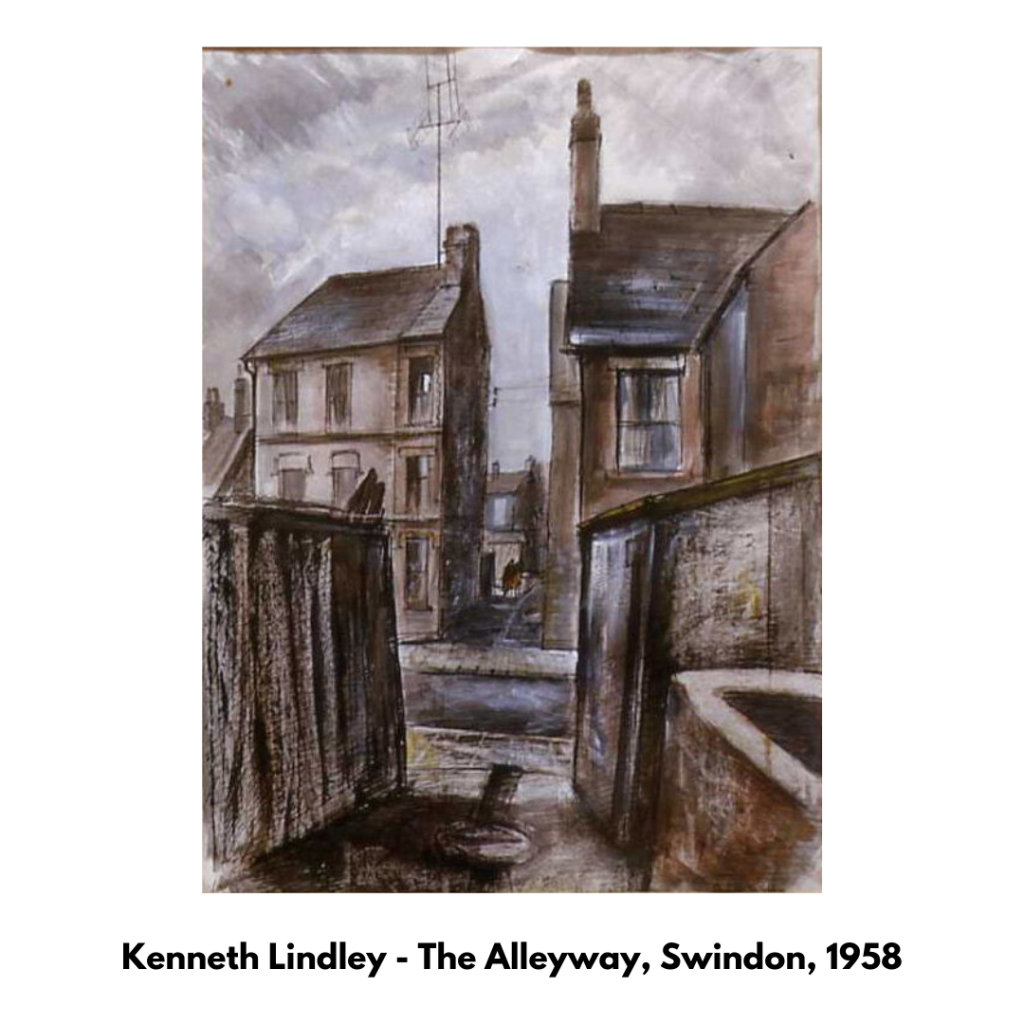

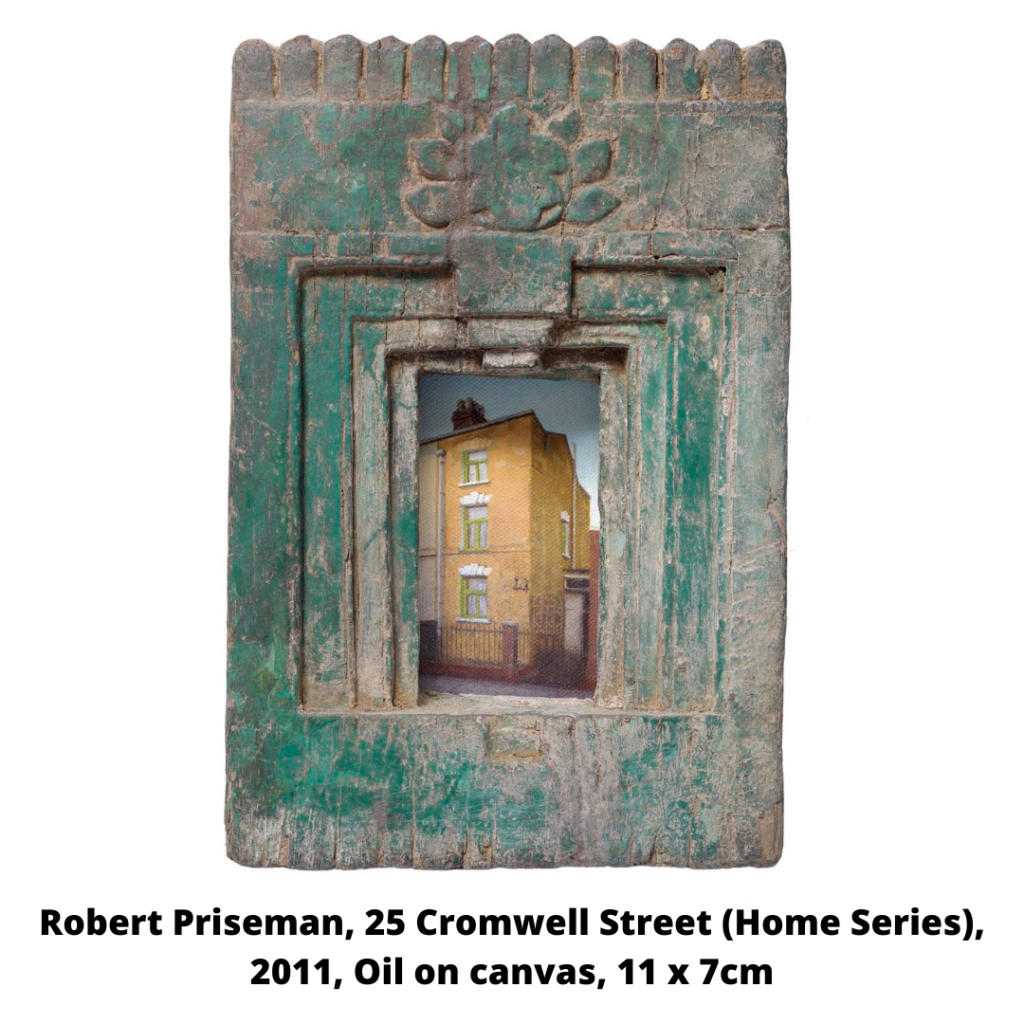

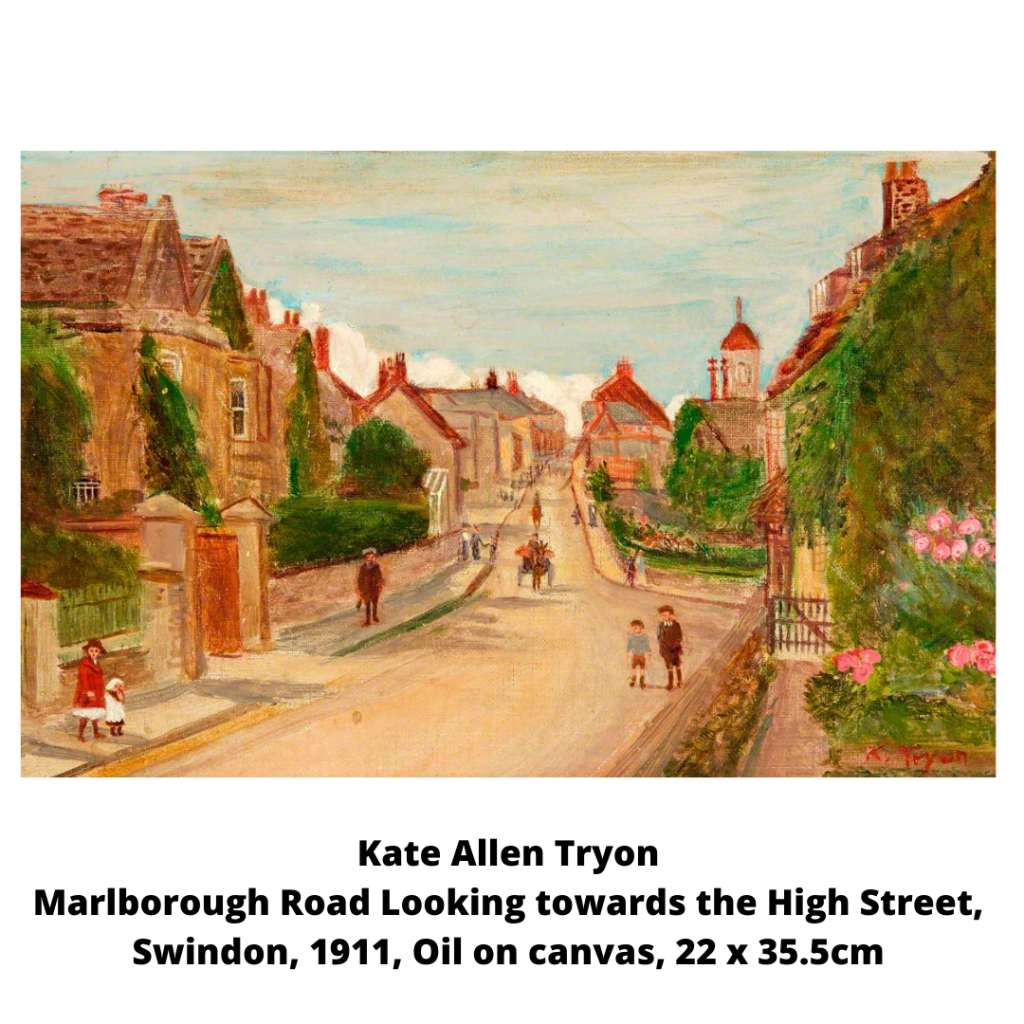

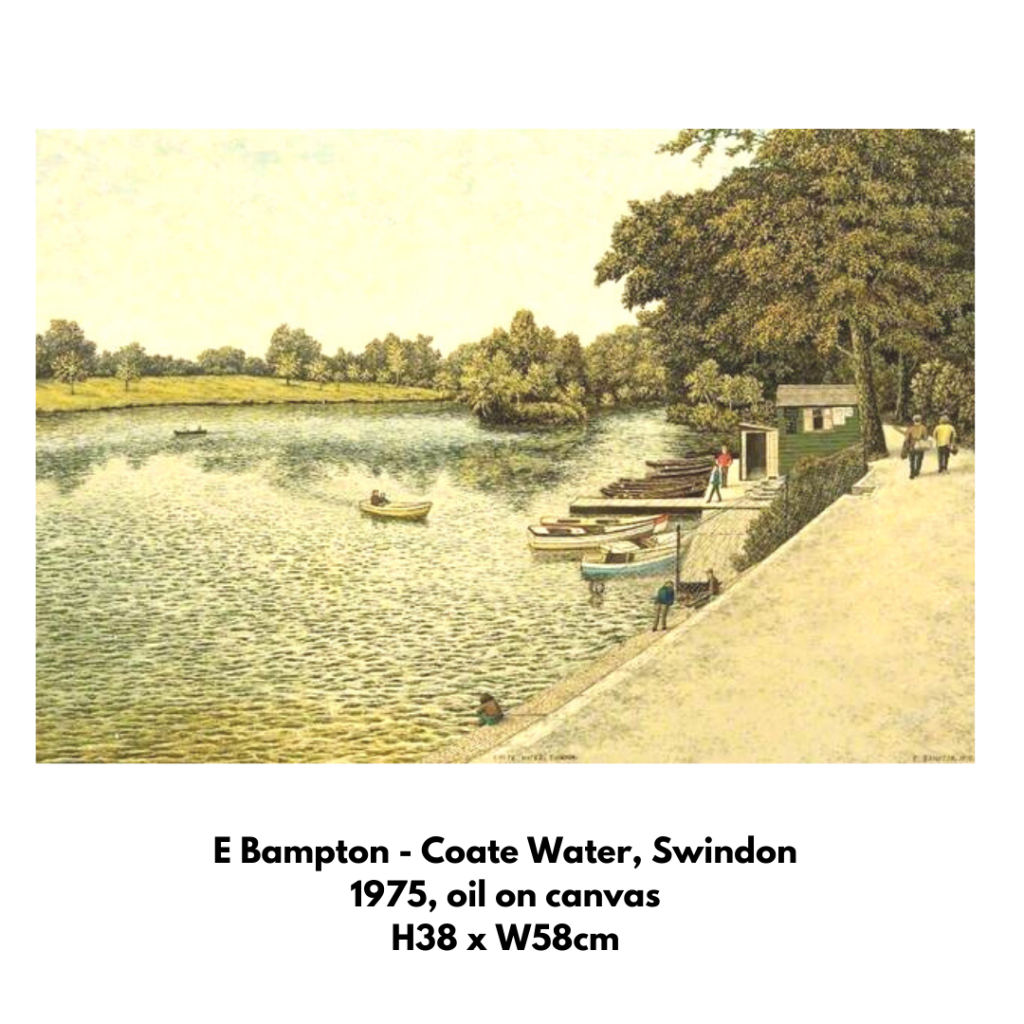

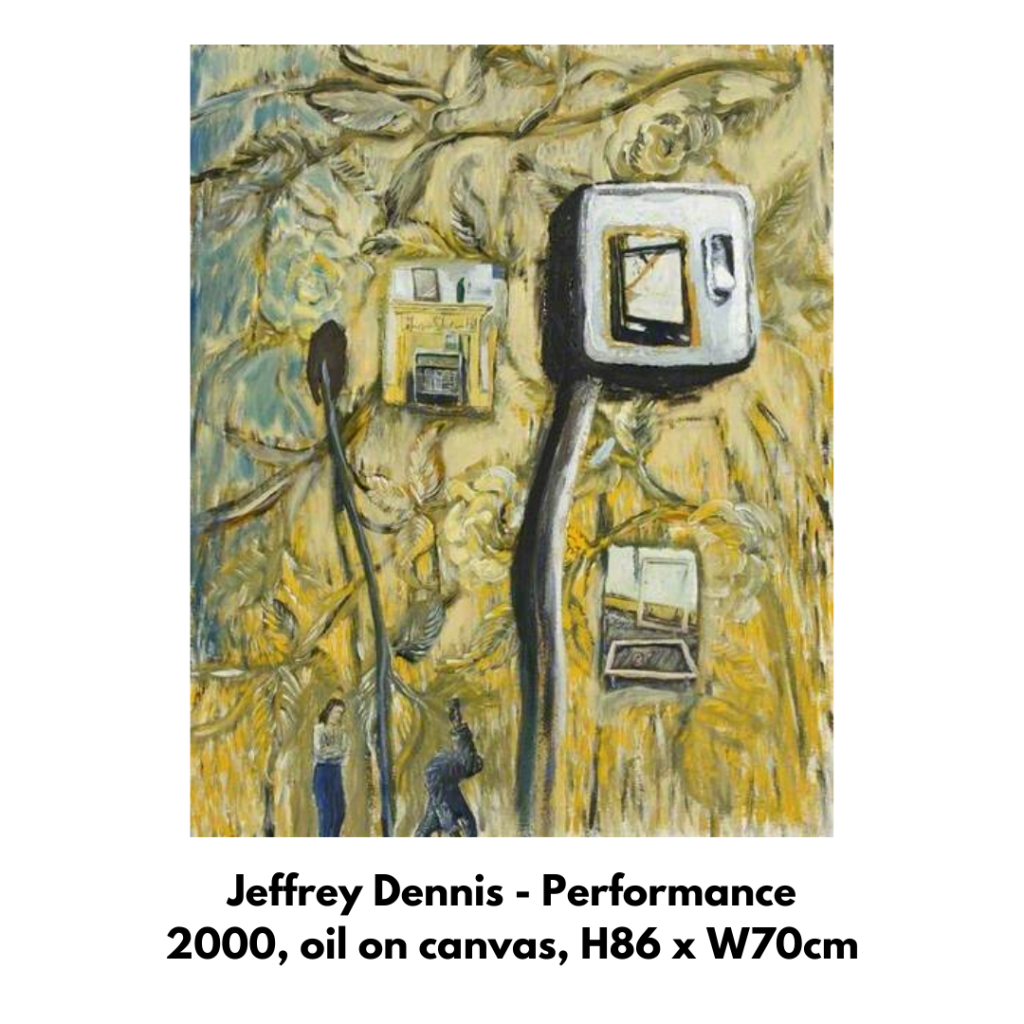

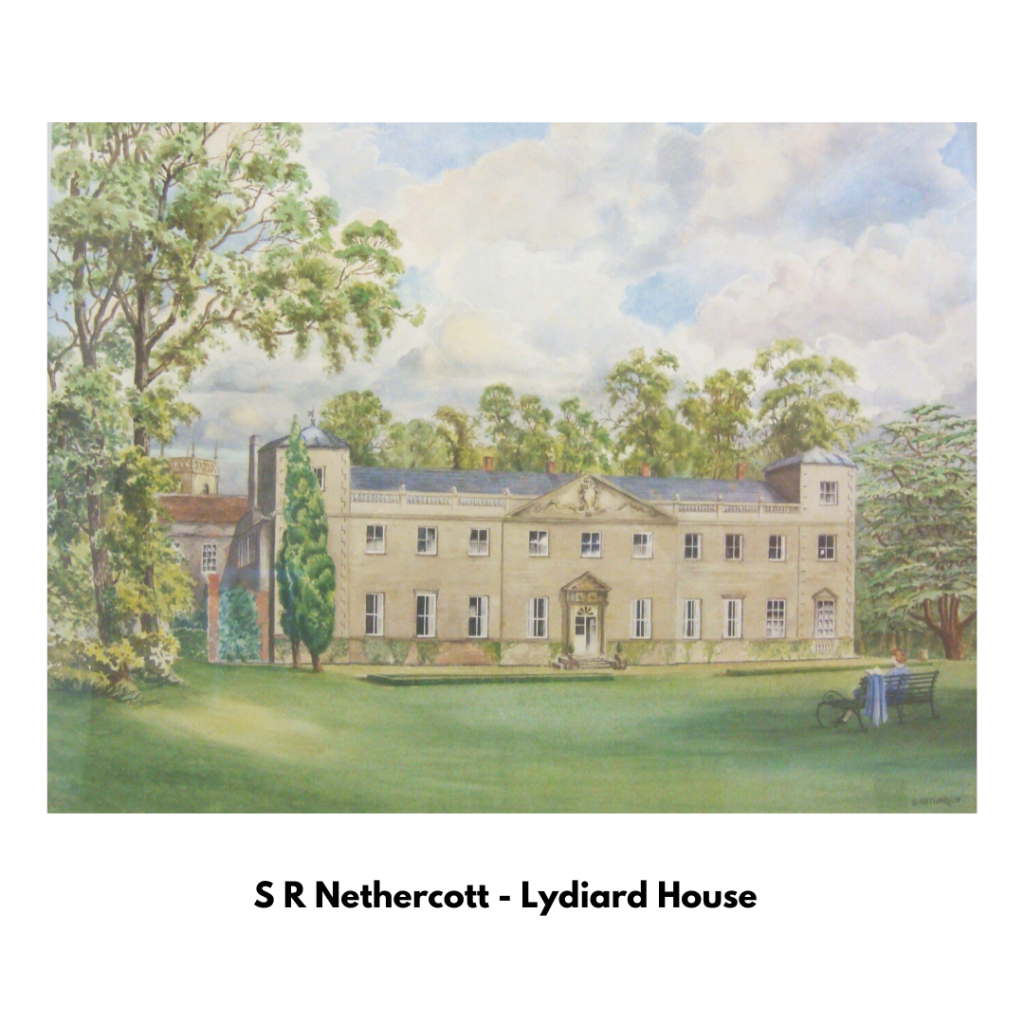

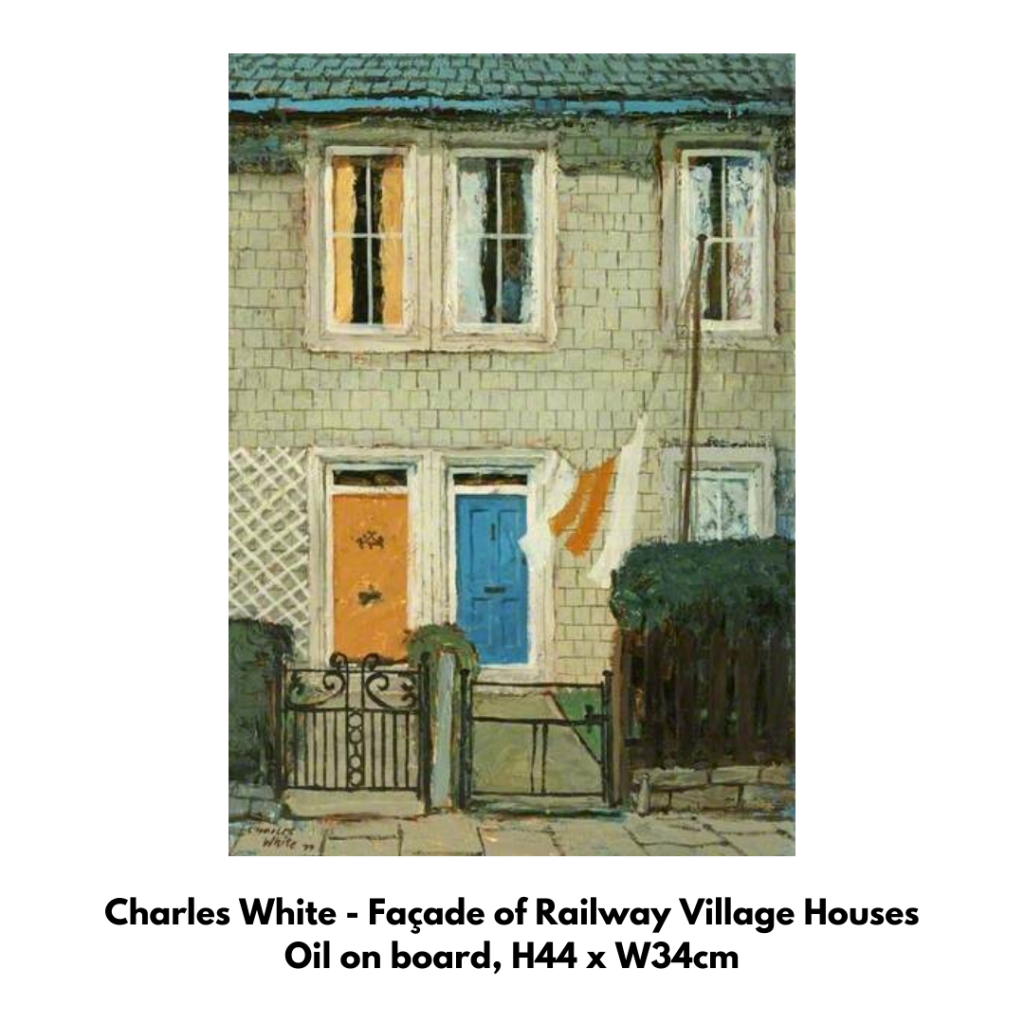

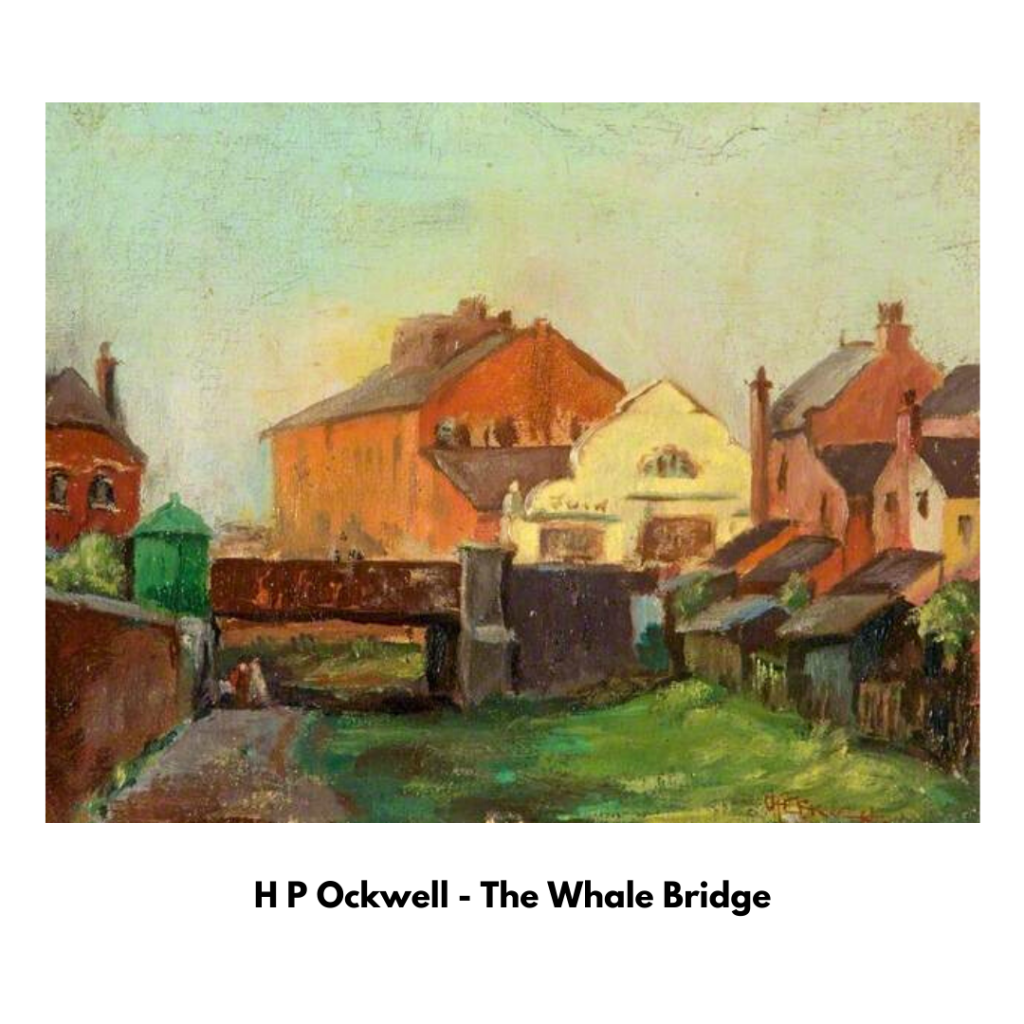

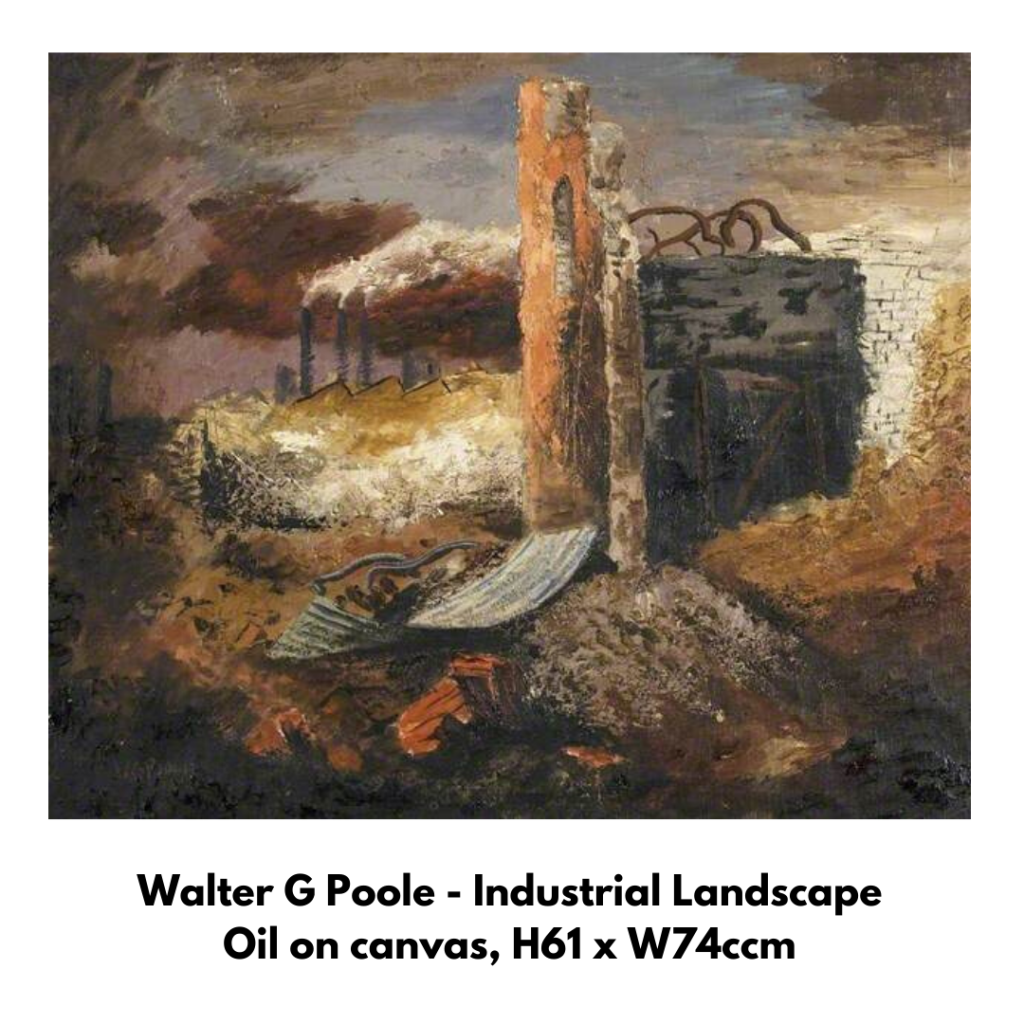

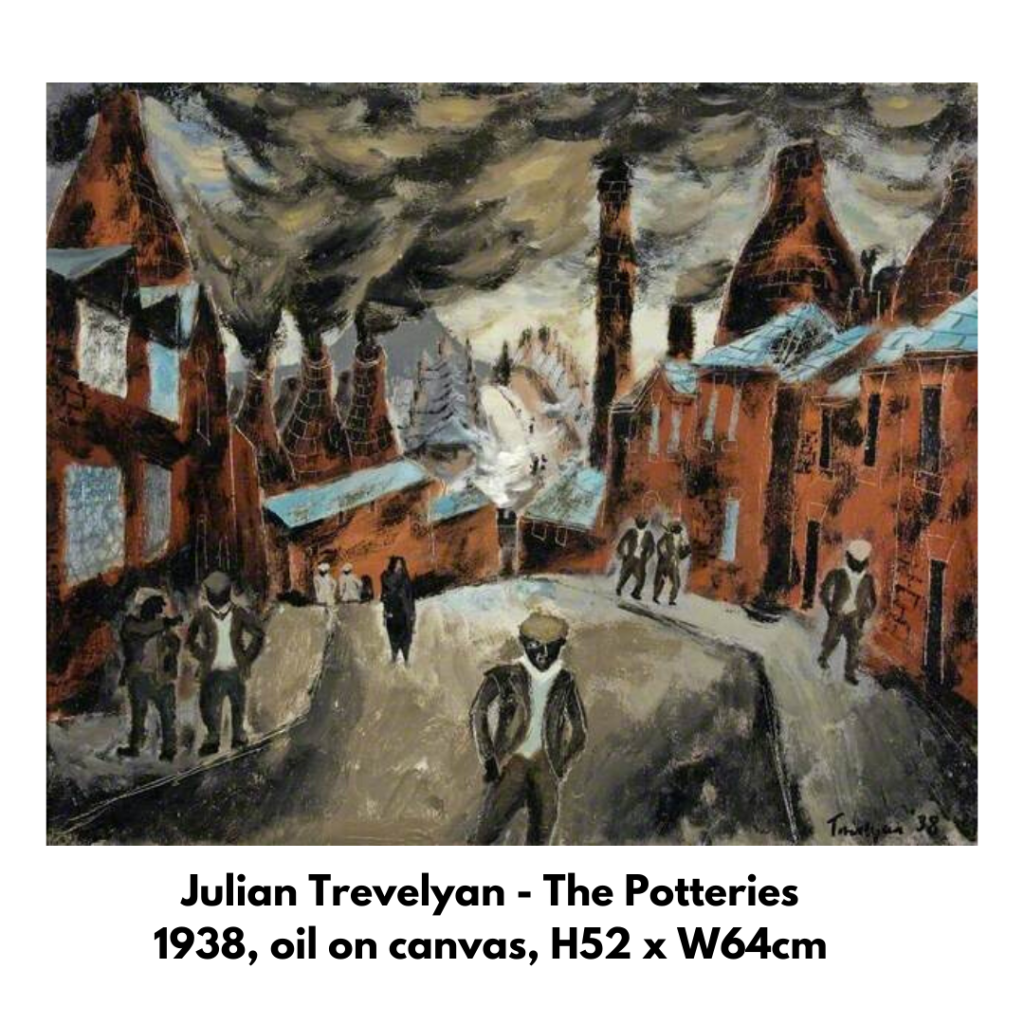

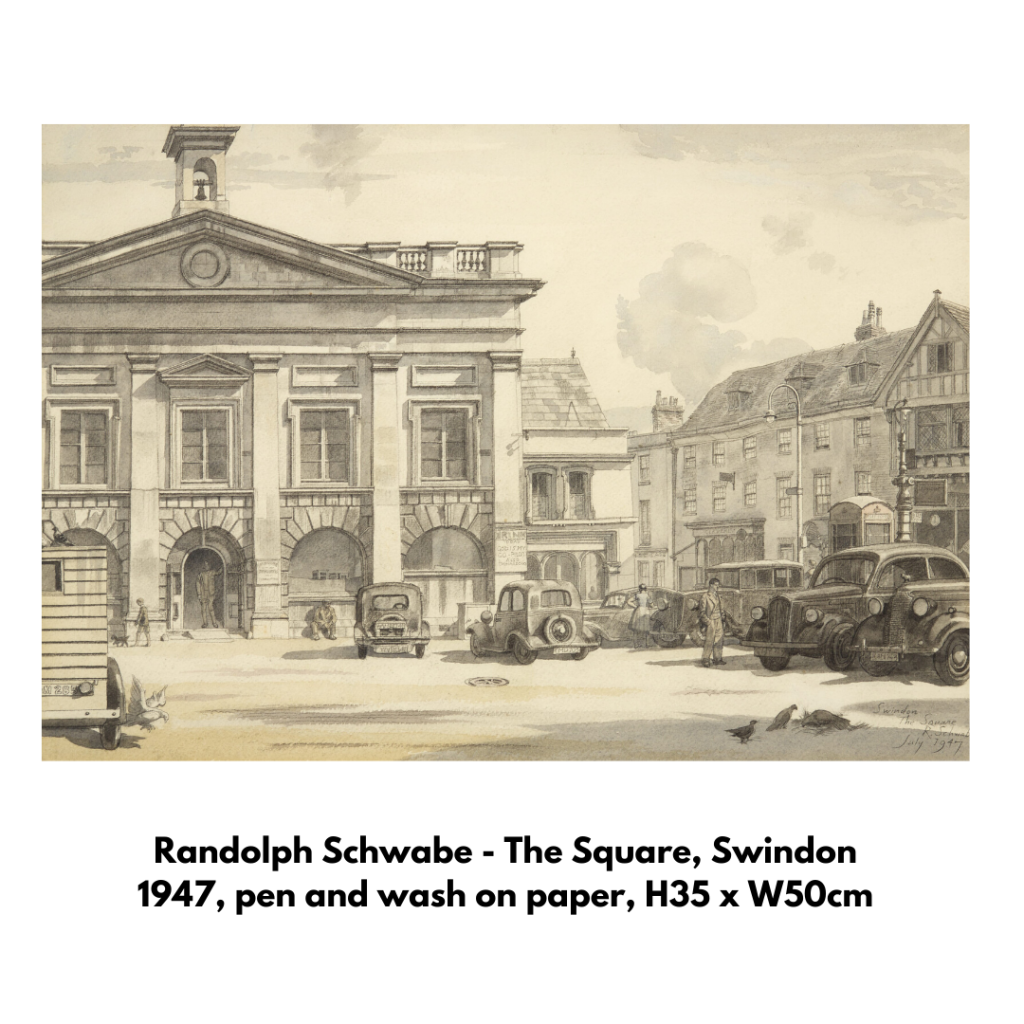

In early Renaissance art, buildings and architectural features were used as backdrops to religious and historical stories. Townscapes came into their own during the 17th Century Dutch Golden Age, which championed images of everyday life. By the late 19th Century, with increased industrialisation and the growth of urban spaces, townscapes had become highly regarded subject matter in their own right.

Through local townscapes we can explore the streets of Swindon as they used to be, and appreciate them as important records of our ever changing town. Modern and contemporary artworks demonstrate the many ways that artists can interpret the built environments surrounding them. Sometimes they encourage us to look closer at their interesting shapes and colours, and at others, they examine social and psychological questions which are bound up with specific urban surroundings.

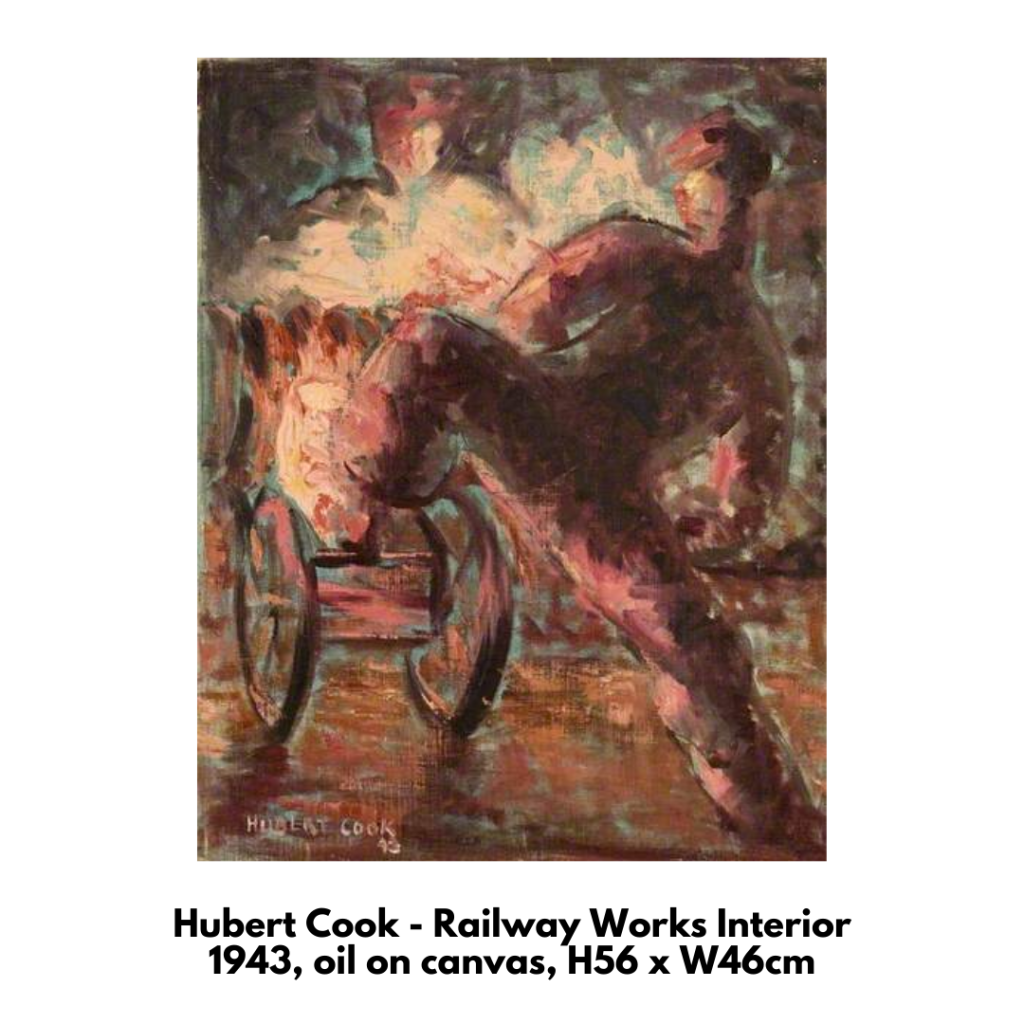

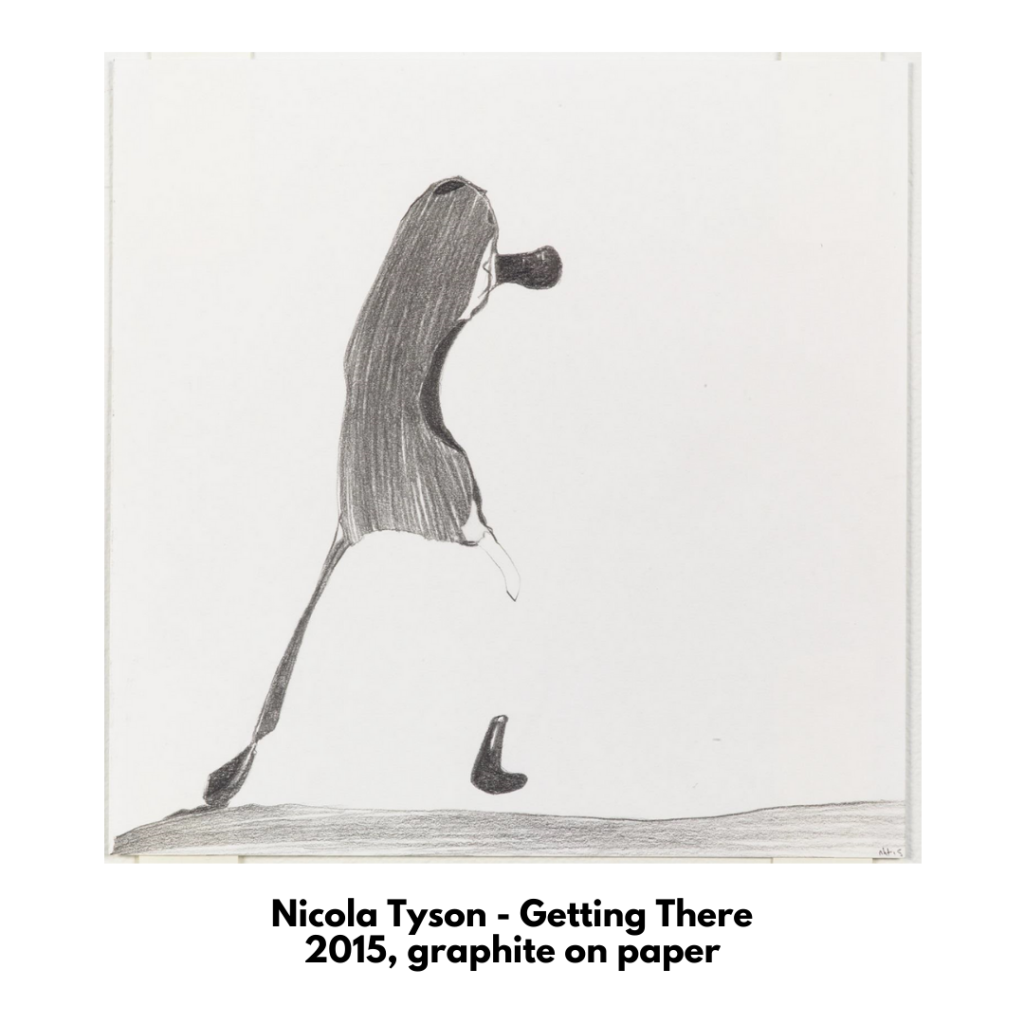

MOVEMENT:

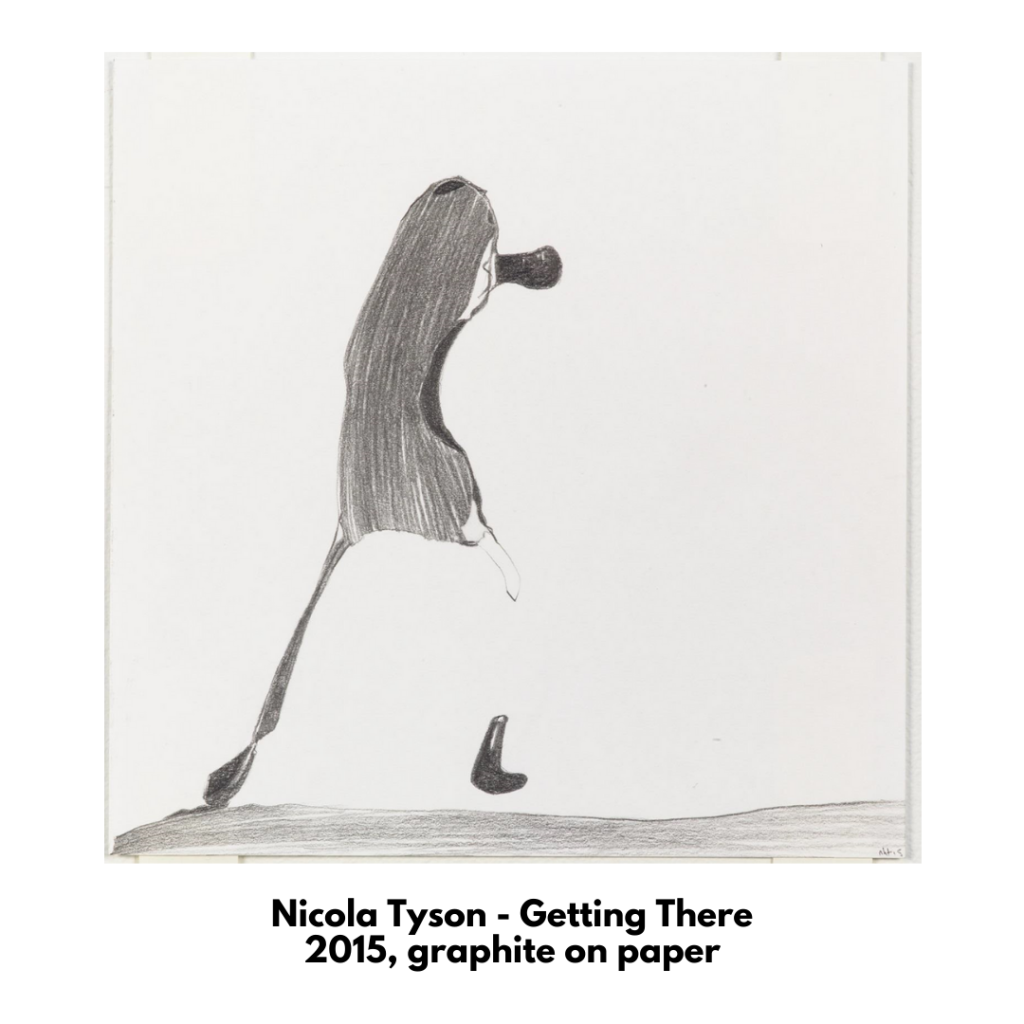

Different elements of an artwork can be used to create a sense of movement. Artists use line, colour, balance, rhythm, depth, space, and many other elements to create movement and direct the viewer’s eye. In the early 20th Century, Vorticist artists such as Edward Wadsworth, whose work features in the Swindon Collection, aimed to capture the dynamism of the emerging modern world. The Vorticists were inspired by changing new technologies and the increasing speed of life. Swindon Collection artist David Bomberg described this idea that ‘the new life should find its expression in a new art, which has been stimulated by new perceptions. I want to translate the life of a great city, its motion, its machinery, into an art that shall not be photographic, but expressive.’

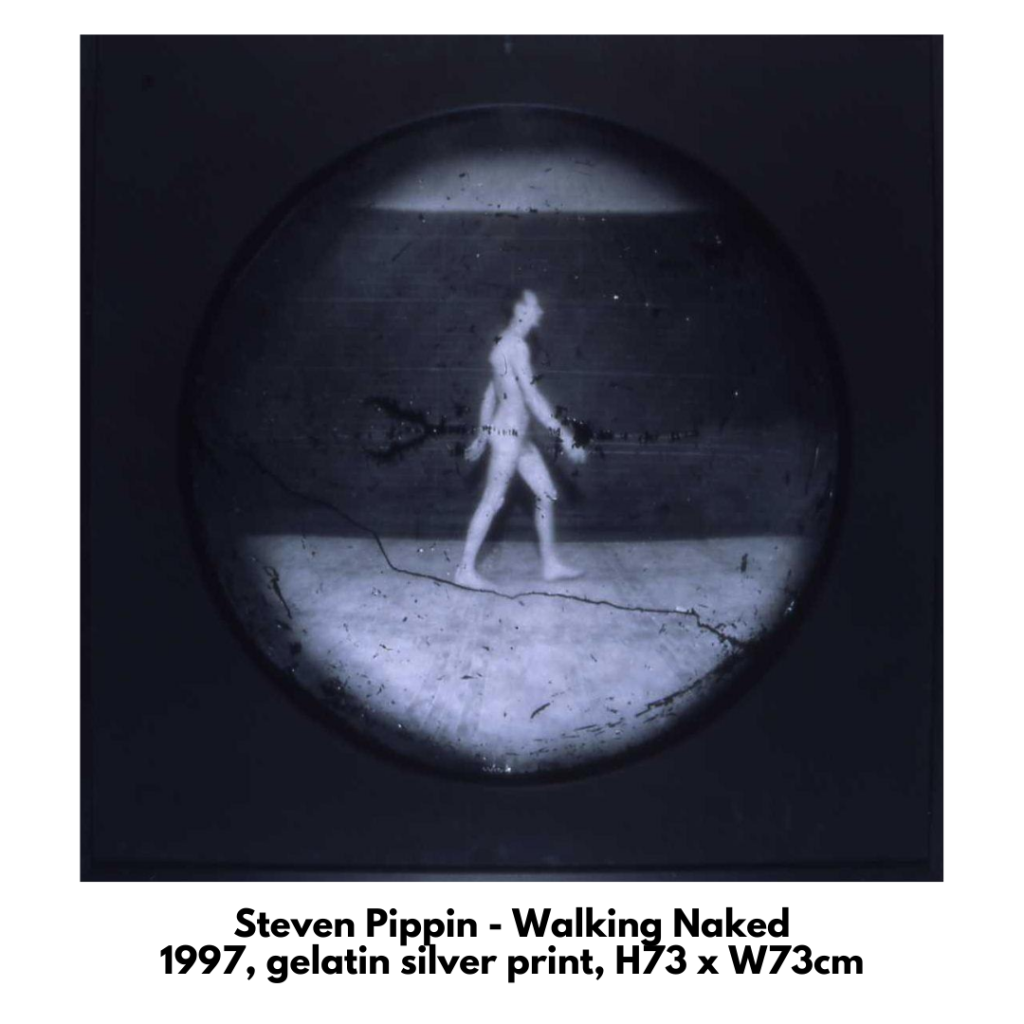

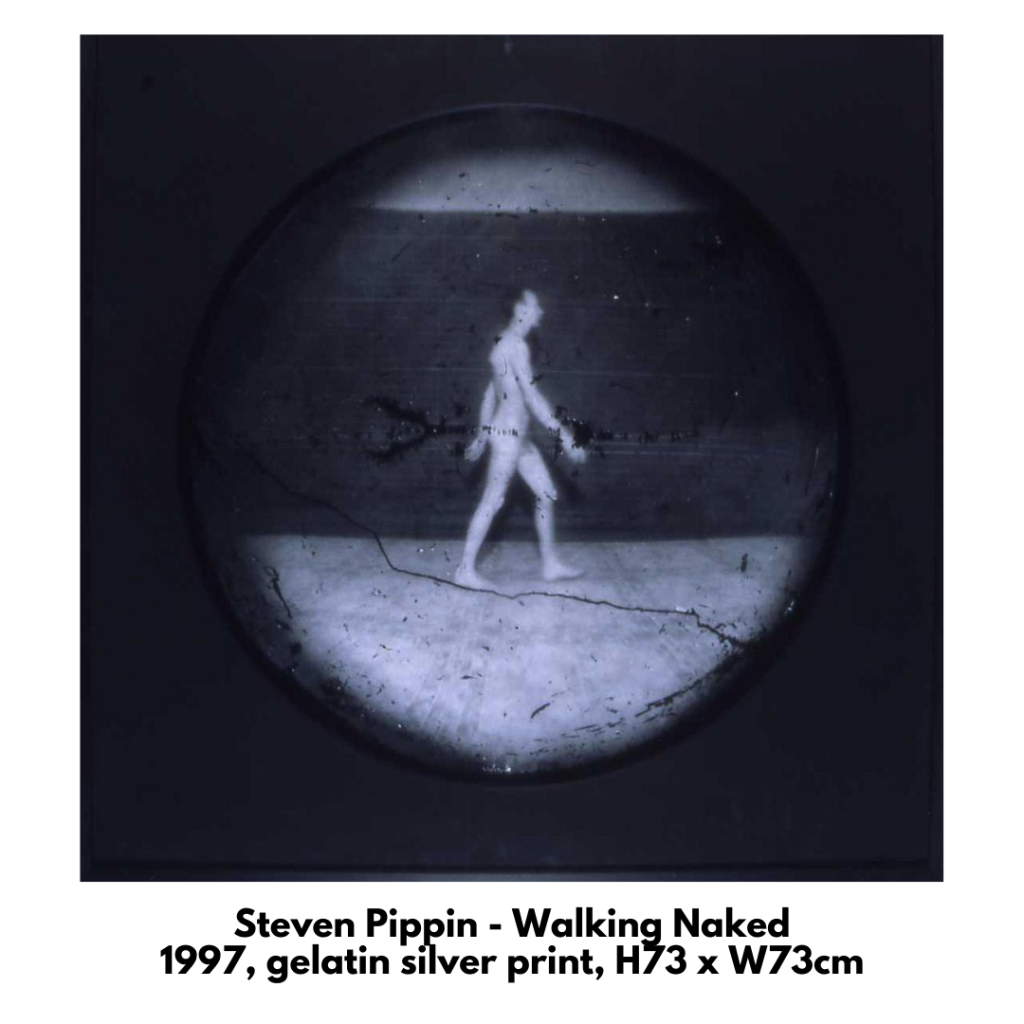

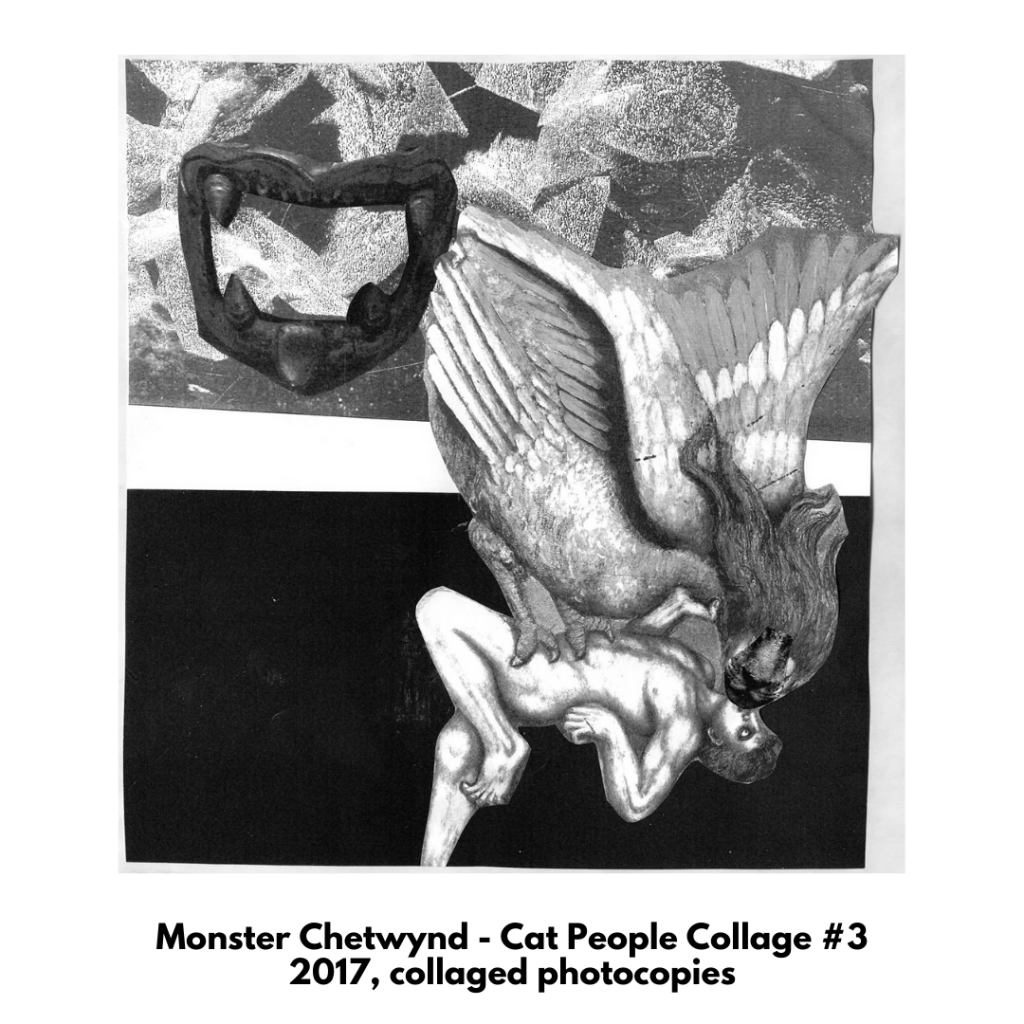

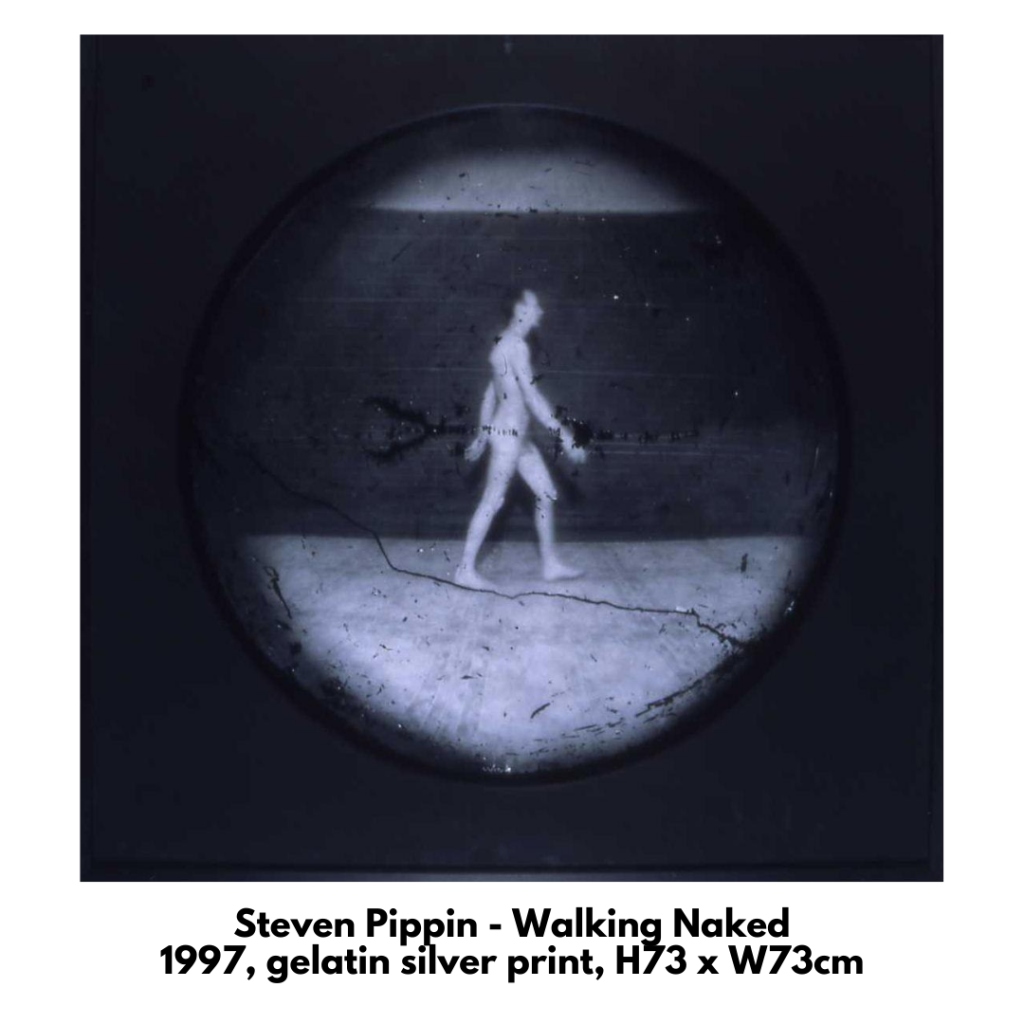

Some contemporary artists have turned to photography and film to capture movement. The Swindon Collection features a series of pinhole camera photographs by Turner Prize-winning Steven Pippin which capture him walking naked through a launderette! Some contemporary artists have embraced movement even further in their works, producing kinetic art – art that actually moves – and using movement in their performance and installation art. Swindon Collection artist Monster Chetwynd was nominated for the Turner Prize for her movement-inspired performance art in 2012.

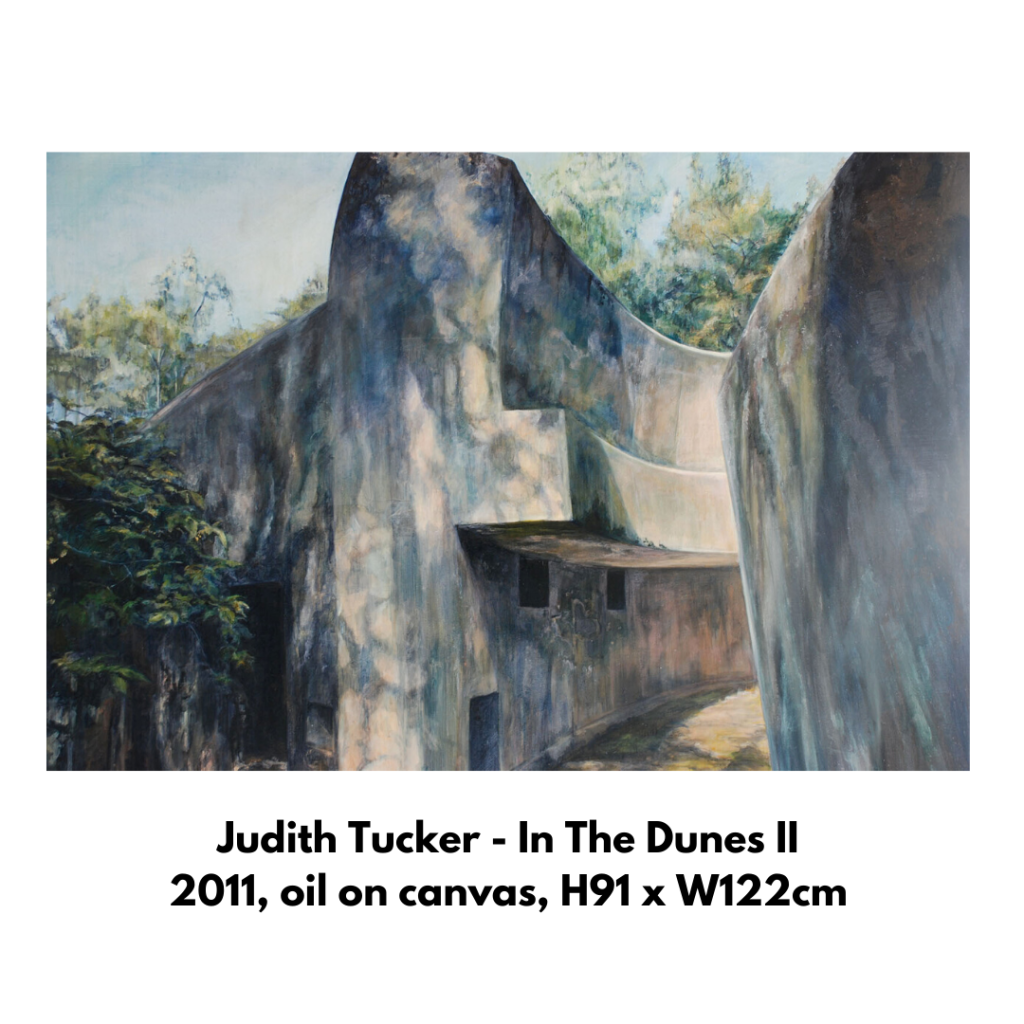

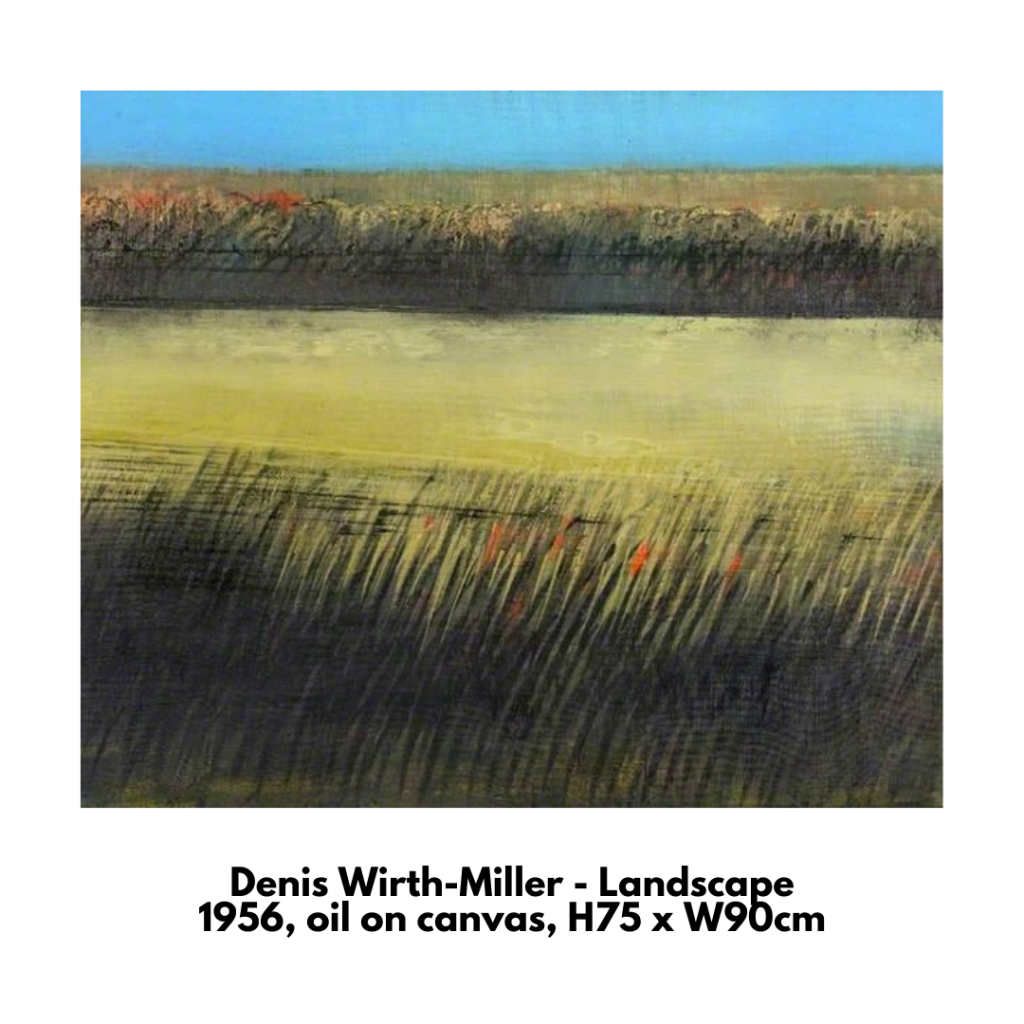

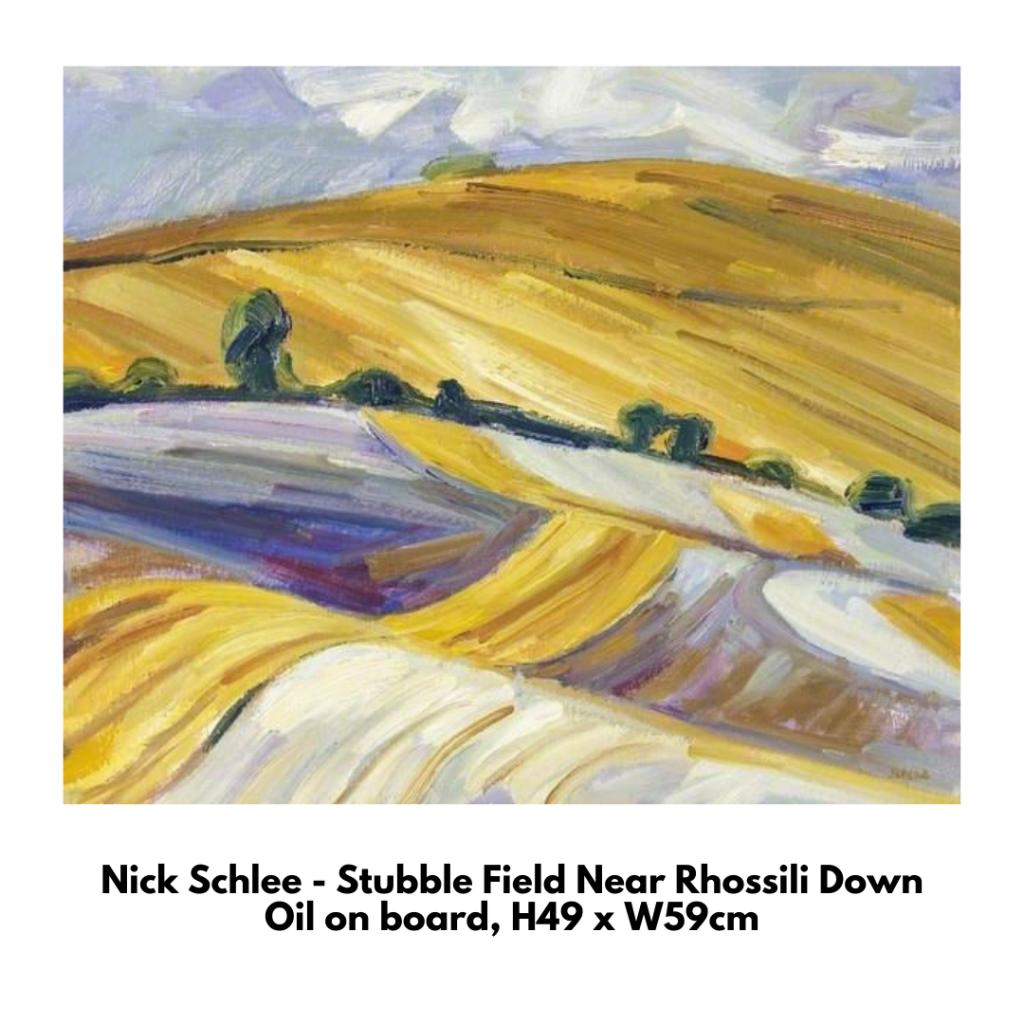

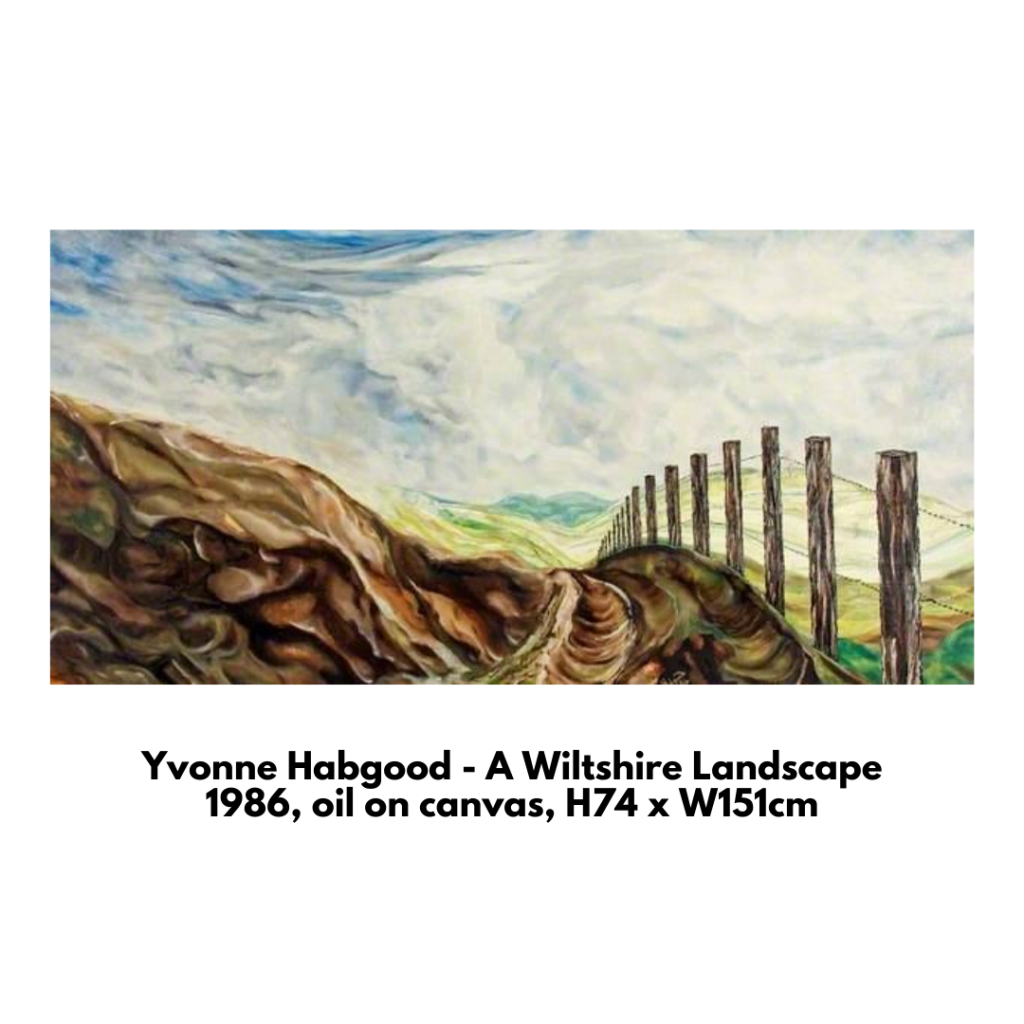

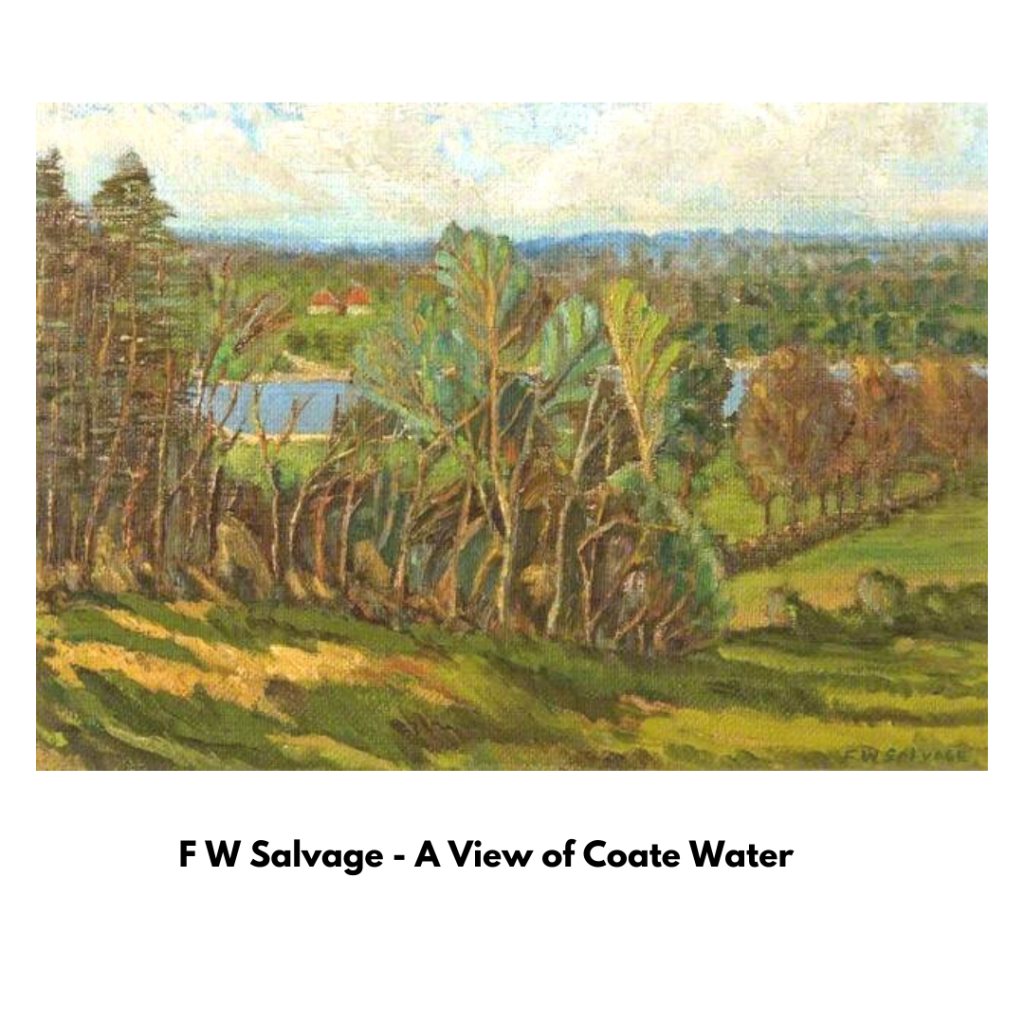

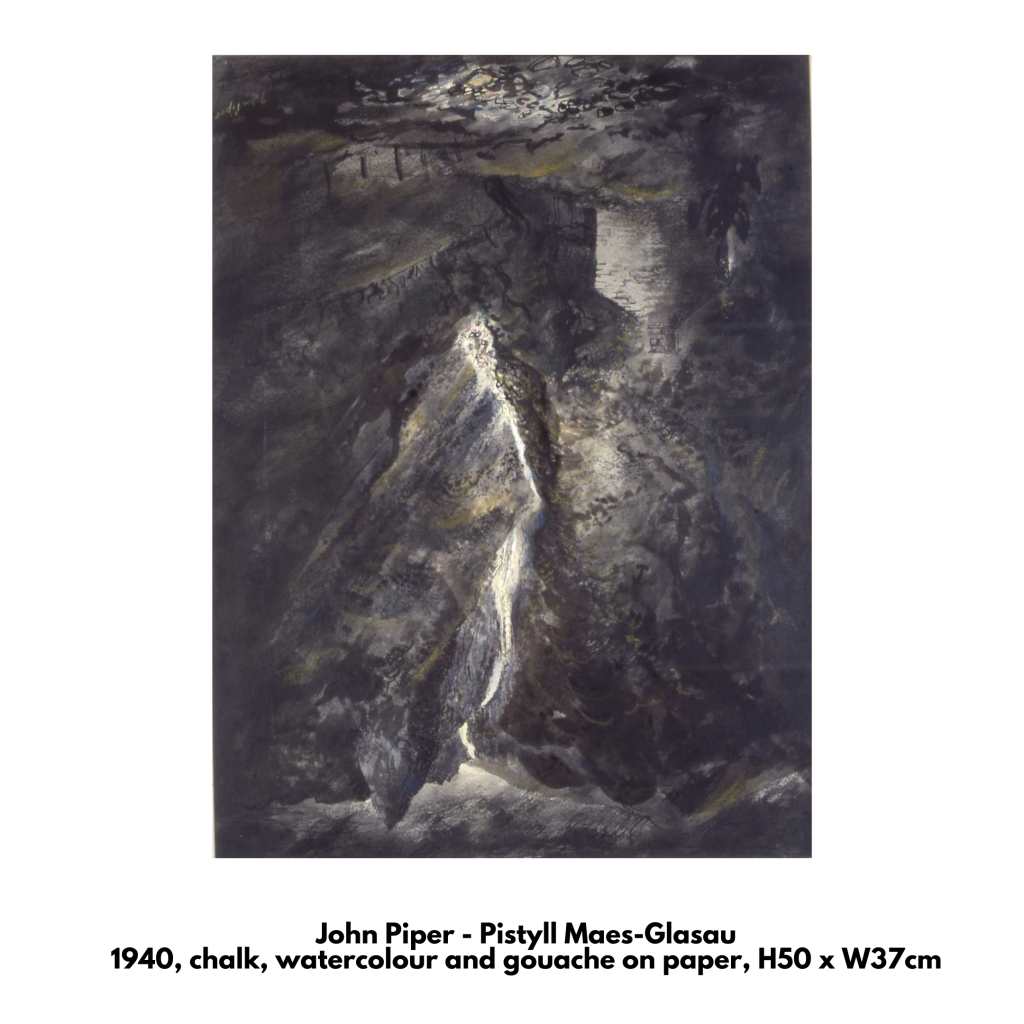

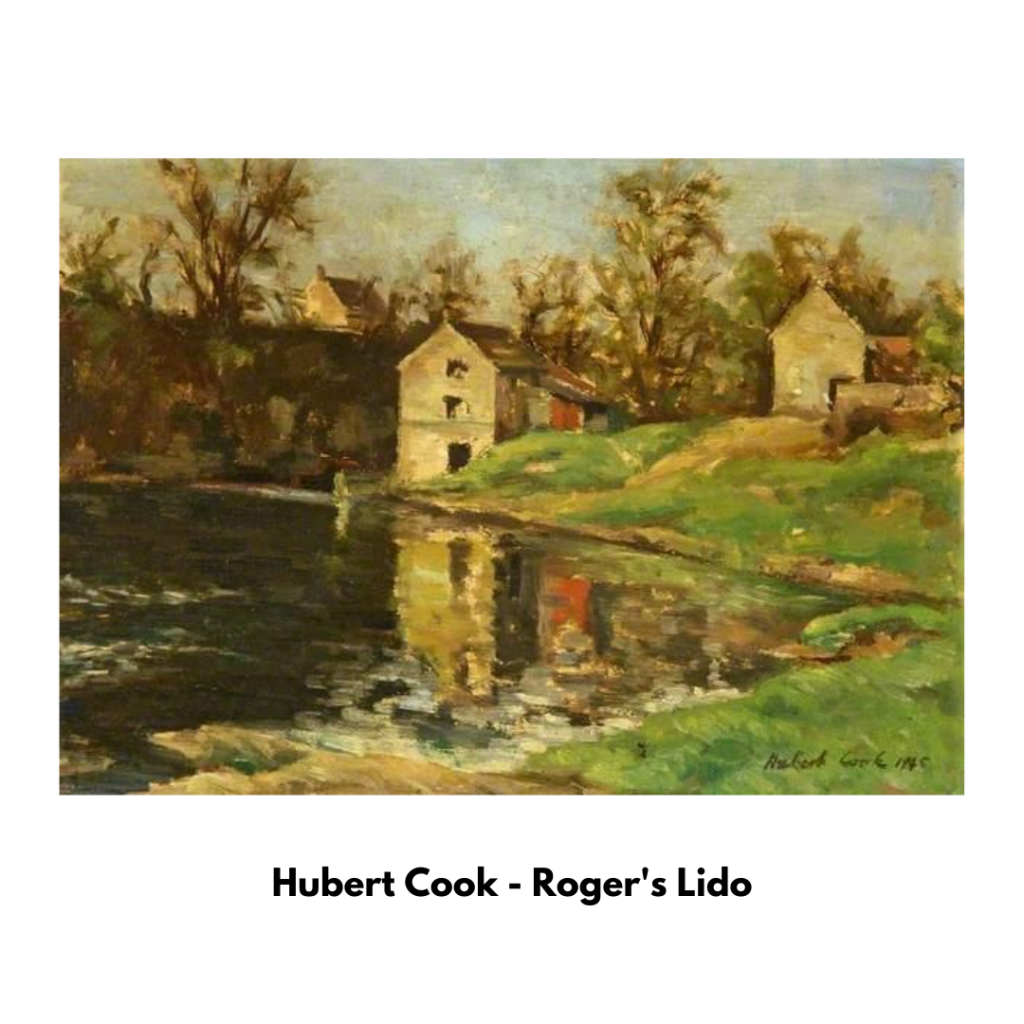

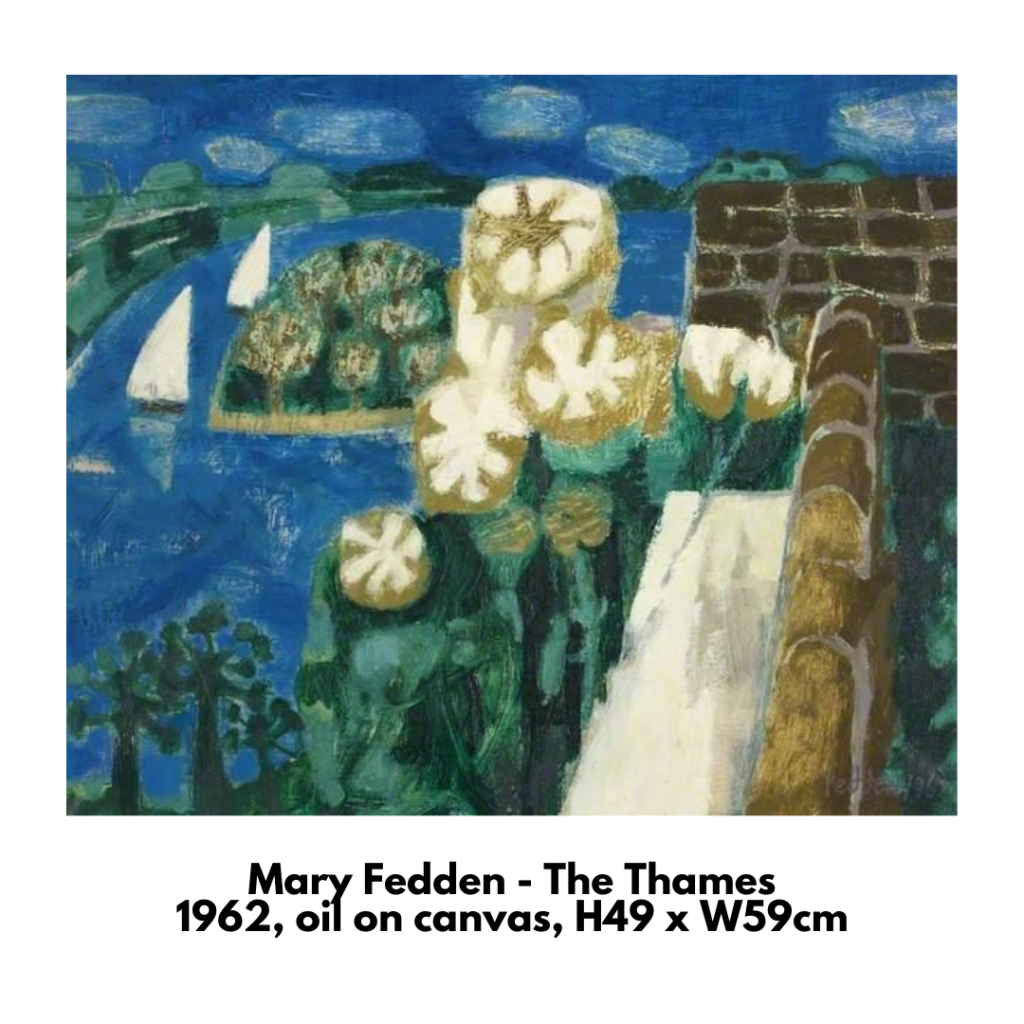

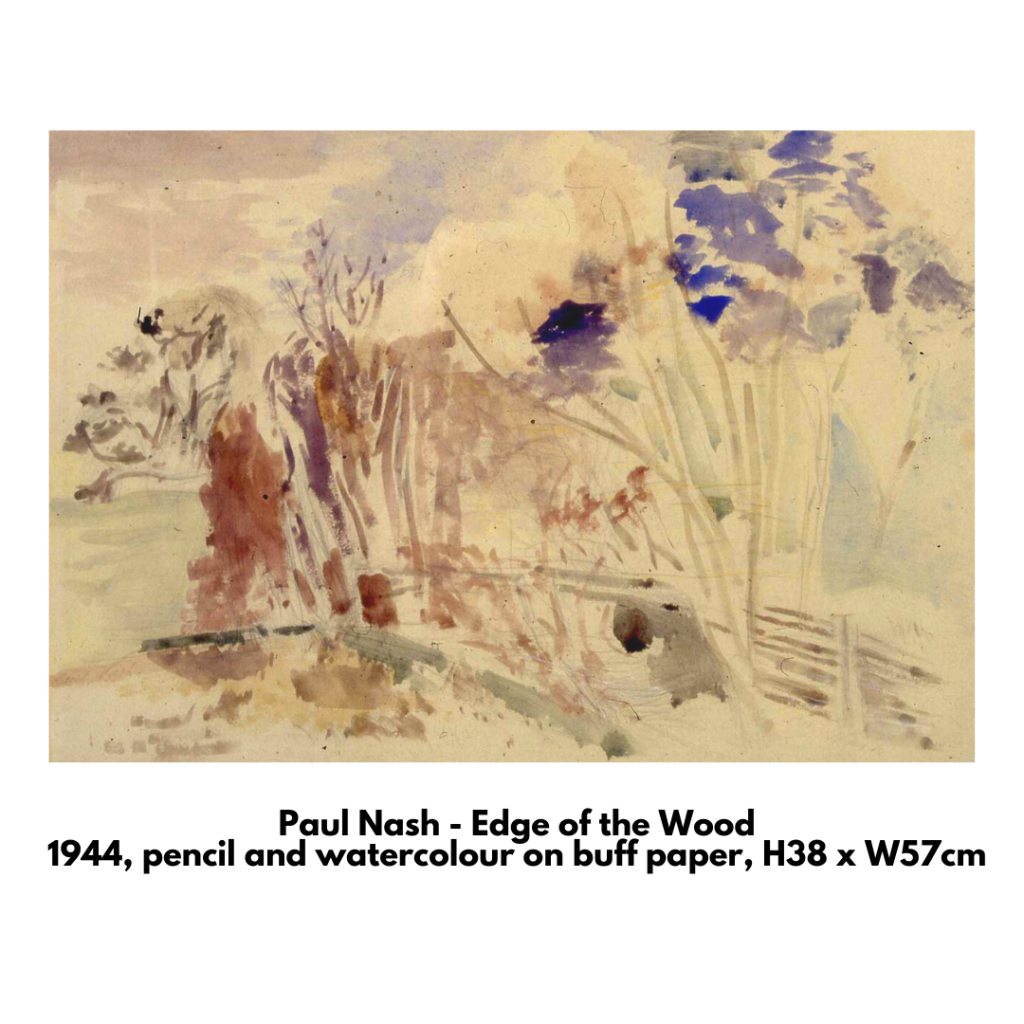

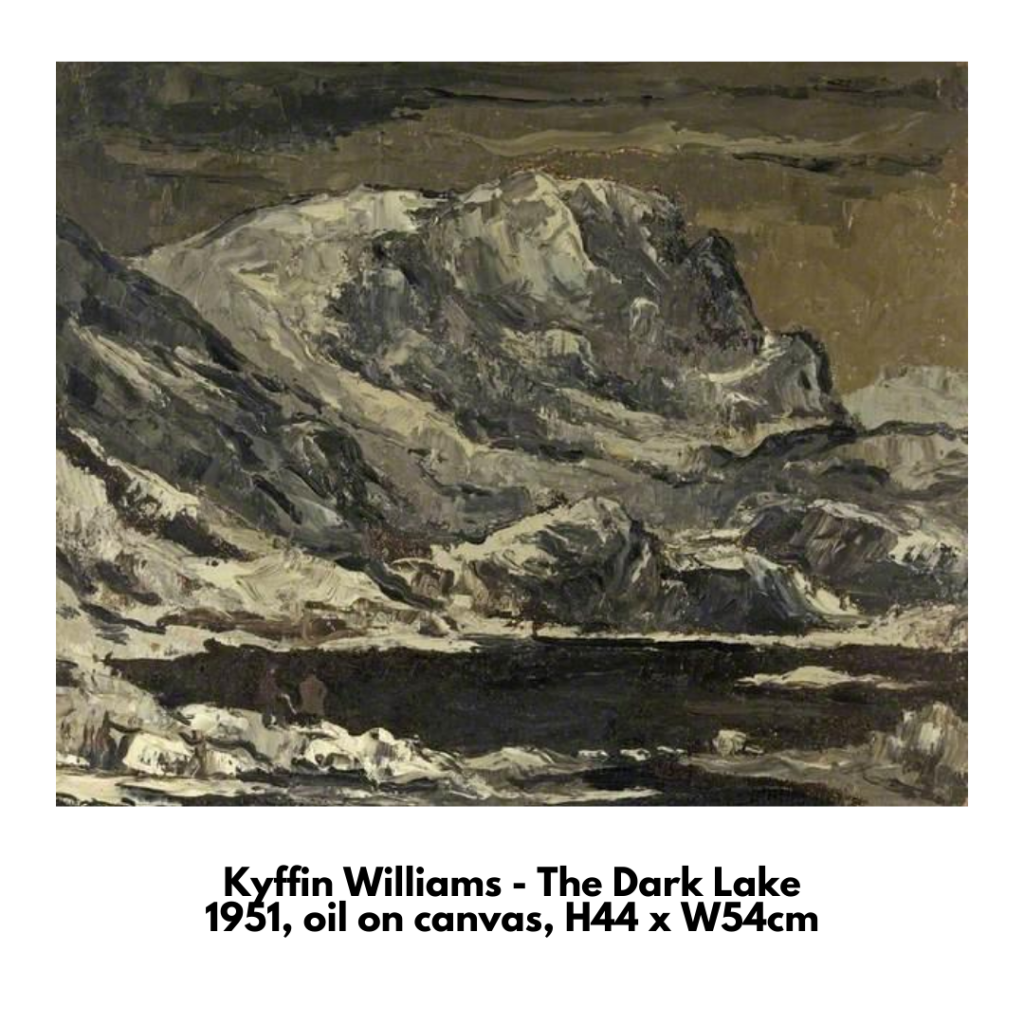

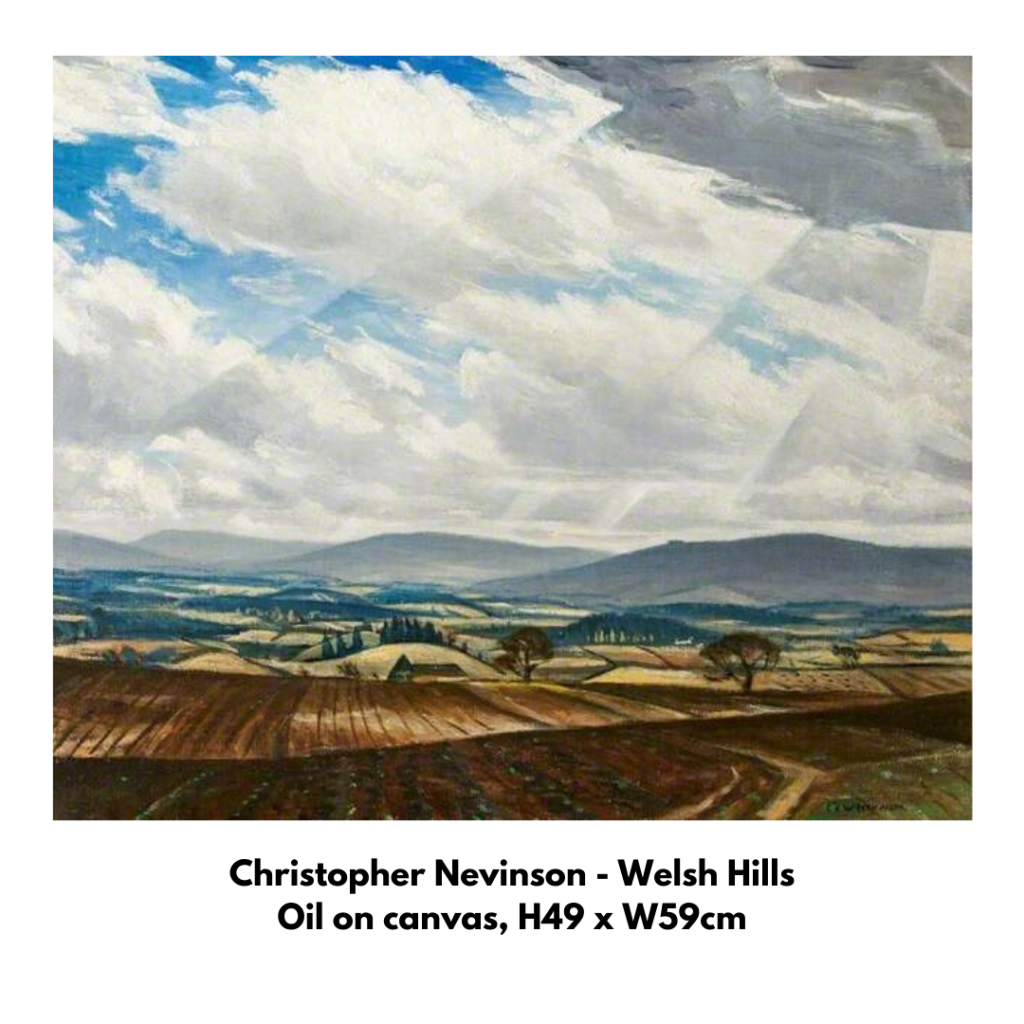

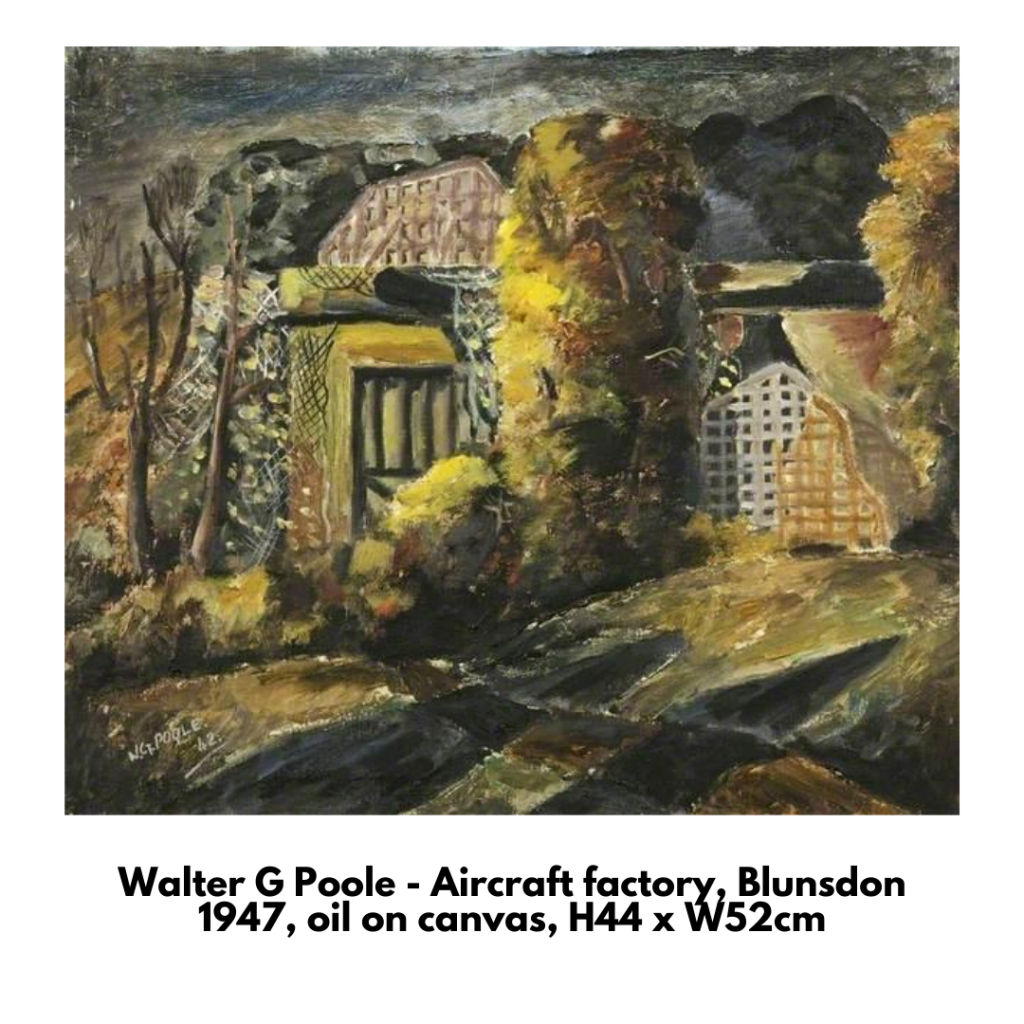

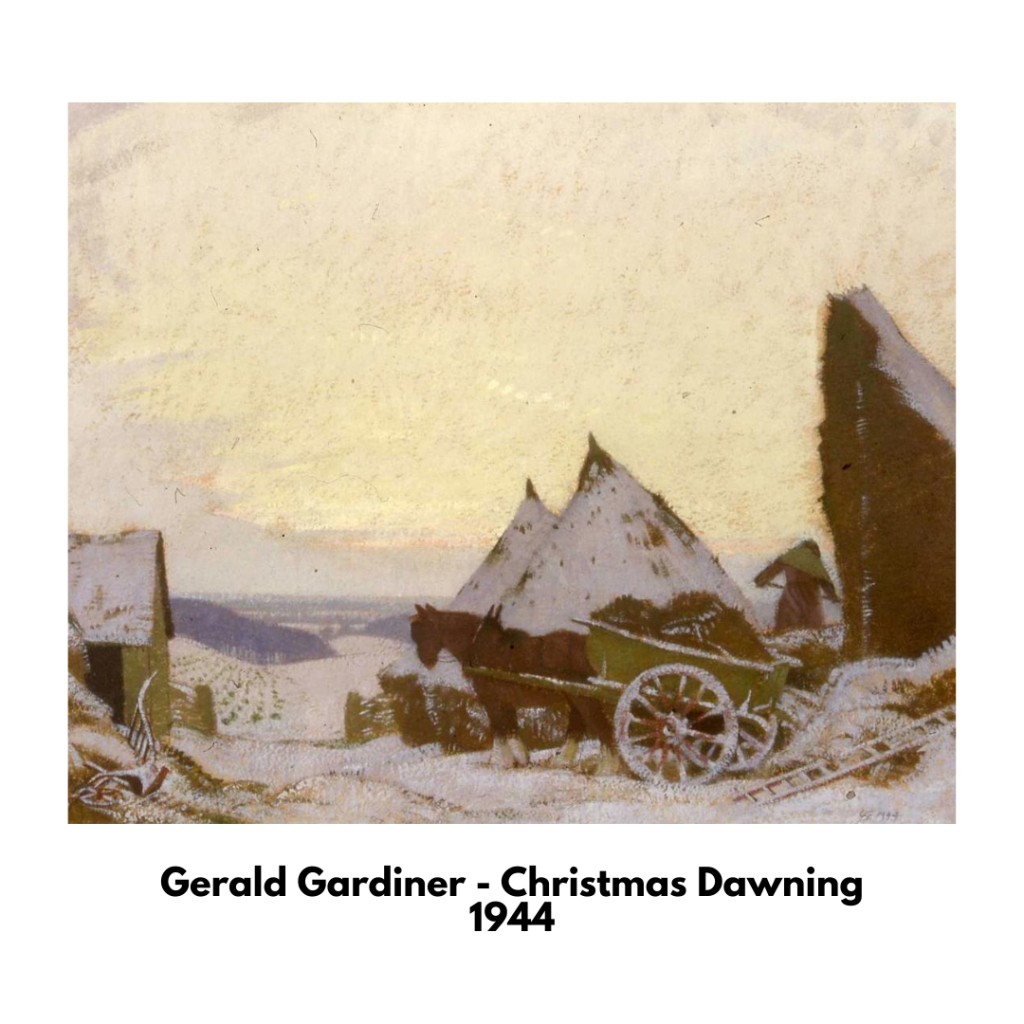

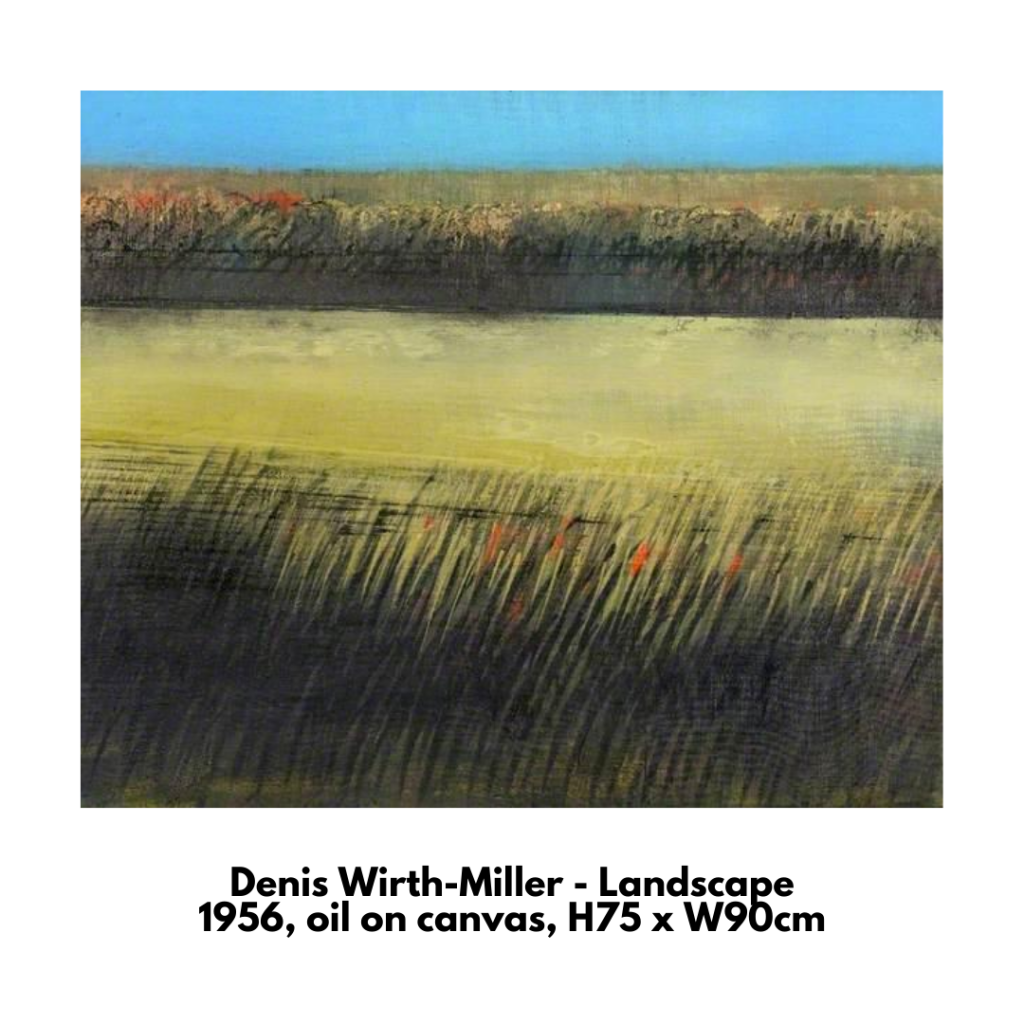

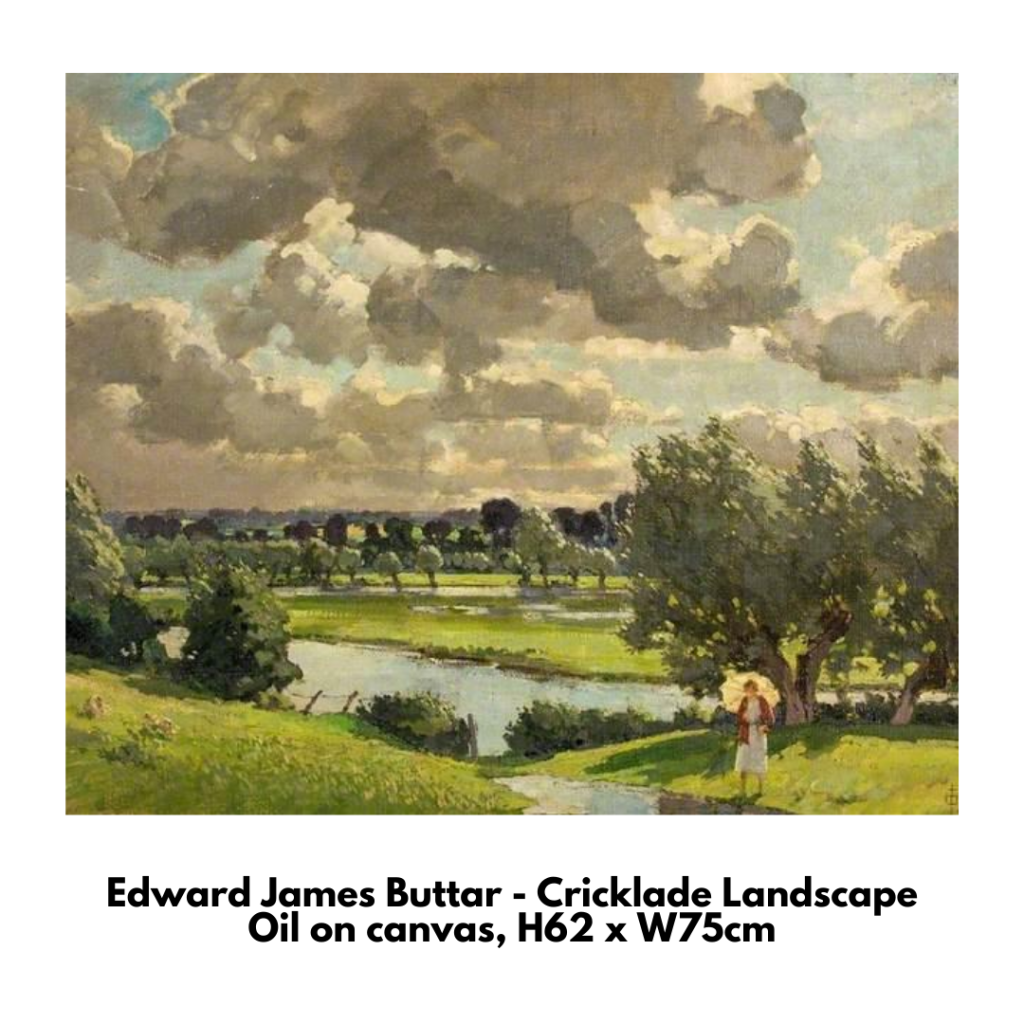

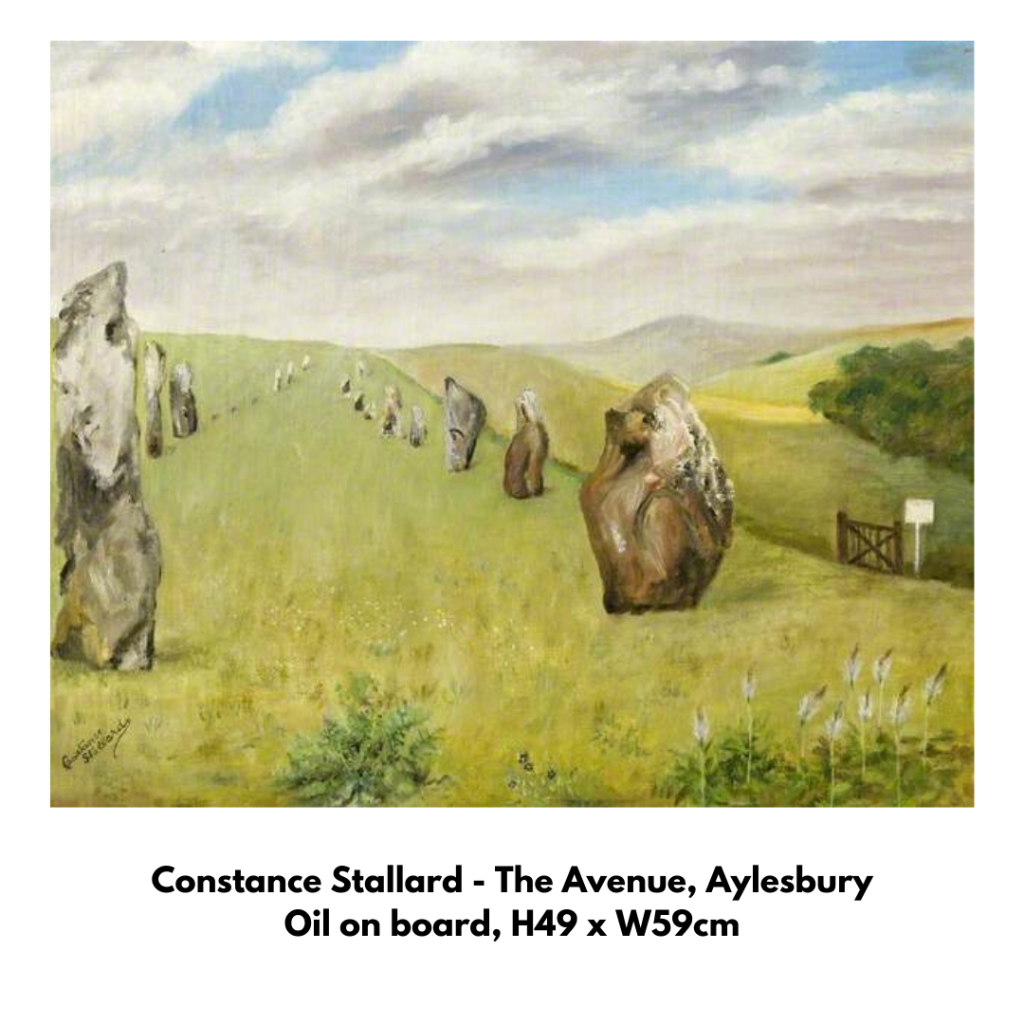

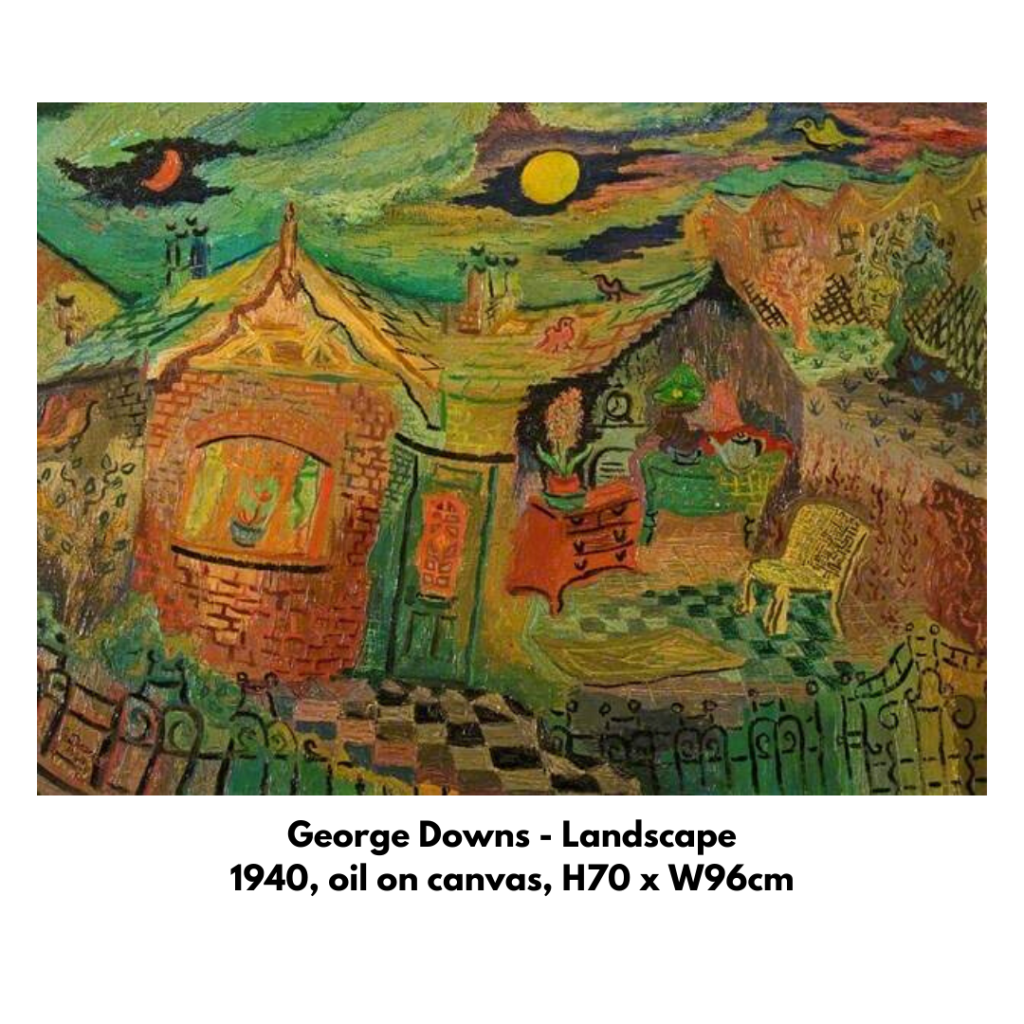

LANDSCAPE:

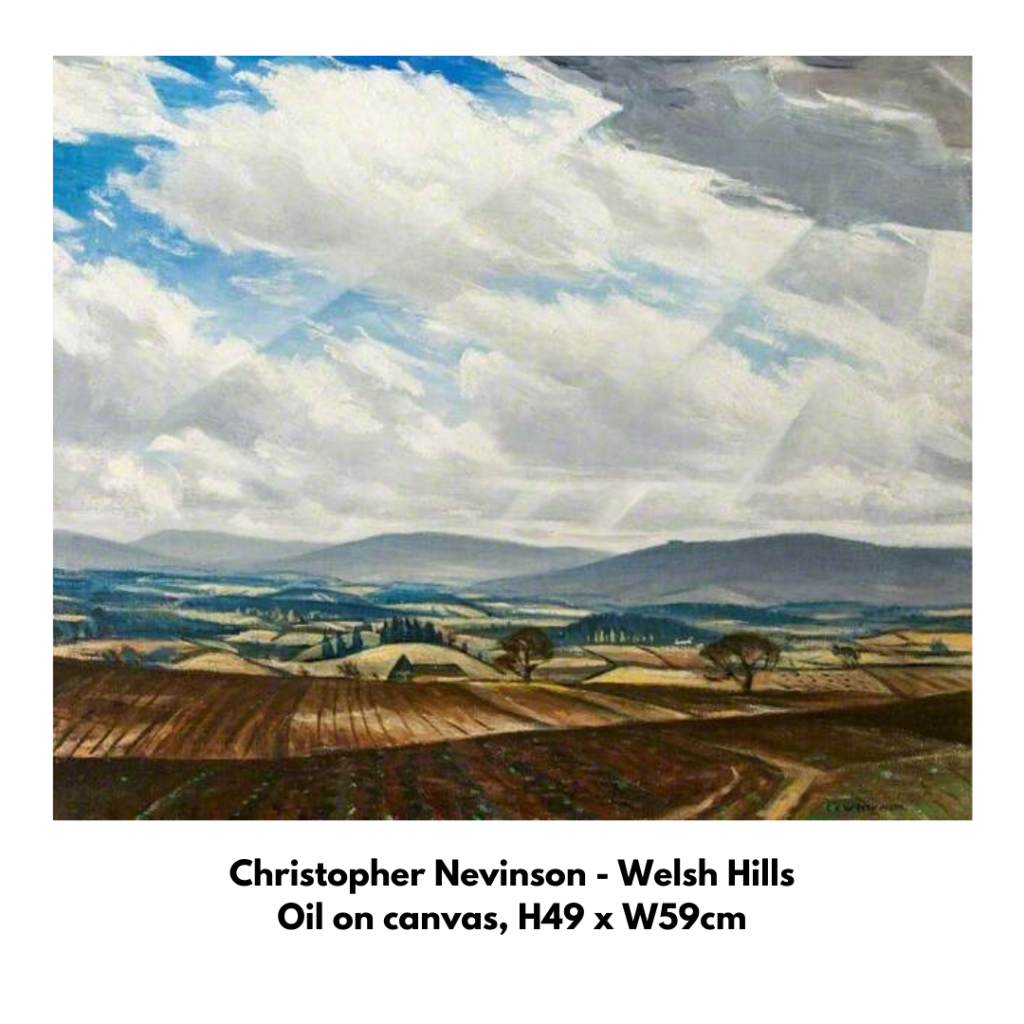

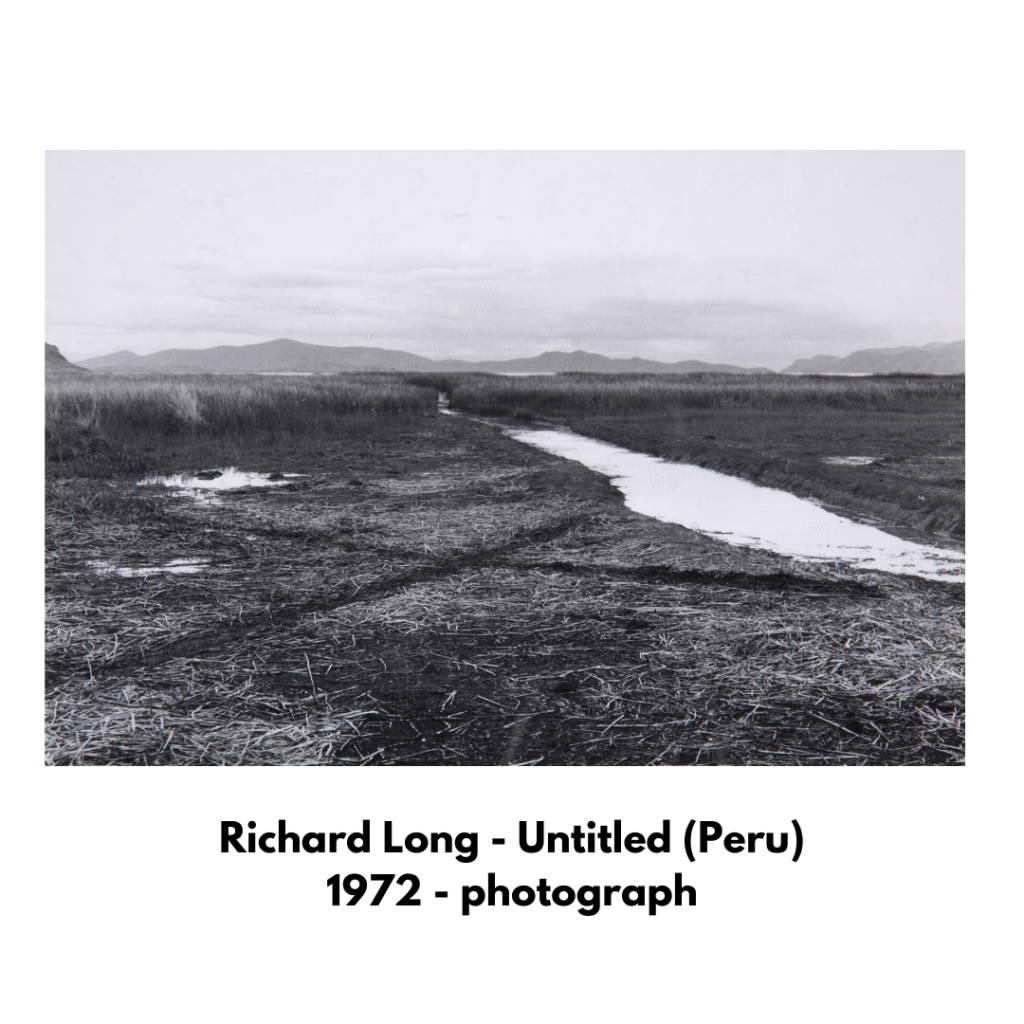

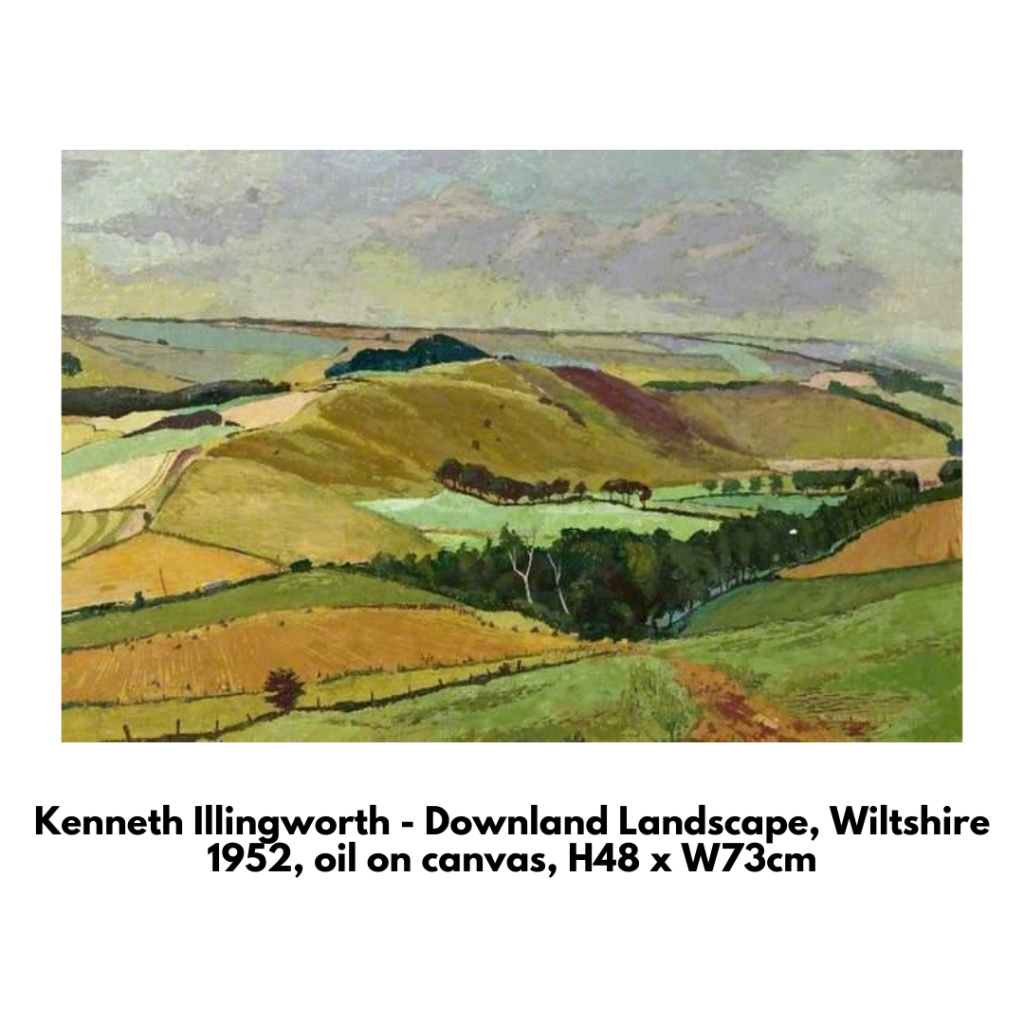

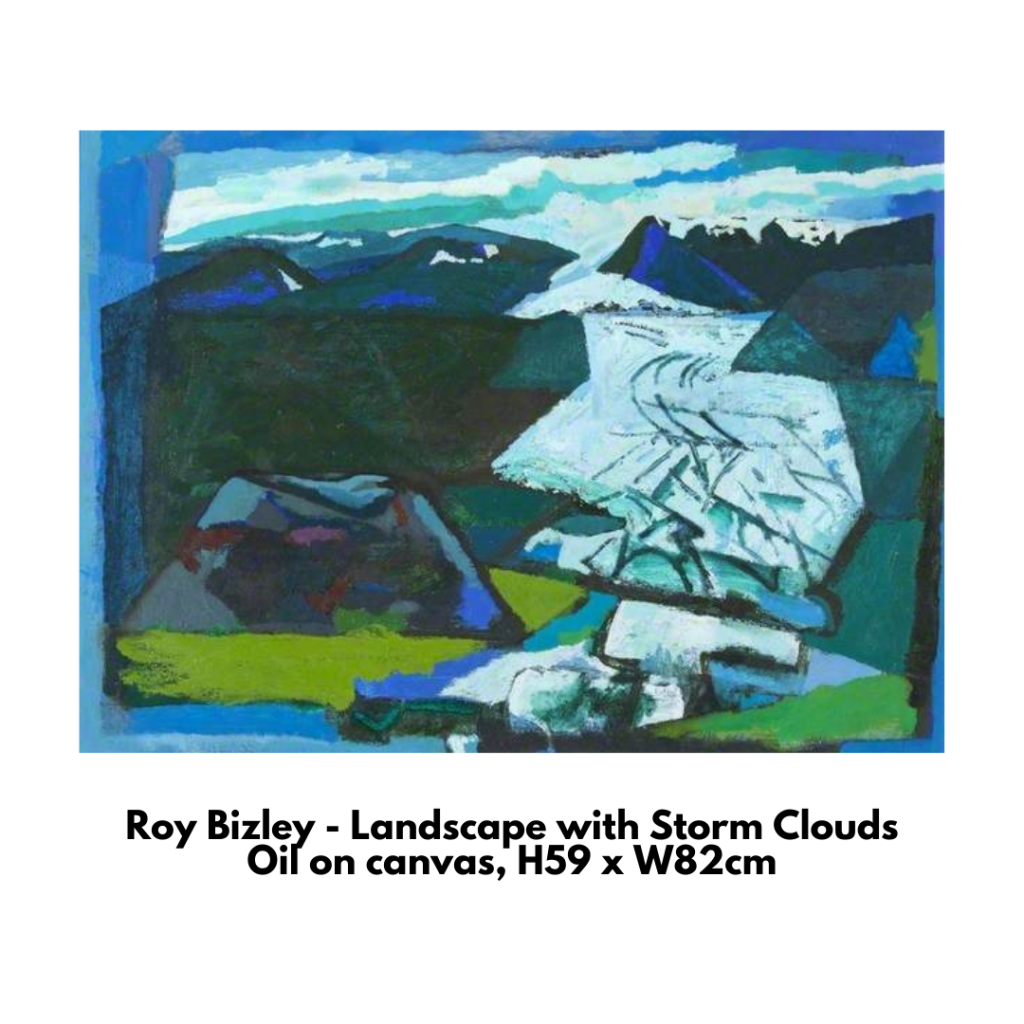

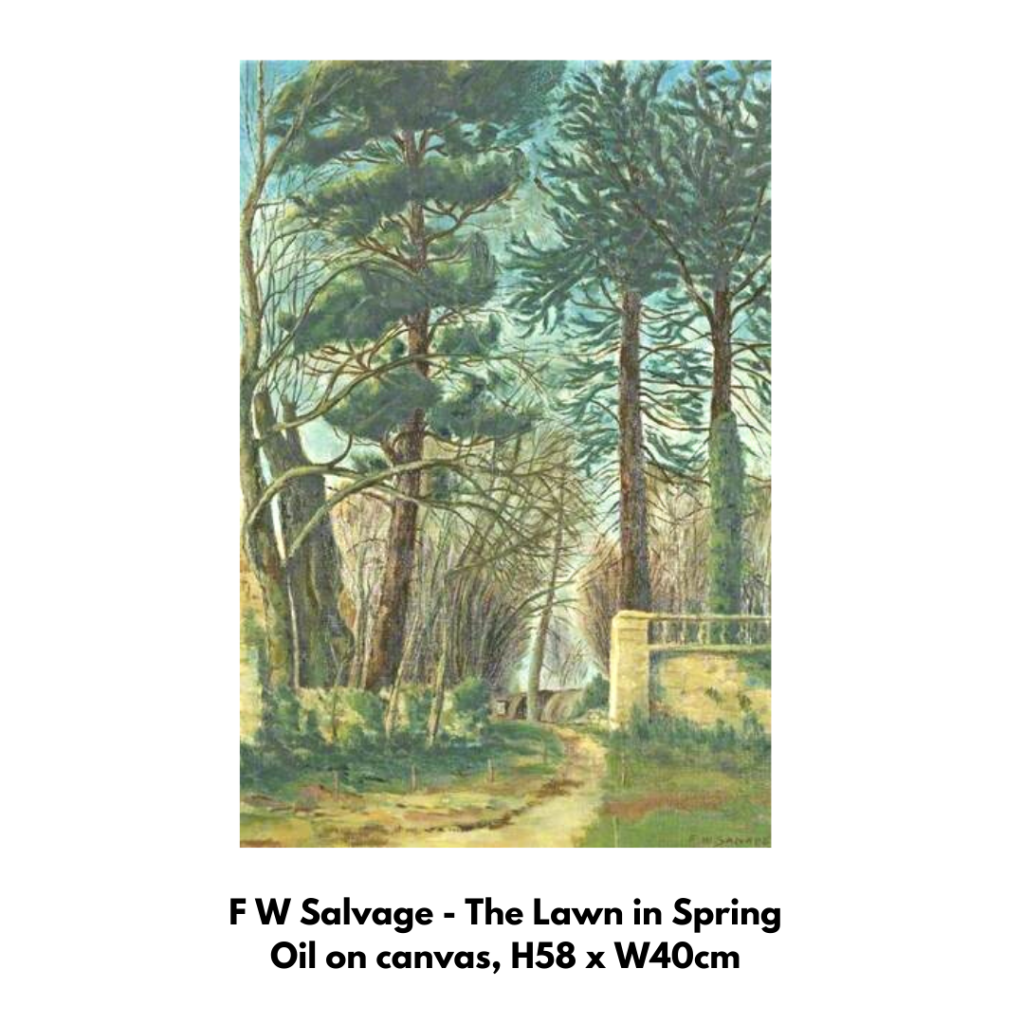

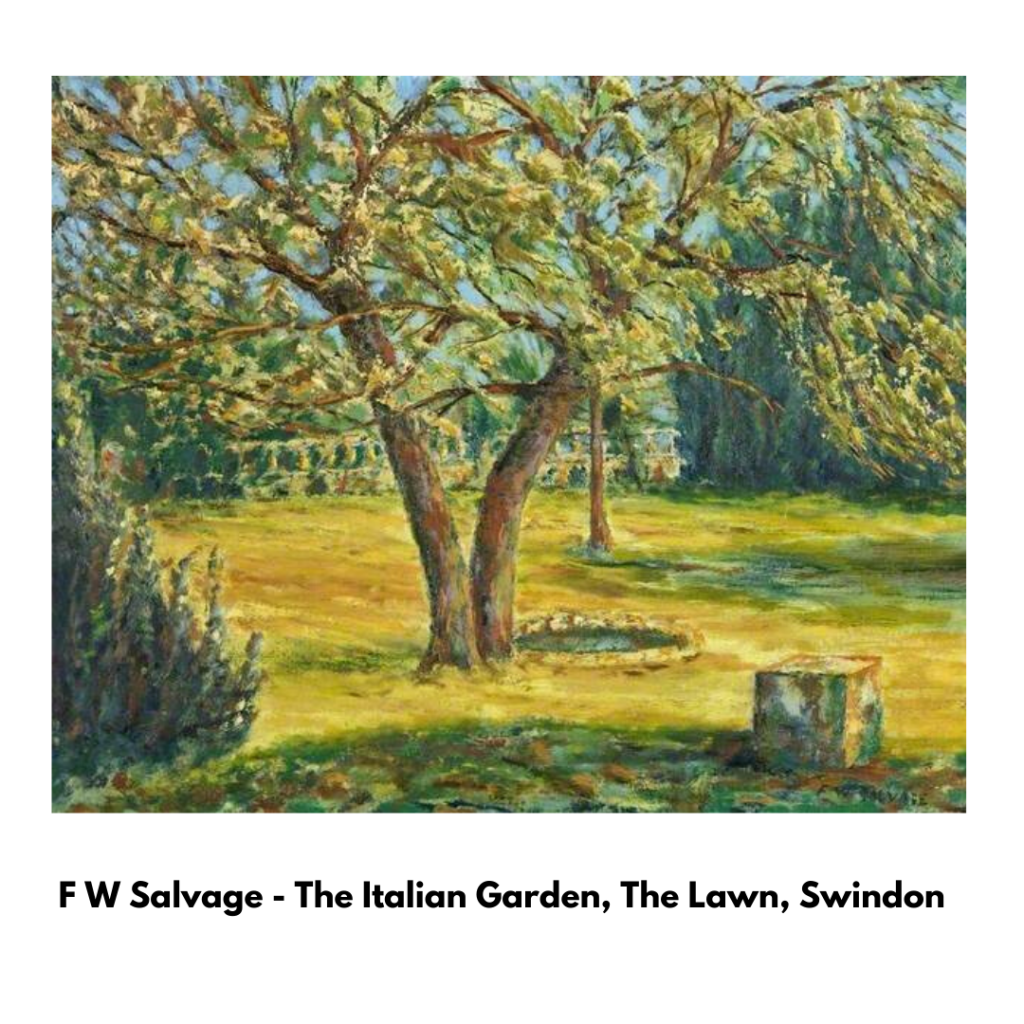

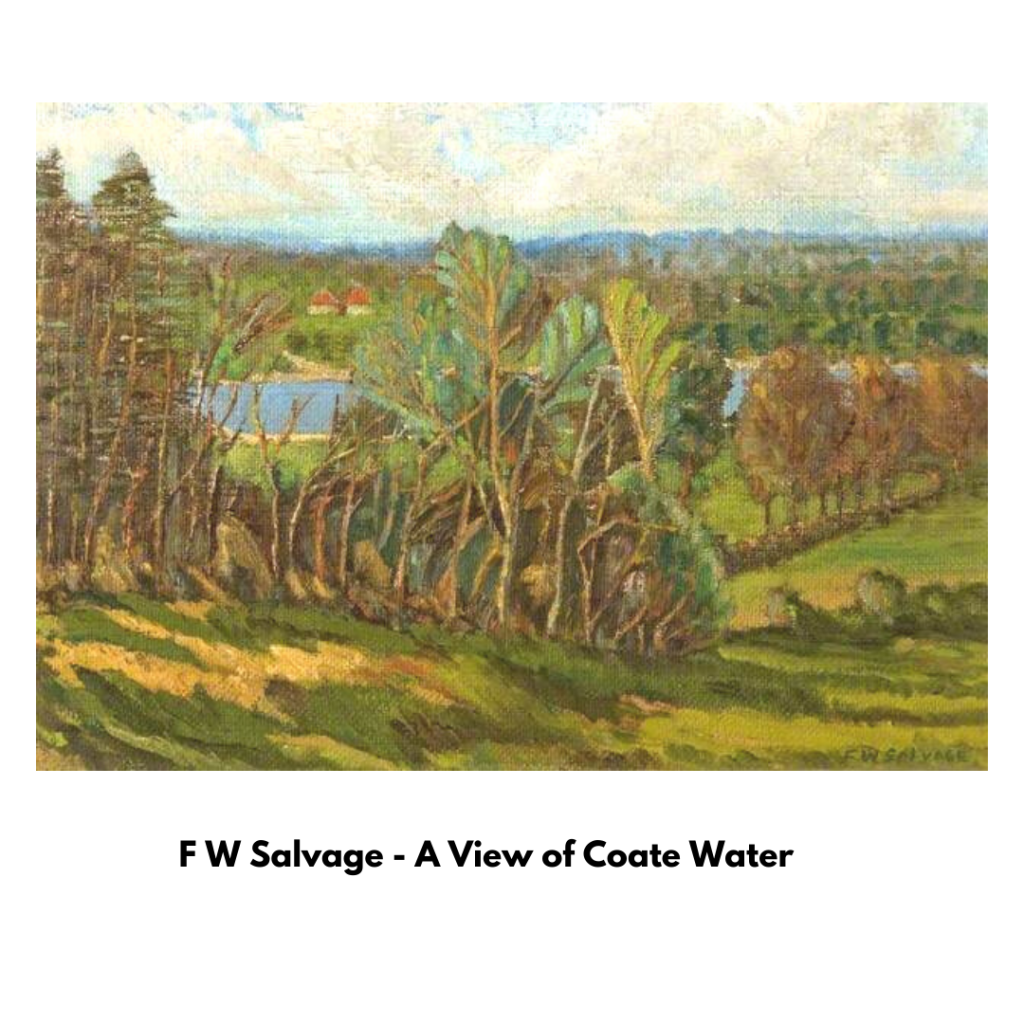

Before the 17th century, landscapes were confined to the backgrounds of portraits or to paintings with religious or historical subjects. During the 17th Century, landscape became an important subject in its own right, as paintings began to depict classical Greek or Roman landscapes. The explosion of naturalistic landscape painting in the 19th Century, from the likes of Turner and Constable, coincided with wide-spread industrialisation and urbanisation, which increasingly alienated people from nature. The Impressionists further cemented the role of landscape as a key genre within Western Art.

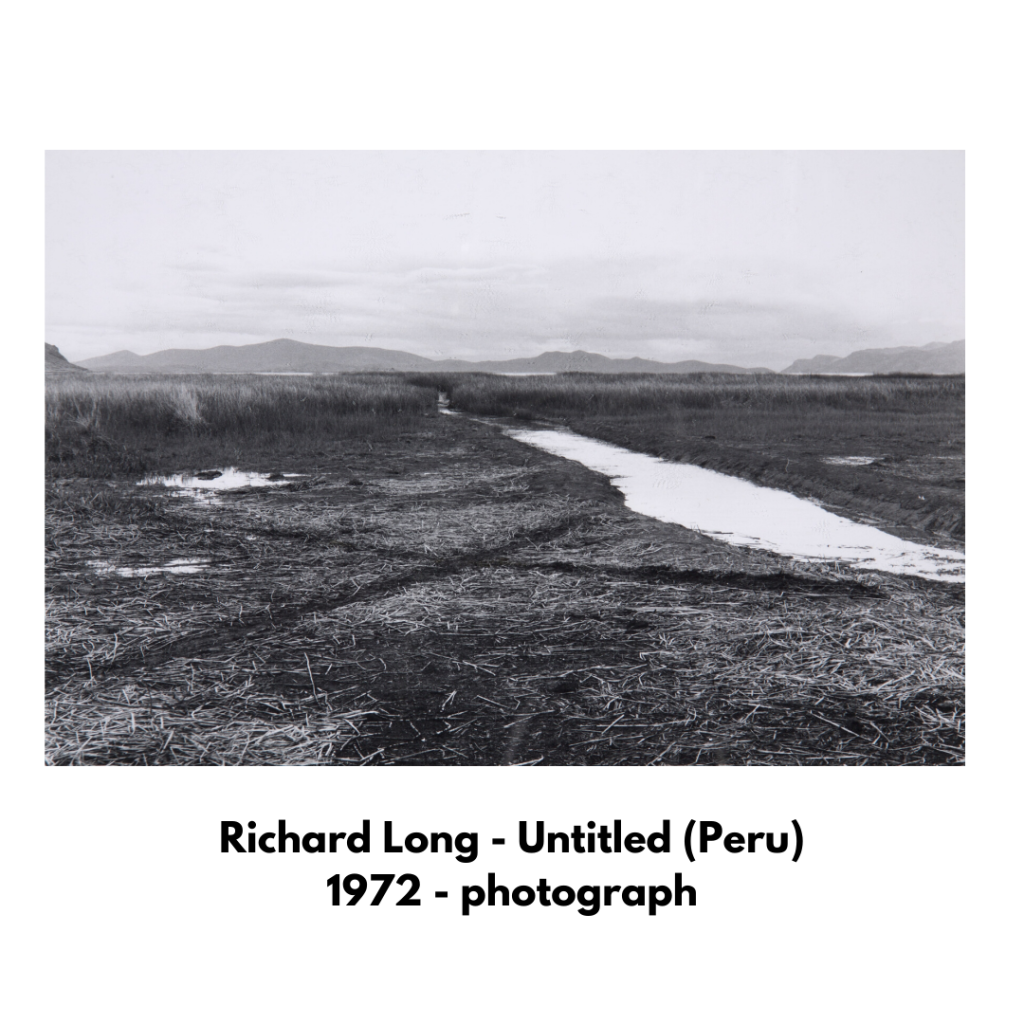

The 20th Century has seen our definition of landscape expand to include urban and industrial landscapes, and has seen artists like Richard Long, who features in the Swindon Collection, use innovative new methods to create artworks directly in the landscape. Many contemporary artists now use video, photography and public art to explore our relationship with place. Arguably, in the midst of the climate crisis, art that considers our relationship with landscape has never been more vital.

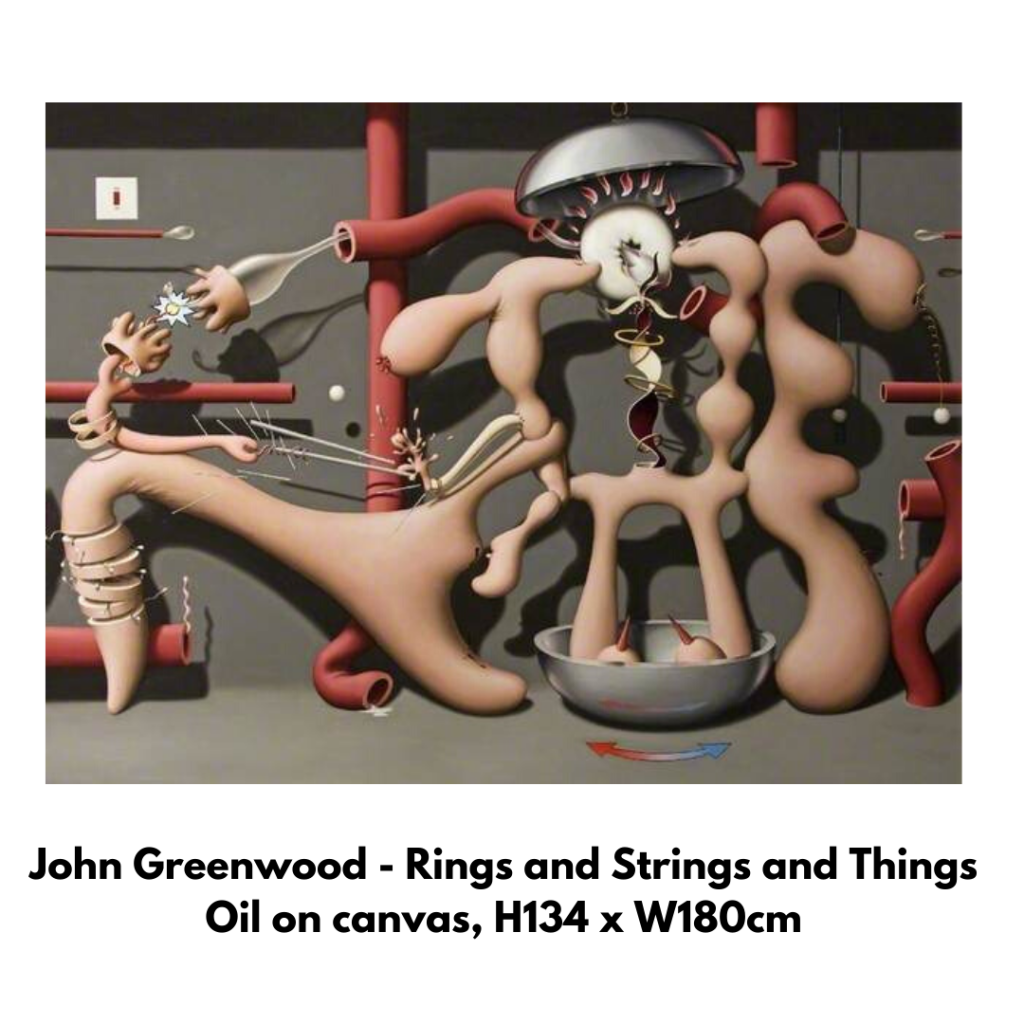

SURREALISM/FANTASY

SWINDON SCENES

DYSTOPIAN WORLDS

PORTRAITURE

THE SEA:

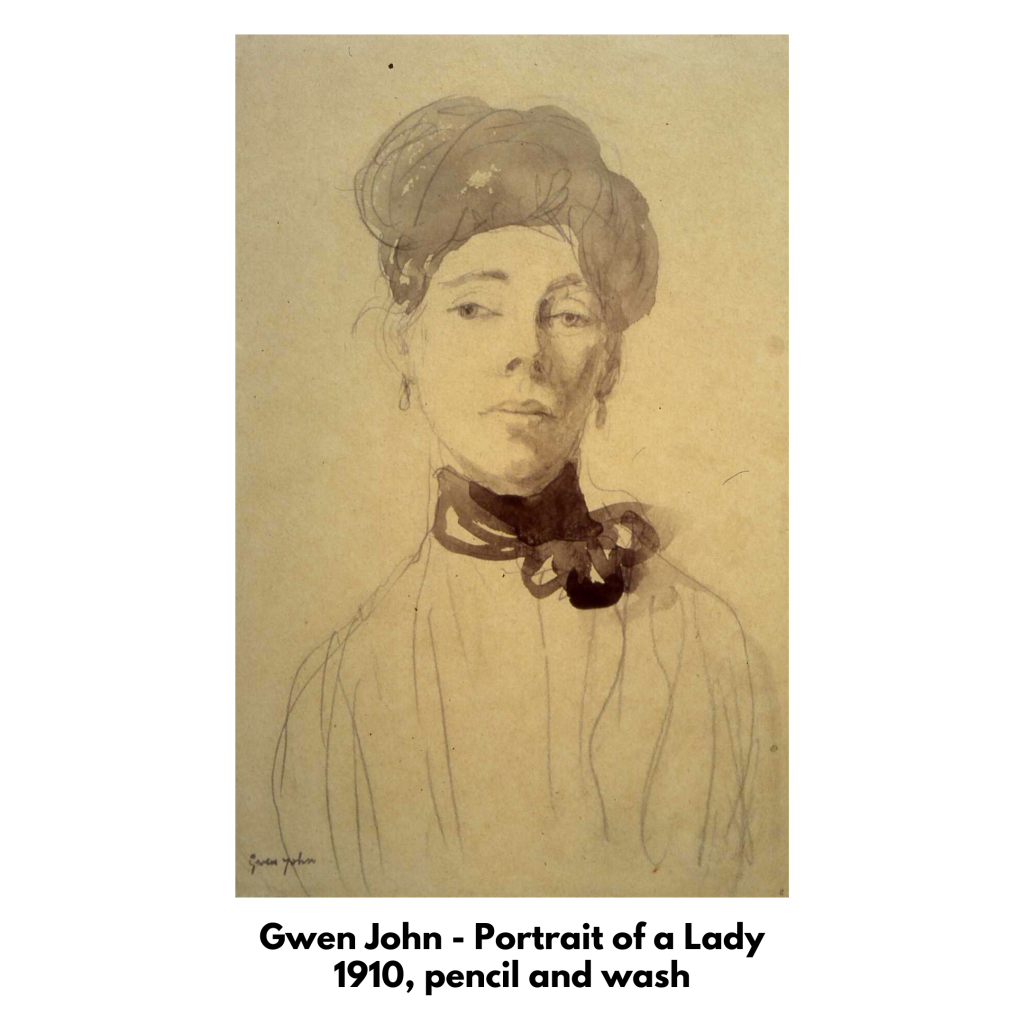

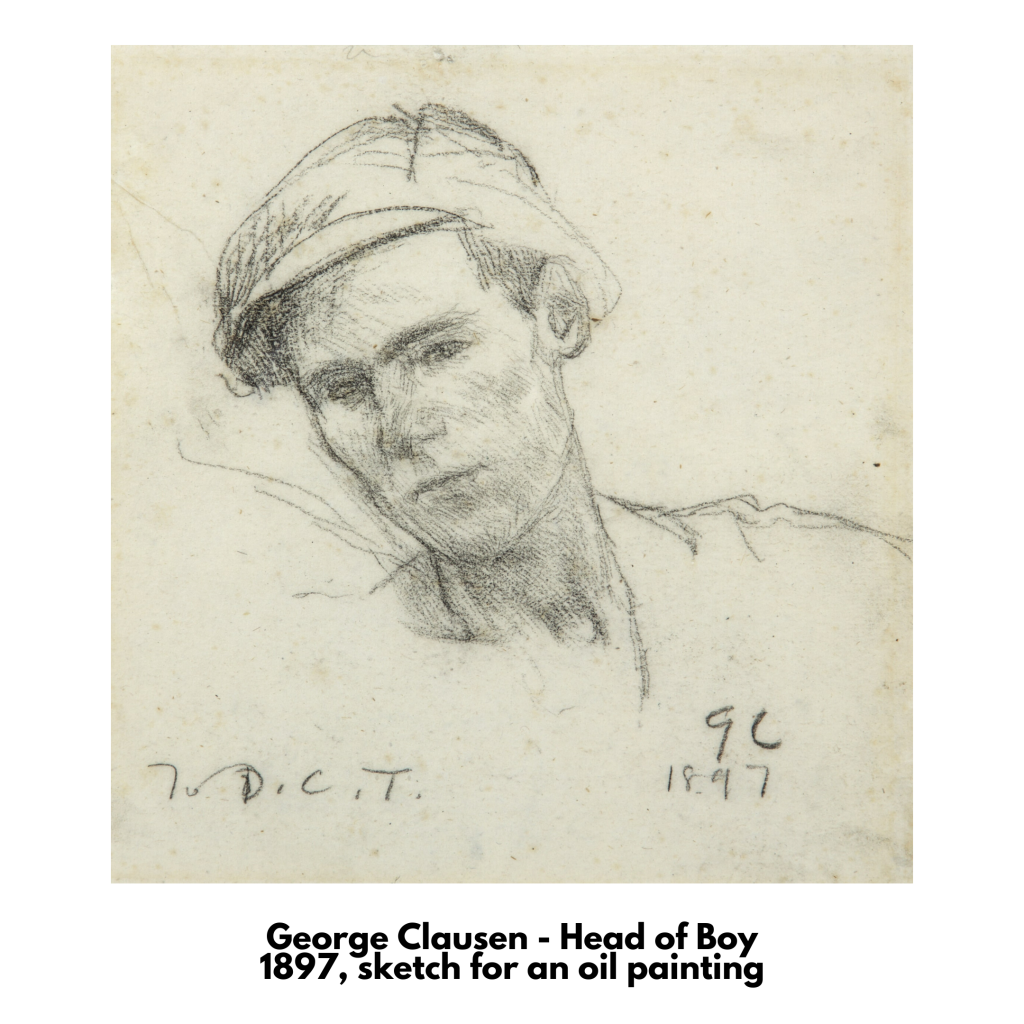

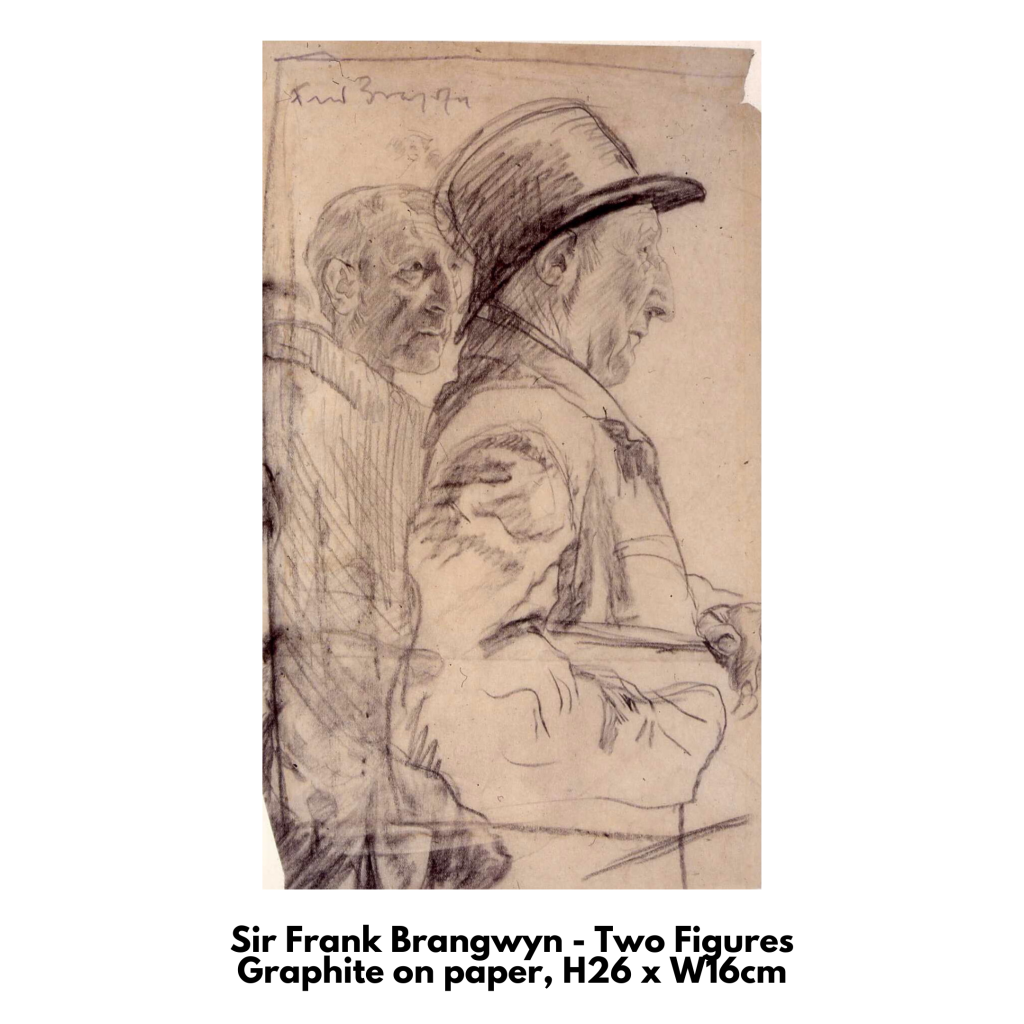

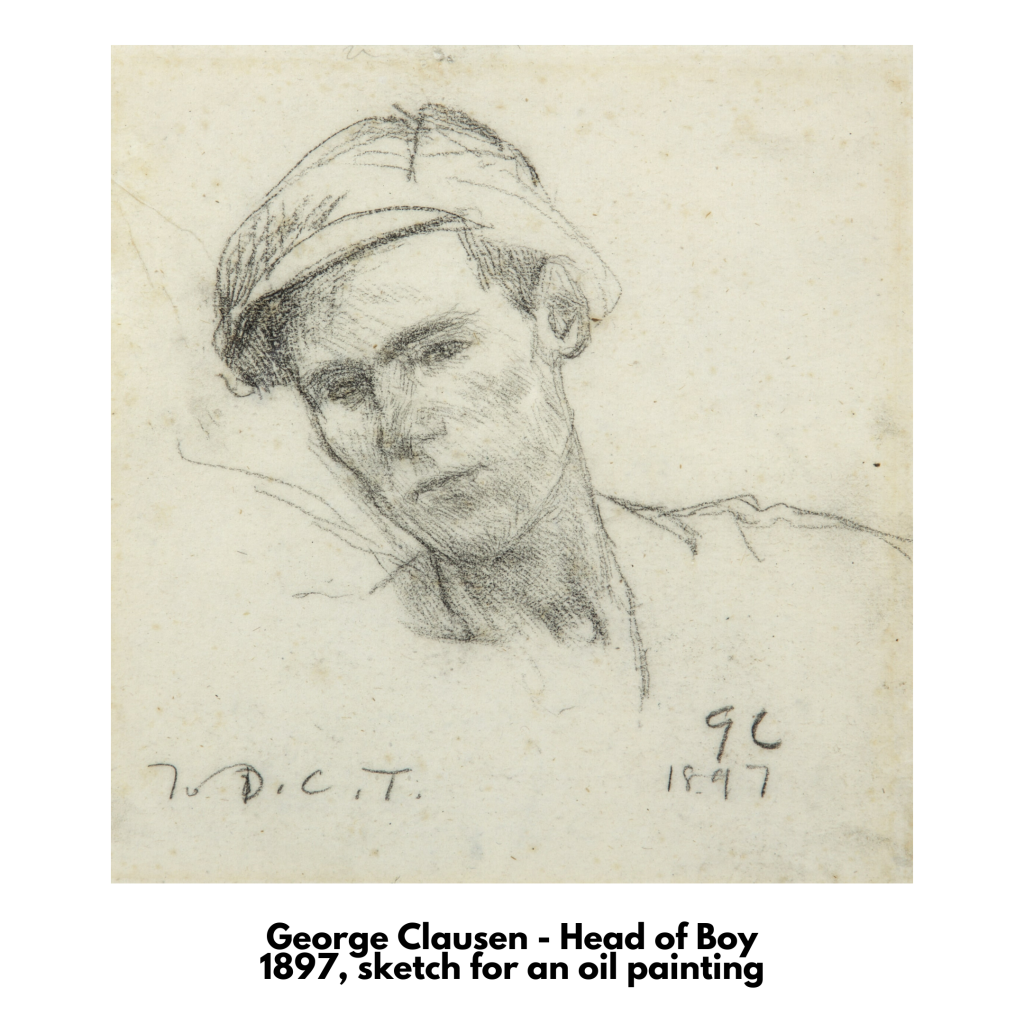

DRAWING:

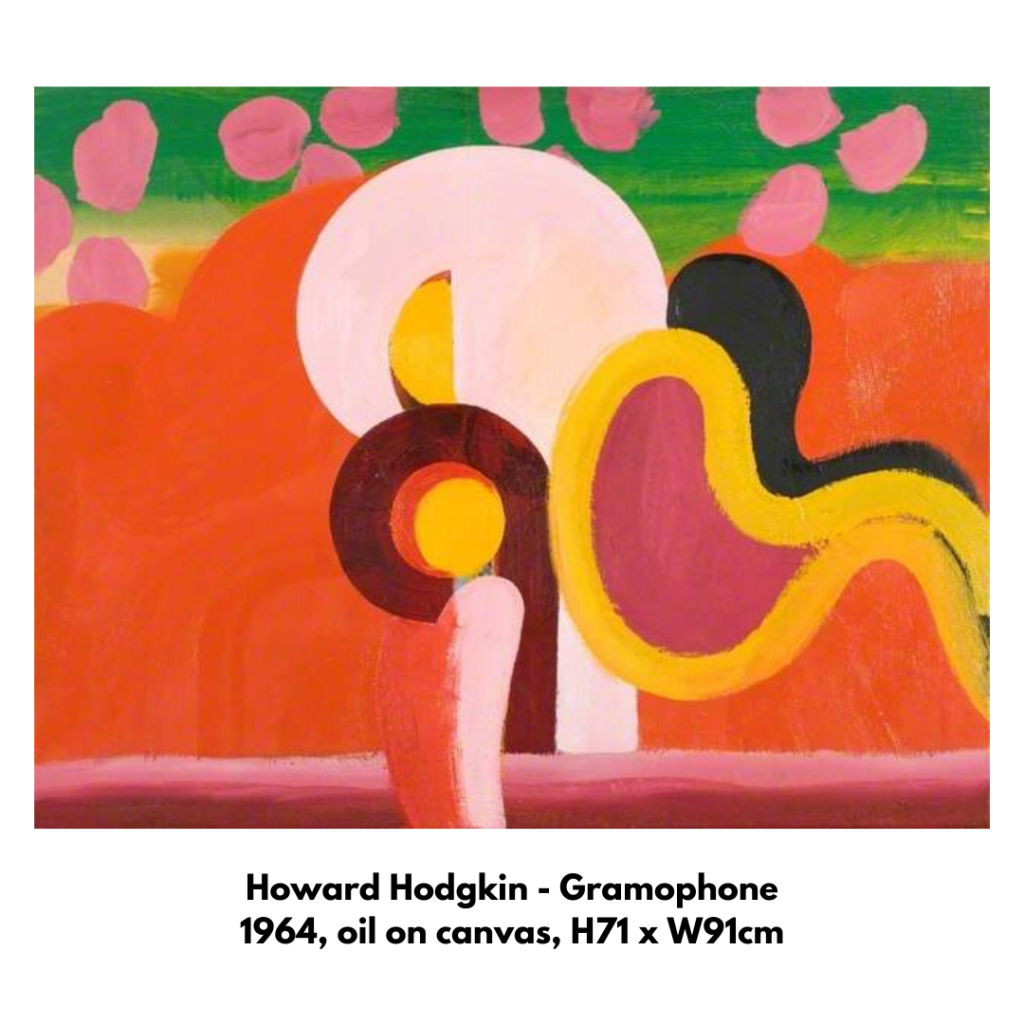

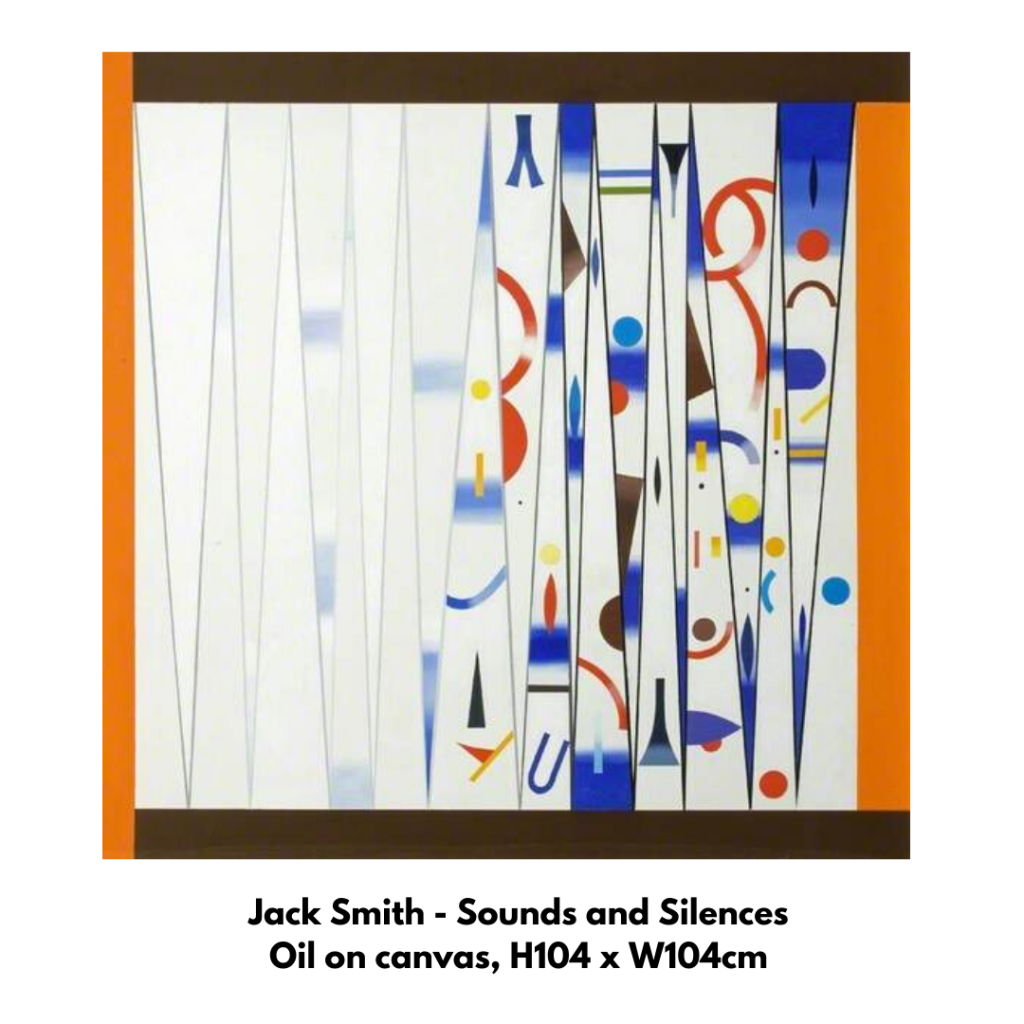

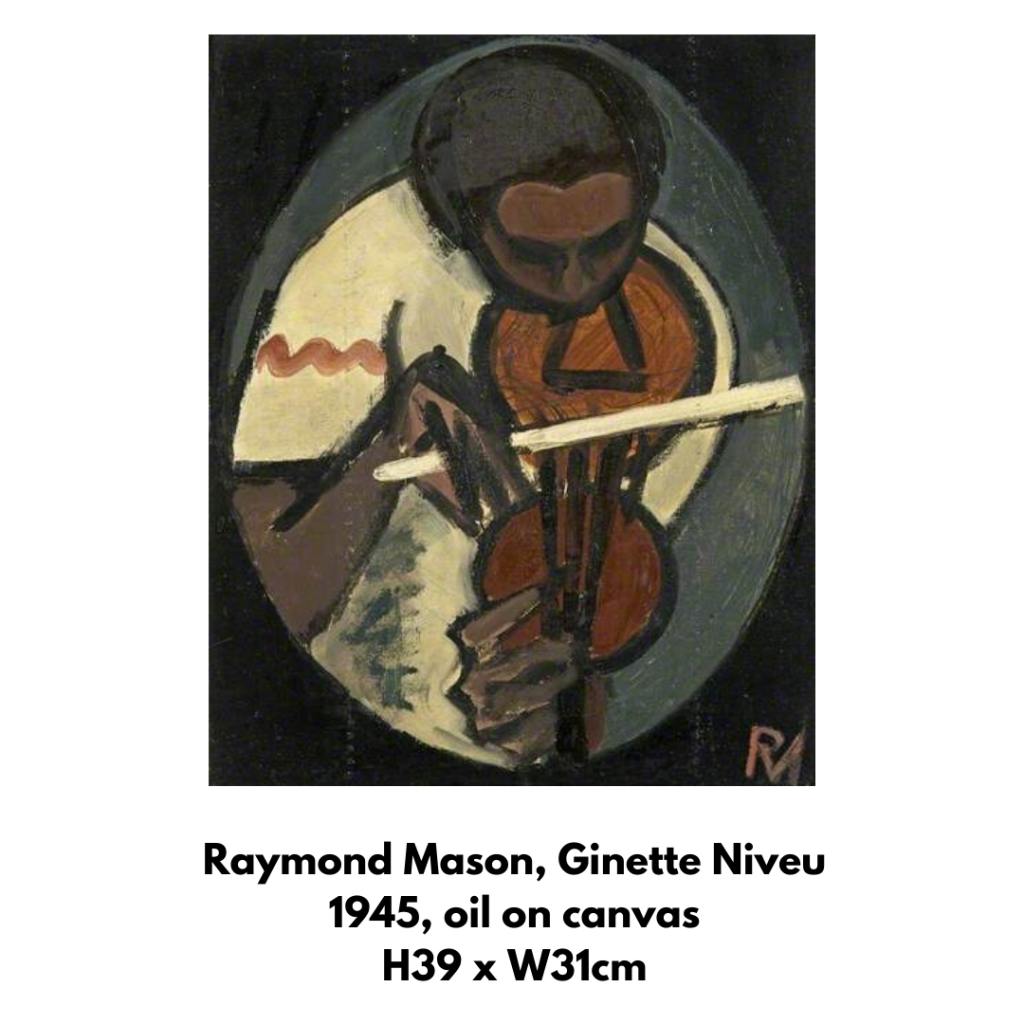

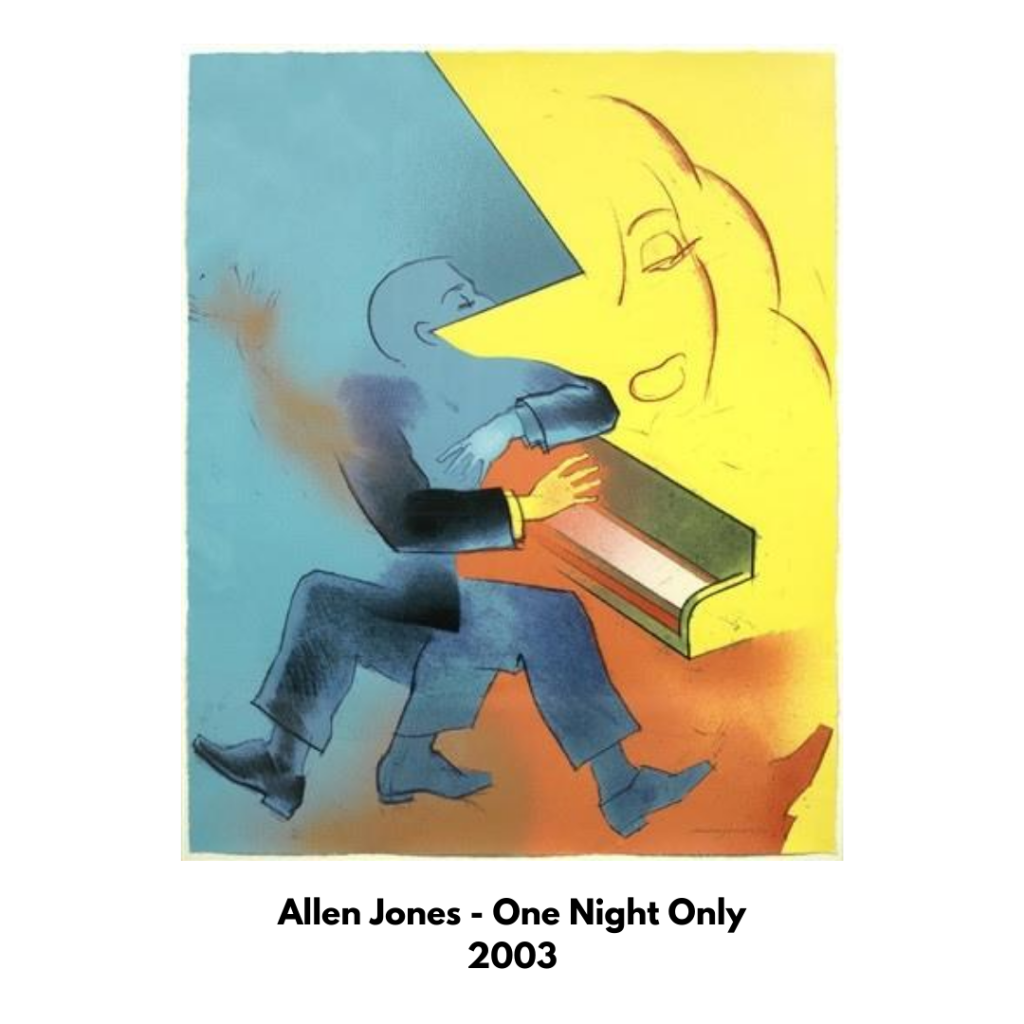

MUSIC AND SOUND: